Minneapolis mother Amy Coughlin accuses Derek Chauvin of constricting her then-12-year-old, autistic child’s breathing during an arrest in January 2017. This is a photograph of her and the child, years later.

Listen to the full episode on Apple, Spotify or wherever else you get your podcasts, and subscribe!

On the night of Jan. 16, 2017, a Minneapolis mother’s then-12-year-old child lapsed into a mental health crisis that left her and family feeling unsafe. She placed an emergency call, seeking help.

Instead, she says, she got Derek Chauvin.

“I felt afraid for my life, and certainly for my kid’s life at that moment, because of the way that [Chauvin] was responding to my words,” the mother, Amy Coughlin, told Law&Crime exclusively on the latest episode of the podcast “Objections: With Adam Klasfeld.”

Revealed on the anniversary of George Floyd’s death, Chauvin’s brush with Coughlin and her child fell months before the officer allegedly brutalized another teenager, whose case formed the basis of a separate civil rights prosecution of the now-convicted murderer.

Like Floyd, the 14-year-old in the federal case allegedly could not breathe because Chauvin put him in the prone position in September 2017.

Coughlin claims that same thing happened to her 12-year-old, mere months earlier.

“He had placed his knee on his back and close to his neck, if not on his neck,” Coughlin said in the interview. “At that point, my child was just screaming ‘Mom,’ screaming. And I was pleading, ‘Please. He’s sick. Please. He’s not resisting. You’re hurting him. Please, get off of him. Please, let him up.'”

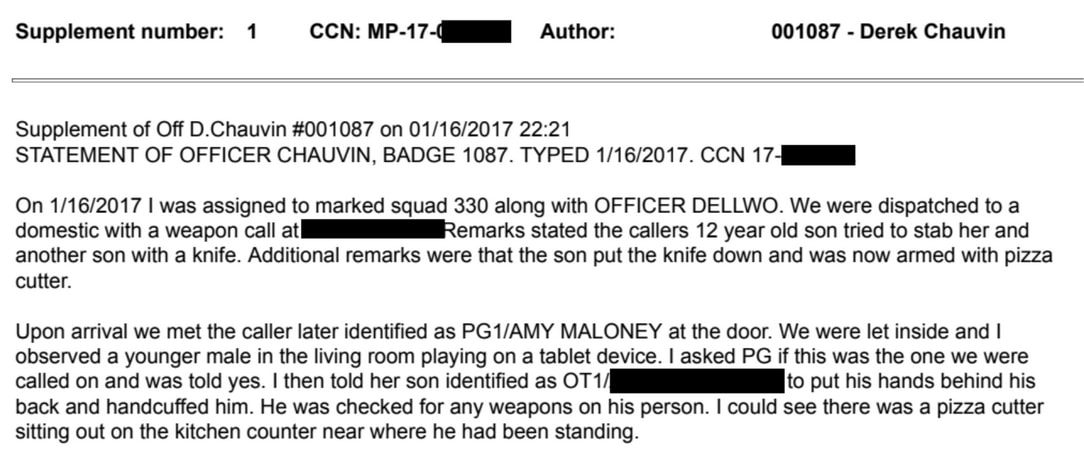

More than four years after the encounter, Coughlin breaks her silence on the “Objections” podcast, and she now has more than her memory to back up her account. She obtained a Minneapolis police report, written by Chauvin, which she shared with Law&Crime.

Coughlin never reported the incident to local, state or federal authorities, but she has been recovering whatever records exist since viewing the viral footage of Floyd’s murder.

“As soon as I’m telling this, I immediately flashed to seeing the video of George Floyd,” Coughlin said. “And as soon as I saw Derek Chauvin, I immediately recognized him from this time, and I knew that was the same officer.”

The Minneapolis Police Department declined to comment on this story, citing the ongoing Department of Justice investigation into their practices. The Minnesota Attorney General’s office and the Justice Department also declined to comment. Chauvin’s lawyer did not respond to a request for comment.

“That Sent Red Flags”

Years after the encounter with Chauvin, the child came out as gender non-binary, adopted a different name, and identified by “they” and “them” pronouns. Law&Crime agreed to withhold their name out of respect for the family’s privacy.

In hours of conversation about the brush with Chauvin, Coughlin speaks about the child the way she remembered them at the time, and the mother says that neither she nor Chauvin were aware of what she would later learn about her child’s gender identity.

As far as Chauvin appears to have known on the day of the incident—and police records written by him reflect this—the officer had been responding to a call by a mother asking for help after the child she then knew as her son had threatened her with a knife.

Acknowledging that the call she placed was alarming, Coughlin says that Chauvin needlessly escalated the situation after the danger had subsided and ignored her pleas to stop. Chauvin’s police report shows the child had been “playing on a tablet device” when the officers entered.

This is the police report Derek Chauvin wrote about the interaction, which Law&Crime redacted to protect the family’s privacy. It reflects the name the mother went by at the time: Amy Coughlin Maloney.

Coughlin shared her story at the time to her partner Alan Harper, who also agreed to be interviewed about what he was told about the encounter.

“Her exact words were, ‘He body-slammed him and then knelt on his neck,” Harper said in a phone interview.

Harper recalled being struck by how out of character it was to hear Coughlin sound so frightened.

“The thing about Amy, she’s a fireball, and for her to admit that Chauvin’s stare and him telling her ‘This is the way it is’ stopped her in her tracks for her baby?” Harper added. “That sent red flags because I’m 6-[foot]-4, 250 pounds, and I’m scared of Amy.”

Chauvin’s immediately hands-on approach stood out to both Coughlin and Harper for another reason.

“Autistic people, kids don’t like to be touched,” Harper noted.

Behavioral Health and Policing

The story of Coughlin and her family falls amid a national conversation about police responses to mental health crises, a topic that was the subject of a recent Senate Judiciary Committee hearing that coincidentally came to pass two days after Chauvin’s verdict.

During those proceedings, Baltimore Police Major Martin Bartness testified and rattled off alarming statistics about mental health and policing.

“We have come together, in large measure, because for at least the past decade, law enforcement actions have led to the annual death of about 1,100 people nationwide,” Bartness told lawmakers, during a hearing titled “Behavioral Health and Policing: Interactions and Solutions.” “The non-profit Treatment Advocacy Center estimates that 25% to 50% of these deaths involve persons who have been diagnosed with a severe mental illness.”

Chauvin’s report notes the child has a “variety of mental health issues” and was subsequently sent to a mental health facility for juveniles.

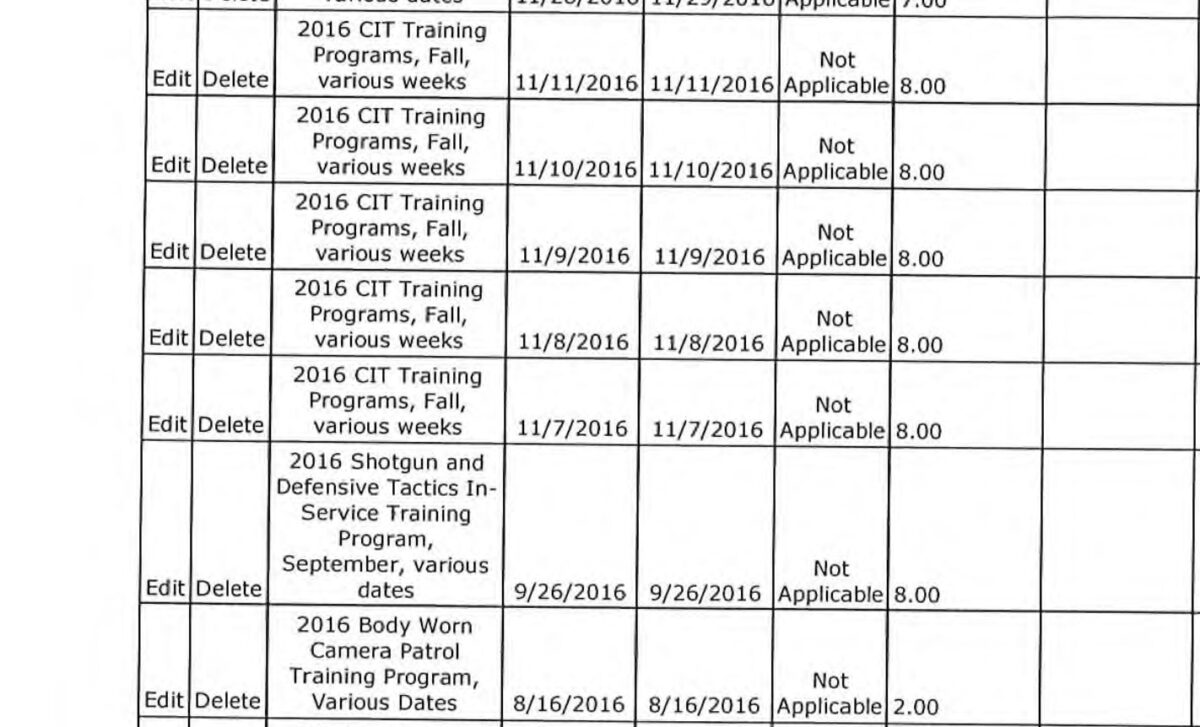

In theory, Chauvin should have responded to Coughlin’s house freshly educated for the interaction. His personnel file shows that Chauvin took at least five “CIT Training Program” sessions—short for “crisis intervention training” for mental health crisis situations—in November 2016.

Derek Chauvin’s personnel file shows that he received several sessions in crisis intervention and body-worn camera training months before the interaction with the 12-year-old.

If Chauvin learned anything during those sessions, Coughlin said, she did not see evidence of that. She said that Minneapolis police long knew about her children’s autism because she often sought their assistance with one of its manifestations: “absconding or elopement,” the tendency of the children to wander and run away.

“So one of the things I did was create flyers that we posted in some of the areas around,” Coughlin wrote. “We live near a kind of a local hot dog joint where a lot of Minneapolis police officers used to hang out. I’m not sure if they do so much anymore. So we posted there and so we knew some of the individuals that way.”

Coughlin recounted that the responses to these incidents would range depending upon the “spirit and the heart” of the officers who responded, but she added that in her many interactions with Minneapolis authorities, she experienced “nothing like” the night with Chauvin.

Chauvin’s personnel file also showed he learned how to use body-worn cameras on Aug. 16, 2016.

Despite this training, the Minneapolis Police Department sent a short denial when Coughlin requested the videos of Chauvin and his then-assisting officer Paul Dellwo from the night of the incident.

“There is no BWC video available for your request,” the department wrote in a May 12th email, abbreviating body-worn cameras. “Your request is now closed. No data found.”

The department did not comment by press time on whether the tapes ever existed, and if so, why they were not preserved.

“Some Shared Experience There”

Bystander video of Floyd’s murder animated the Black Lives Matter movement, spurred the release of other footage, and set in motion the cascade of events leading to Chauvin’s conviction on April 20. Indeed, prosecutors’ closing pitch to jurors exhorted them: “Believe your eyes.”

The second indictment charges Chauvin with violating the rights of a 14-year-old, whom the officer allegedly hit over the head with a flashlight. That case may not have been possible if not for bodycam footage, described by prosecutors in brutal filings made public last November.

“Chauvin hit the child with his flashlight, just eight seconds after first grabbing the child,” Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison’s office wrote last year on Nov. 16. “Two seconds later, Chauvin grabbed the child’s throat and hit him again in the head with his flashlight. The child cried out that they were hurting him, and to stop, and called out ‘mom.'”

Coughlin recalls reading about this and thinking about the parallels: In that incident, Chauvin also allegedly responded to a call from the mother reporting her child’s assault, before the mother protested the kid’s treatment by the person sent to help. Both children were playing with devices before the encounter: the 14-year-old, a phone, and Coughlin’s child, a tablet.

Turning to Facebook, Coughlin asked in a post last month: “How many other acts weren’t officially noted—not to mention, not acted upon?”

Chauvin’s record registered 17 public complaints against him, but Coughlin’s went unreported, partly because of civil unrest in her neighborhood in Minneapolis’s third precinct.

“The whole neighborhood was going up in flames,” Harper, her partner, said. “We were watching, and we were terrified. We didn’t need any more problems, more problems than was going on. We were terrified. So, I talked to her. I said, ‘Do you think we ought to say something or whatever?’ And she said, ‘You know, I don’t think it’s going to do any good.’”

Coughlin recounted feeling “incredible guilt” about staying silent.

“I should have made a report, and I didn’t,” she said, visibly emotional. “It’s kind of like I took it as one of many difficult things that we’ve been through with sort of dealing with systems.”

Over the past than four years, Coughlin said, she did not report the matter for fear of retaliation and other challenges dealing with systems meant to serve her special needs children. She said that she started considering going public after seeing the Floyd video, learning about the Chauvin’s encounter with the other teenager, and finding the so-called “blue card” Chauvin gave her that day—in his handwriting.

“This whole year since Mr. Floyd passed, I have continually thought back on it and thought: There is some shared experience there, and it’s just haunting,” she said.

Coughlin also acknowledged one of the key differences: She and her children are white.

“Is that why I still have the honor of my child being here?” Coughlin asked, referring to the child’s race. “I don’t know.”

“I Survived Derek Chauvin”

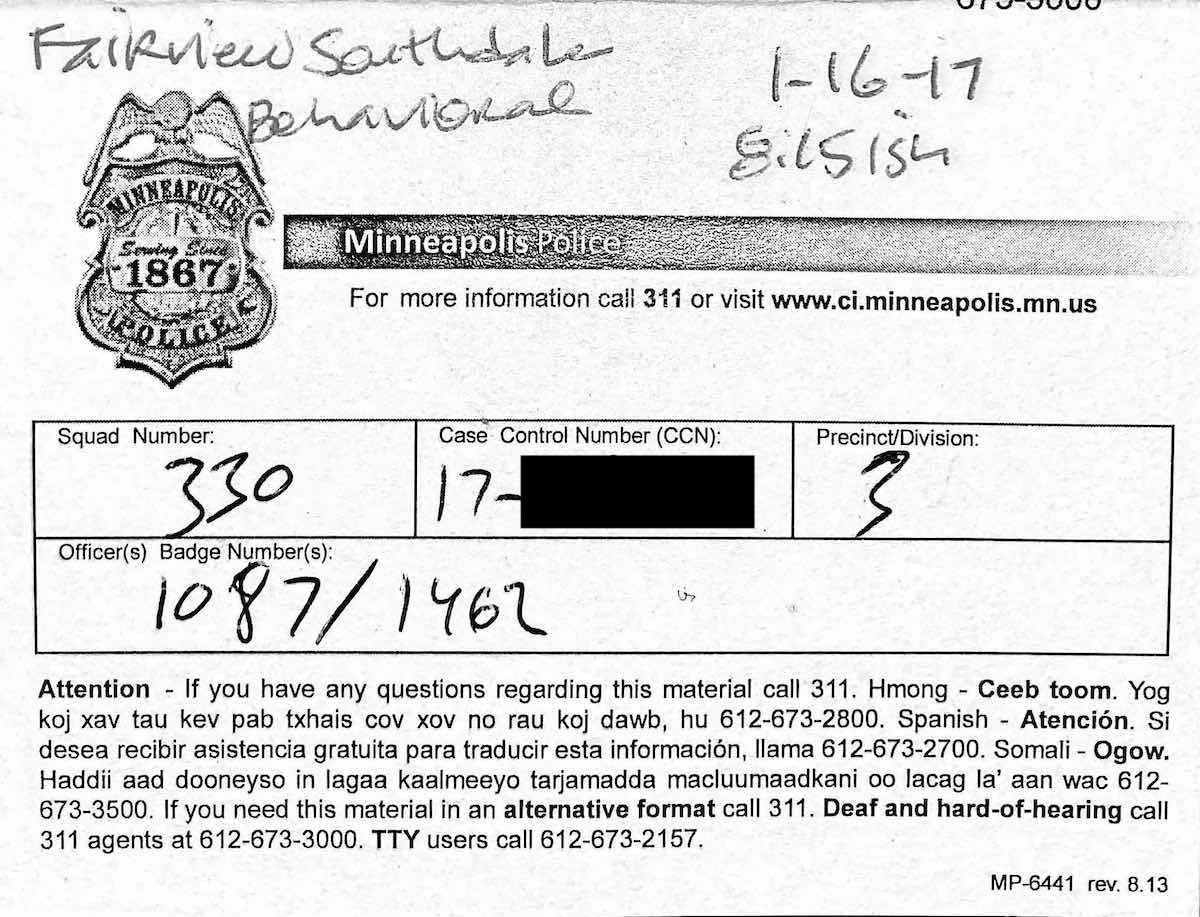

Under the department’s policy, Minneapolis policy must hand out blue cards with information about social services to anyone who reports a crime, and records show that Chauvin followed this protocol. Coughlin provided the card that Chauvin gave her to Law&Crime.

This is the blue card Amy Coughlin says Derek Chauvin gave her on the night of the incident.

“So I found the blue card, and it had the squad and the [badge] number,” she recounted. “I just quickly did a Google search, and I went, ‘This is the same.'”

Coughlin said this information allowed her to reconstruct details about the event that she had forgotten, including the date and time.

“We’ve had multiple times when my child needed to go into the hospital,” she noted. “So I just had never pulled those records.”

Asked why she decided to share her story, Coughlin replied: “First and foremost, it’s honoring the Black Lives Matter movement and the racial part of policing that needs to be completely overhauled.”

But Coughlin added she also hopes to draw attention to the other side of criminal justice and police reform, concerning mental health issues.

“I hope anyone who would see our story or hear our story would take from it is that the issues are multidimensional, when it comes to someone who, for example, is struggling with an addiction or struggling in an active mental health crisis,” she said.

“We don’t have procedures and funding, frankly, for what I feel needs to be a much more comprehensive approach,” she added.

Before agreeing to an interview, Coughlin reported seeking her family’s permission for every act of disclosure that might affect their privacy, from the child’s name to a picture of the two of them that she ultimately provided to Law&Crime for publication.

Asked about that conversation with her older child, Coughlin recalled the child telling her: “I survived Derek Chauvin, and I survived a year at residential treatment where I was abused daily. So, we can do this, Mom.”

“That’s pretty much why I’m here, really: to honor both of my children’s resilience,” she added.

Listen to the podcast below:

(Photo used with Coughlin’s permission)