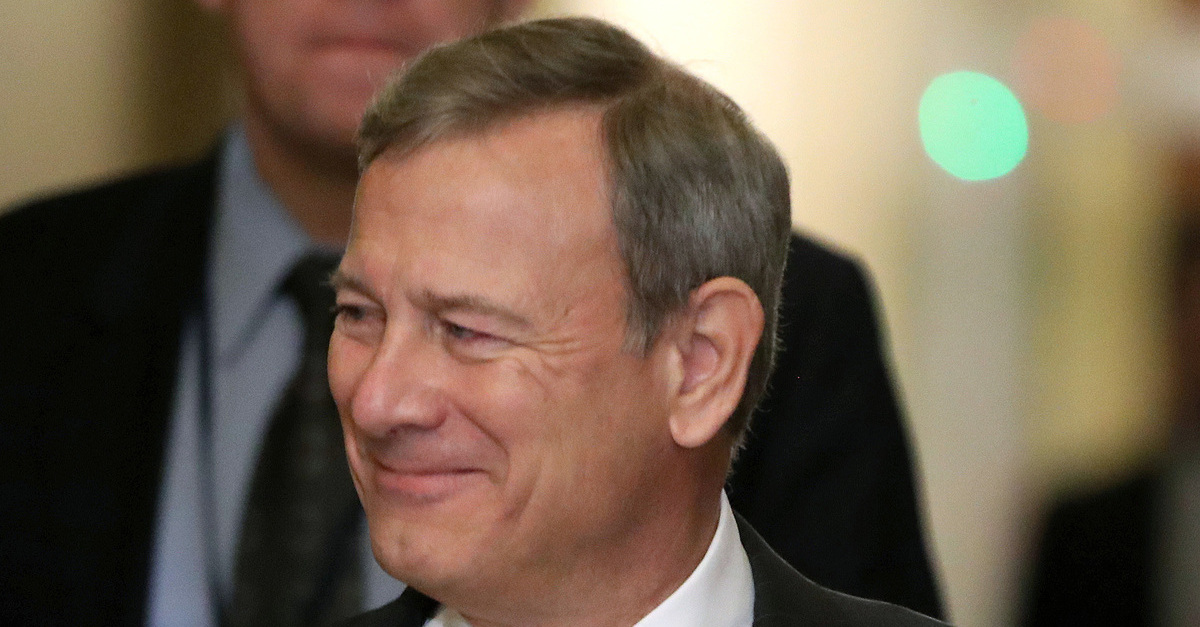

The U.S. Supreme Court on Monday did two unusual things in an opinion, at heart, about religious freedom and the First Amendment. First, in atypical fashion, the nation’s highest court was favorable to a petitioner’s argument that they had standing to sue. Second, the 8-1 decision in Uzuegbunam v. Preczewski marks the very first time Chief Justice John Roberts has ever penned the lone dissent.

The facts of the case center around evangelical Christian Chike Uzuegbunam, a former student at Georgia Gwinnett College, who was repeatedly barred from practicing his religion on campus by multiple levels of authority—including multiple campus police officers and the Director of the Office of Student Integrity.

After learning about the campus’s two, small so-called “free speech zones,” and the school’s policy about using those zones for religious proselytizing, Uzuegbunam obtained the necessary permit and began to exercise his faith in accordance with the rules.

But, again, the school shut him down.

The decision notes:

Twenty minutes after Uzuegbunam began speaking on the day allowed by his permit, another campus police officer again told him to stop, this time saying that people had complained about his speech. Campus policy prohibited using the free speech zone to say anything that “disturbs the peace and/or comfort of person(s).”The officer told Uzuegbunam that his speech violated this policy because it had led to complaints. The officer threatened Uzuegbunam with disciplinary action if he continued. Uzuegbunam again complied with the order to stop speaking.

A second student, Joseph Bradford, “decided not to speak about religion because of these events,” according to the majority opinion by Justice Clarence Thomas.

A member of the University System of Georgia, the college is a public university which means that Uzuegbunam’s First Amendment claims would have certainly been reviewable by a federal court.

Perhaps sensing a loss, however, the school quickly changed their policies after being sued—for an injunction blocking the policy and for nominal damages—and said the students’ claims were moot.

“The students agreed that injunctive relief was no longer available, but they disagreed that the case was moot,” the opinion explains. “They contended that their case was still live because they had also sought nominal damages.”

The school won at both the district and appellate level on the notion that a request for nominal damages is not enough, on its own, to sustain a case that would otherwise fail for being moot. Specifically, the appeals court said that if the students had, for example, requested (and failed to prove) compensatory damages as well, then nominal damages claim would have kept their claim alive.

Nominal damages are a form of declaratory relief which essentially says the person filing a lawsuit has won their case on the merits because the other party broke the law. Compensatory damages are a form of relief which are directly tied to the harm the plaintiff suffered as a result of the defendant’s law-breaking.

The nation’s high court has, for decades, been on a more or less consistent path of removing the standing to sue—especially when it comes to government officials. This has been one of the long-term projects for the conservative judicial movement’s reaction to the liberal jurisprudence of the mid-twentieth century. Court watchers and commentators generally expect the nine justices to carve away standing claims whenever they have a chance. But that didn’t happen, for one reason or another, in Uzuegbunam‘s case.

University of Texas Law Professor Steve Vladeck noted the unusual nature of Monday’s opinion viz. standing concerns:

This decision is important for what it does *not* do. There had been real concern among a number of practitioners and scholars that #SCOTUS was going to make it harder to bring civil suits with little (if any) economic damages, but the Court today reaffirmed that that’s okay.

— Steve Vladeck (@steve_vladeck) March 8, 2021

The high court’s logic was fairly lucid here—and a complete repudiation of the test used by the lower courts.

The lower courts said the students needed to pin their nominal damages claim on the idea that they had been economically harmed. They didn’t make the claim that infringing on their First Amendment right to freedom of religion was a monetary issue, so, the lower courts said, they couldn’t make the claim for the legal equivalent of a moral victory here.

Eight justices said that makes no sense at all.

Again, the opinion at length:

We hold only that, for the purpose of Article III standing, nominal damages provide the necessary redress for a completed violation of a legal right.

Applying this principle here is straightforward. For purposes of this appeal, it is undisputed that Uzuegbunam ex-perienced a completed violation of his constitutional rights when respondents enforced their speech policies against him. Because “every violation [of a right] imports damage,” nominal damages can redress Uzuegbunam’s injury even if he cannot or chooses not to quantify that harm in economic terms.

Roberts, for his part, framed his dissent as something of an allegiance to tradition and keeping federal court dockets limited and efficient.

“If nominal damages can preserve a live controversy, then federal courts will be required to give advisory opinions whenever a plaintiff tacks on a request for a dollar,” the chief justice opined. “Because I would place a higher value on Article III, I respectfully dissent.”

His reasoning is elaborated later on:

Today’s decision risks a major expansion of the judicial role. Until now, we have said that federal courts can review the legality of policies and actions only as a necessary incident to resolving real disputes. Going forward, the Judiciary will be required to perform this function whenever a plaintiff asks for a dollar. For those who want to know if their rights have been violated, the least dangerous branch will become the least expensive source of legal advice.

“Perhaps defendants will wise up and moot such claims by paying a dollar, but it is difficult to see that outcome as a victory for Article III,” Roberts goes on. “Rather than encourage litigants to fight over farthing.”

According to The Supreme Court Database maintained by Washington University Law, which has record up until 2019, Roberts has never been the sole dissenter in a case. Legal Twitter was rife with speculation about whether or not Roberts had ever done so after the fact—heavily leaning towards a “No.”

The National Law Journal later confirmed that Uzuegbunam was indeed Roberts’ first solo dissent.

[image via Jim Lo Scalzo-Pool/Getty Images]