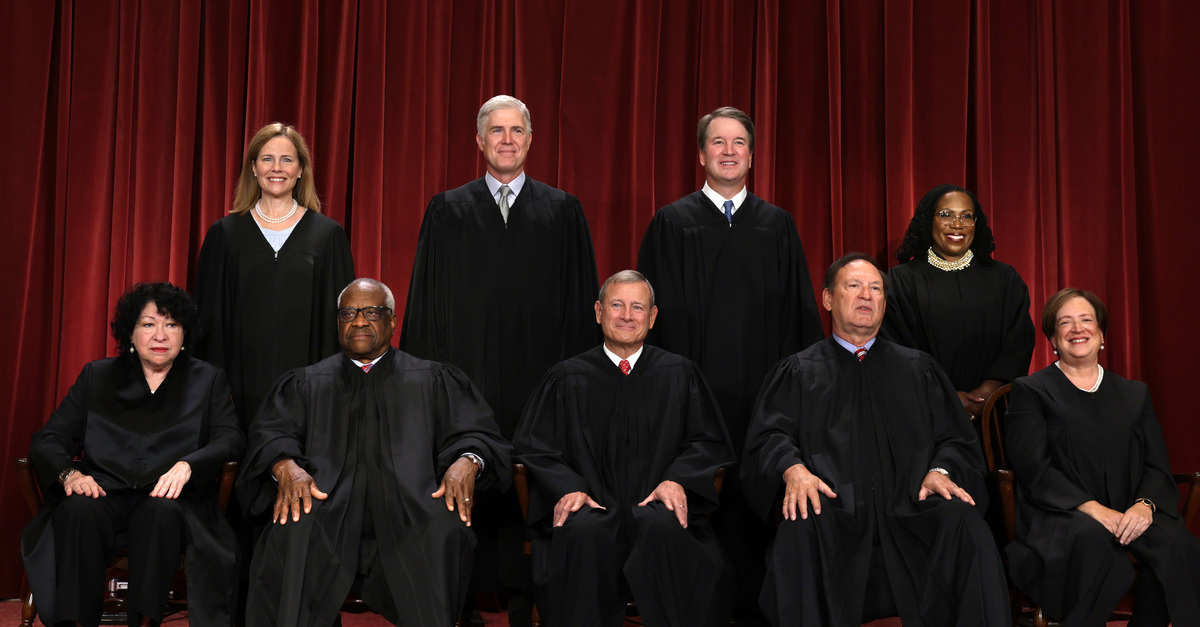

United States Supreme Court (front row L-R) Associate Justice Sonia Sotomayor, Associate Justice Clarence Thomas, Chief Justice of the United States John Roberts, Associate Justice Samuel Alito, and Associate Justice Elena Kagan, (back row L-R) Associate Justice Amy Coney Barrett, Associate Justice Neil Gorsuch, Associate Justice Brett Kavanaugh and Associate Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson.

The Supreme Court heard three hours of oral arguments Wednesday in an important case about whether state courts have any power over federal elections. Moore v. Harper asks the justices to test the “independent state legislature theory” – the concept that under the Constitution, only state legislatures have the power to regulate federal elections, and that state courts may not interfere.

North Carolina has a long history of having its gerrymandered districting plans struck down by state and federal courts. In the current case before the justices, North Carolina’s GOP-controlled General Assembly sued the Tarheel State’s Supreme Court for ruling against its congressional maps that had been gerrymandered to benefit Republican Party candidates.

The state court ruled 4-3 in February 2022 that Republican legislators had been “discriminating against certain voters by depriving them of substantially equal voting power.”

The state legislature, however, effectively ignored the state supreme court’s decision and instituted a second — still gerrymandered — map. The court parried by ordering a special master to create new maps that would be used in the 2022 elections.

Republican legislators, led by speaker of the North Carolina house Rep. Tim Moore, now argue that state’s highest court exceeded the scope of its authority to regulate federal elections under the U.S. Constitution’s Elections Clause.

North Carolina’s Democratic governor and attorney general say that Moore’s elections clause argument is “extreme and dangerous,” and that the Republican attempt to evade judicial review is an unprecedented power-grab.

Election law experts say the importance of the case cannot be overstated. Vox‘s Ian Millhiser characterized the case as “potentially the biggest threat to free and fair elections in the United States to reach the Supreme Court in my lifetime,” and predicts hat unless one conservative justice “has second thoughts, the future of US elections will be decided by Trump-appointed Justice Amy Coney Barrett.”

A profound statement of the case’s significance came from Justice Elena Kagan herself, about an hour into Wednesday’s arguments. Kagan called the Republican-petitioners’ argument “a theory with big consequences,” and explained why:

[A ruling in favor of Moore] would say that if a legislature engages in the most extreme forms of gerrymandering, there is no state constitutional remedy for that, even if the courts think that’s a violation of the Constitution. It says legislatures can enact all manner of restrictions on voting, get rid of all kinds of of voter protections [including] what the state constitution in fact prohibits. It might allow sates legislatures to give themselves a role in the certification of elections and the way election results are calculated. And in all these ways, I think what might strike a person is that this is a proposal that gets rid of the normal checks and balances on the way big governmental decisions are made in this country. You might think that it gets rid of those checks and balance at exactly the time the time when they are needed most. Legislators will do what it takes to get reelected. There are countless tines when they have incentives to suppress votes, to negate votes, to dilute votes, and to prevent voters from having true access and true opportunity engage the political process.

The Elections Clause says, “the Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof.” Although it has not been a central part of a direct SCOTUS-ruling, it was mentioned in 2000 by then-Chief Justice William Rehnquist in his concurrence to Bush v. Gore as a means by which to limit state court authority to change federal elections rules. Rehnquist’s concurrence was joined by the late Justice Antonin Scalia and by Justice Clarence Thomas, the senior justice who presided over Wednesday’s arguments.

In 2017, Thomas sided with the Court’s liberal wing in a 5-3 ruling against North Carolina’s gerrymandered redistricting map. In the 2017 case, Justice Samuel Alito dissented (along with Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Anthony Kennedy) and said, “Partisan gerrymandering dates back to the founding, and while some might find it distasteful, ‘[o]ur prior decisions have made clear that a jurisdiction may engage in constitutional political gerrymandering, even if it so happens that the most loyal Democrats happen to be black Democrats and even if the State were conscious of that fact.'”

Attorney David H. Thompson took the podium to make the argument some have characterized as “deranged” and “nonsensical” on behalf of Moore. Thompson immediately pointed to history, mentioning Alexander Hamilton, Philip Schuyler, and Federalist 78.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor questioned the veracity of whether founding history really supports Thompson’s position, and noted that the Tenth Amendment reserves for the states all powers that are not specifically delegated otherwise.

Sotomayor commented, “if there’s no substantive limitation in the Elections Clause, I don’t know how we could read one in.”

When Thompson responded with his version of the history of the founding era, the two entered into a tense exchange:

Sotomayor: There were only 13 colonies. If six of them weren’t doing something, that’s a fairly substantial majority.

Thompson: I’m going to knock them all down. It’ll be 12 to one once I’m done.

Sotomayor: Yes if you rewrite history it’s very easy to do.

Kagan took a similar posture, and dispensed with Thompson’s precedent-based response with a terse, “If you’re going to quote one at me, I’m going to quote three at you.”

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson repeatedly asked Thompson how it would be possible to “cut a state constitution out of the equation when it is giving the state legislative the authority to exercise legislative power.”

Justice Brett Kavanaugh asked Thompson whether his advocacy of the independent legislature theory goes farther in this case than Rehnquist did in the Bush v. Gore concurrence. The comment was significant in that Kavanaugh, a member of George W. Bush’s legal team, specifically supported the theory in 2000.

Justice Neil Gorsuch raised a concern that would come up many times during the three hours of oral arguments: the litigants may be choosing the proper analytical framework for the case based on “whose ox is being gored.”

Former Acting Solicitor General Neal Katyal began his argument on behalf of the respondents by telling Justice Thomas, “in two decades of arguing before you, I have waited for this precise case, because it speaks to your method of interpretation: that is history.

Katyal called the evidence that the founders would have expected state courts to have the power to review legislative action on elections “overwhelming,” and cautioned that the “blast radius” of the Court’s decision could be dangerously far-reaching.

Thomas raised a concern of his own and asked Katyal, “If the state legislature had been very, very generous to minority voters in their redistricting, and the state supreme court said [that the plan] violated their own state constitution, would you be making the same argument?”

Gorsuch pushed Katyal to defend his argument that history favors his position. The justice opened a line of colloquy with Katyal that devolved into what many court-watchers noticed was uncharacteristically combative. Gorusch characterized Katyal’s argument as one that would support a state’s right to maintain the 3/5 compromise in its own constitution.

Katyal argued that his argument regarding the Elections Clause relates to different language, and carries no such implication. Gorsuch repeatedly interrupted Katyal with similar questions, each of which Katyal responded in the negative. Finally, Gorsuch shot back, “I understand the mantra.”

Attorney Donald Verilli argued a similar position in the case on behalf of the North Carolina state court. In doing so, he pointed out to the justices that the issue of voting rights is so important right now that four states (New York, California, Florida, and Ohio) have amended their constitutions to restrict partisan gerrymandering.

Justice Samuel Alito pressed Verilli on one historical basis of his argument.

“We’ve heard about the English Bill of Rights,” said Alito, “has anybody ever thought that the English Bill of Rights has anything to do with one-person-one-vote, much less political gerrymandering?”

Verilli responded that, in fact, historical roots of the English Bill of Rights do trace back to the idea that manipulation of the electoral process is an important thing to avoid.

Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar argued on behalf of the Biden administration as an amicus curiae supporting the respondents in the case, once again urging SCOTUS not let the independent state legislature theory carry the day.

[Image via Alex Wong/Getty Images]