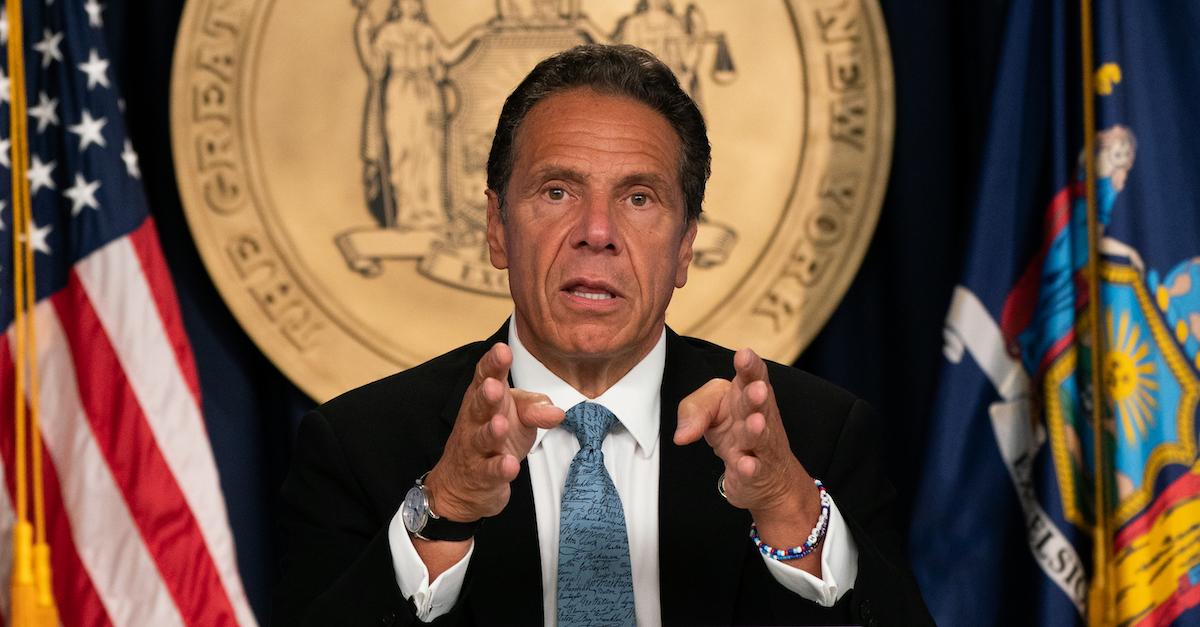

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo

Harvard Law Professor Cass R. Sunstein on New Year’s Day released a 16-page paper which legally juxtaposed the U.S. Supreme Court’s recent smackdown of novel coronavirus restrictions by Gov. Andrew Cuomo (D-N.Y.) against the Court’s 1944 upholding of evacuation orders aimed at Japanese Americans during WWII. The critical distinction, Sunstein argued, was that while the Supreme Court’s 1944 decision in Korematsu v. U.S. was highly deferential to the actions of the executive branch and of the military, the Court’s 2020 decision against Cuomo’s COVID-19 orders was not. And that is important for predicting the way the Court will examine future cases.

Recall that Supreme Court, led by its new conservative majority, ruled 5-4 on Thanksgiving morning that Gov. Cuomo likely violated the First Amendment when he issued executive orders which, among other things, functionally limited the size of various worship gatherings. The Supreme Court’s decision granted a temporary injunction against Cuomo’s orders in favor of both a downstate Roman Catholic diocese and a synagogue. (Cuomo has subsequently racked up another similar loss at the lower appellate level.)

Sunstein posited that the Supreme Court’s decision, Roman Catholic Diocese of Brooklyn v. Cuomo, “can reasonably be seen as a kind of anti-Korematsu – that is, as a strong signal of judicial solicitude for constitutional rights, and of judicial willingness to protect against discrimination, even under emergency circumstances in which life is on the line.”

Korematsu is the Supreme Court’s much-maligned 1944 decision against Japanese Americans. In a paragraph filled with blatantly questionable logical gymnastics, the majority in Korematsu held that the wholesale exclusion of all Japanese Americans from designated areas on the West Coast due to the alleged disloyalties of some Japanese Americans was somehow not racism. The dizzying logic from the majority holding by Justice Hugo Black, an ex-Ku Klux Klan member who eventually ruled to desegregate schools, is as follows:

It is said that we are dealing here with the case of imprisonment of a citizen in a concentration camp solely because of his ancestry, without evidence or inquiry concerning his loyalty and good disposition towards the United States. Our task would be simple, our duty clear, were this a case involving the imprisonment of a loyal citizen in a concentration camp because of racial prejudice. Regardless of the true nature of the assembly and relocation centers — and we deem it unjustifiable to call them concentration camps with all the ugly connotations that term implies — we are dealing specifically with nothing but an exclusion order. To cast this case into outlines of racial prejudice, without reference to the real military dangers which were presented, merely confuses the issue. Korematsu was not excluded from the Military Area because of hostility to him or his race. He was excluded because we are at war with the Japanese Empire, because the properly constituted military authorities feared an invasion of our West Coast and felt constrained to take proper security measures, because they decided that the military urgency of the situation demanded that all citizens of Japanese ancestry be segregated from the West Coast temporarily, and finally, because Congress, reposing its confidence in this time of war in our military leaders — as inevitably it must — determined that they should have the power to do just this. There was evidence of disloyalty on the part of some, the military authorities considered that the need for action was great, and time was short. We cannot — by availing ourselves of the calm perspective of hindsight — now say that at that time these actions were unjustified.

Korematsu has been harshly repudiated but not explicitly overruled by a subsequent case involving President Donald Trump’s travel ban.

Sunstein took time to trash the Korematsu holding “as a national shame” and as “a terrible stain on the United States and the Supreme Court itself.” But Korematsu is important, he explained, because in it, the Supreme Court “for the first time” set forth the framework of strict scrutiny: the formula by which the court harshly examines government infringements upon fundamental rights (e.g., religious liberty, free speech) or suspect classifications (e.g., race). As Sunstein deftly noted, Korematsu kicked off its analysis of Japanese internment as such:

It should be noted, to begin with, that all legal restrictions which curtail the civil rights of a single racial group are immediately suspect. That is not to say that all such restrictions are unconstitutional. It is to say that courts must subject them to the most rigid scrutiny. Pressing public necessity may sometimes justify the existence of such restrictions; racial antagonism never can.

Even though Korematsu came down on the side of the government, not those whose ancestry and genetics resulted in their marginalization and suppression, strict scrutiny endured to the present day. Korematsu held that the “pressing public necessity” of World War II overrode the individual claims of a man penalized for violating the government’s exclusion orders and—shockingly—found that the government somehow hurdled over the legal principle which is generally insurmountable.

Sunstein’s paper sought to question whether the anti-Cuomo, pro-religious-freedom decision in Roman Catholic Diocese was “genuinely generalizable as an anti-Korematsu, or whether it is best seen as a distinctive product of the contemporary Court’s particular solicitude for religion and religious institutions.”

He concluded that the decision was distinctly and definitively anti-Korematsu:

[B]ecause of the serious health effects of the pandemic, and because of the plausibility of a plea for judicial respect for complex choices by elected officials, Roman Catholic Diocese can reasonably be seen as a kind of anti-Korematsu — that is, as a strong signal of judicial solicitude for constitutional rights, and of judicial willingness to protect against discrimination, even under emergency circumstances in which life is on the line.

Broadly speaking, Sunstein asserts that it “should not be controversial” that the Roman Catholic Diocese court ruled that restrictions against the plaintiff churches were unconstitutional if similar restrictions are not placed against “institutions that are relevantly similar.” However, he says it is far more controversial that the Supreme Court gave Gov. Cuomo’s administration “very little deference.” Commenting further on court’s approach to Roman Catholic Diocese, Sunstein said that “the Court’s reasoning can be taken to be a strong signal that whenever some businesses or other institutions are exempted as ‘essential,’ a failure to exempt houses of worship will run into serious trouble.”

In other words, when the government takes actions against protected groups, Korematsu-style deference is now officially out the window. Viewed through the Roman Catholic Diocese lens, Sunstein argues, Korematsu would have won. That is why he calls the new case the “anti-Korematsu” of our time.

The comparison is an interesting one, and even Sunstein admitted that some might consider his analogy “outrageous and even odious” given that many people who repudiate Korematsu also disagree with the holding of Roman Catholic Diocese. He predicted and addressed that criticism as follows:

This objection puts a bright spotlight on the limitations of analogical reasoning. Roman Catholic Diocese and Korematsu are alike in many ways, and different in many ways as well. The claim here is that insofar as the Roman Catholic Diocese Court was willing to vindicate antidiscrimination principles under exceedingly unusual circumstances posing severe risks, and to do so with genuinely strict scrutiny, it reflected an approach that is directly antithetical to that in Korematsu.

The government’s WWII-era incarceration of Japanese Americans has been previously used to draw analogies to government’s COVID-19 restrictions. In April 2020, churchgoers said in court papers that Kentucky Gov. Andy Beshear (D)’s COVID-19 restrictions were similar to those in Korematsu. (Beshear did not order people into alleged “concentration camps,” however.) Conservative Wisconsin Supreme Court Justice Rebecca Bradley also drew an analogy during oral arguments in May 2020 between COVID-19 restrictions by Gov. Tony Evers (D) and the actions in Korematsu. (Evers also did not order people into camps; still, Bradley called the Governor’s orders “tyranny.”)

Sunstein’s comparison is less blunt, as it examines the rationale for the court’s holdings and not the underlying government action. But it sums up as follows:

It reflects intense concern about discrimination, even in extraordinary circumstances, in which human lives are on the line. In the face of a plausible claim of discrimination, it reflects a willingness to second-guess official judgments, even though those judgments were not self- evidently mistaken. It is our anti-Korematsu.

Sunstein went on to compare Roman Catholic Diocese with another U.S. Supreme Court case, Railway Express Agency, Inc. v. New York, which upheld an ordinance that banned the sale of advertising on delivery trucks. The core issue of generality—whether a government action is generally applicable to all—is another interesting facet of the case.

[Photo by Jeenah Moon/Getty Images]