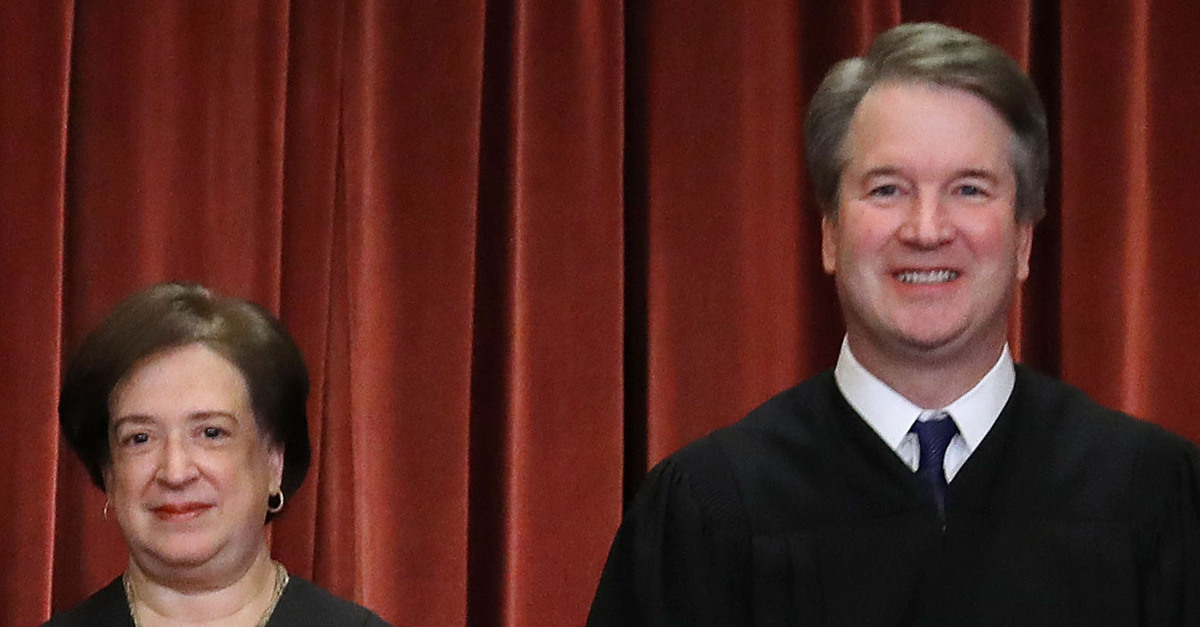

Justices Kagan and Kavanaugh

After a three-judge district court found that congressional district maps were designed to dilute Black voting strength in Alabama, the Supreme Court on Monday allowed the maps to be used during the 2022 midterm elections—over the fierce and furious objections of a dissent that called attention to the conservative majority’s frequent use of the so-called “shadow docket.”

Stylized as Merrill v. Milligan, the case turns on a group of voters, civil rights groups and faith organization who filed a lawsuit alleging that Alabama’s newly drawn congressional districts impermissibly “packed” one-third of the state’s Black voters into a single congressional district while “cracking” the remaining Black voters across three congressional districts in violation of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA).

On Jan. 24, 2022, a three-judge panel sitting on a federal district court in Alabama agreed with the plaintiffs, citing the state’s “well-documented, pervasive, and sordid history of racial discrimination in the context of voting and political participation.” The GOP’s maps were blocked, and the state was ordered to draw at least two majority Black congressional districts in line with the VRA.

On Monday night, five members of the U.S. Supreme Court stayed that preliminary injunction. The result is that Alabama’s 2022 congressional elections will be held in line with the map found to have been created to maximize GOP gains at the expense of the state’s Black voters, who have substantially increased in population since the last census.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh wrote a separate concurrence to explain his vote and to respond directly to claims made by Justice Elena Kagan’s stinging and lengthy dissent. In concurrence, Kavanaugh was joined by Justice Samuel Alito. In dissent, Kagan was joined by Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Stephen Breyer. Chief Justice John Roberts, one of the principal architects of the VRA’s reduced standing in U.S. law, joined the liberals in voting against the stay authorized by his fellow conservatives—but did not endorse Kagan’s reasoning.

“Accepting Alabama’s contentions would rewrite decades of this Court’s precedent about Section 2 of the VRA,” the principal dissent argues. “For that reason, this Court goes badly wrong in granting a stay. There may—or may not— be a basis for revising our VRA precedent in light of the modern districting technology that Alabama’s application highlights. But such a change can properly happen only after full briefing and argument—not based on the scanty review this Court gives matters on its shadow docket.”

Kagan’s conclusion reiterates her opposition to the “shadow docket”–a phrase that has come to describe many uses of the court’s emergency docket but here refers to stays and injunctions to render real-world changes, while technically not ruling on the merits of any given legal issue:

Today’s decision is one more in a disconcertingly long line of cases in which this Court uses its shadow docket to signal or make changes in the law, without anything approaching full briefing and argument. Here, the District Court applied established legal principles to an extensive evidentiary record. Its reasoning was careful—indeed, exhaustive—and justified in every respect. To reverse that decision requires upsetting the way Section 2 plaintiffs have for decades—and in line with our caselaw—proved vote-dilution claims. That is a serious matter, which cannot properly occur without thorough consideration. Yet today the Court skips that step, staying the District Court’s order based on the untested and unexplained view that the law needs to change. That decision does a disservice to our own appellate processes, which serve both to constrain and to legitimate the Court’s authority. It does a disservice to the District Court, which meticulously applied this Court’s longstanding voting-rights precedent. And most of all, it does a disservice to Black Alabamians who under that precedent have had their electoral power diminished—in violation of a law this Court once knew to buttress all of American democracy.

Coined by University of Chicago law professor William Baude in 2015, the “shadow docket” refers to rulings decided outside the court’s regular docket without oral argument. The phrase, further popularized by legal journalist Adam Serwer and University of Texas Law Professor Steve Vladeck, has been criticized by conservatives as a new, pejorative way some academics describe a routine manner the Supreme Court has long issued rulings.

Kavanaugh echoed that criticism [emphasis in original]:

To begin with, the principal dissent is wrong to claim that the Court’s stay order makes any new law regarding the Voting Rights Act. The stay order does not make or signal any change to voting rights law. The stay order is not a ruling on the merits, but instead simply stays the District Court’s injunction pending a ruling on the merits.

“The principal dissent’s catchy but worn-out rhetoric about the ‘shadow docket’ is similarly off target,” Kavanaugh continues. “The stay will allow this Court to decide the merits in an orderly fashion—after full briefing, oral argument, and our usual extensive internal deliberations—and ensure that we do not have to decide the merits on the emergency docket. To reiterate: The Court’s stay order is not a decision on the merits.”

In explaining his reasoning, Kavanaugh cites the Purcell principle, an inconsistently applied admonition from the nation’s high court that says, in the concurrence’s words, “federal district courts ordinarily should not enjoin state election laws in the period close to an election.”

“When an election is close at hand, the rules of the road must be clear and settled,” Kavanaugh elaborates. “Late judicial tinkering with election laws can lead to disruption and to unanticipated and unfair consequences for candidates, political parties, and voters, among others. It is one thing for a State on its own to toy with its election laws close to a State’s elections. But it is quite another thing for a federal court to swoop in and re-do a State’s election laws in the period close to an election.”

Kagan, for her part, rejects the applicability of the principle because the change demanded by the district court was made several months before any ballots will be cast in any step of the multi-step process.

Again, the dissent at length:

Alabama cannot here invoke the so-called Purcell principle, which disfavors changing election rules at the eleventh hour. Alabama contends that the District Court’s order comes too late because changing the map now may confuse voters who are moved to new precincts, and may hurt “non-major-party candidates” who “have to scramble to obtain” new signatures. But the District Court was right to say that “this case is not like Purcell because we are not ‘just weeks before an election.’” The general election is around nine months away; the primary date is in late May, about four months from now. Even the first day of absentee primary voting (which Alabama has leeway to modify) is March 30, more than two months after the court issued its order.

The dueling legal analyses from Kavavaugh’s concurrence and Kagan’s dissent also cite other timelines in shoring up their arguments.

“The District Court ordered that Alabama’s congressional districts be completely redrawn within a few short weeks,” Kavanaugh notes–complaining that legislators simply will not have enough time to comply with the district court’s injunction which he calls “a prescription for chaos for candidates, campaign organizations, independent groups, political parties, and voters.”

Not much moved by this, Kagan drily notes that Alabama’s GOP-dominated state “legislature enacted its current plan in less than a week.”

[image via Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images]