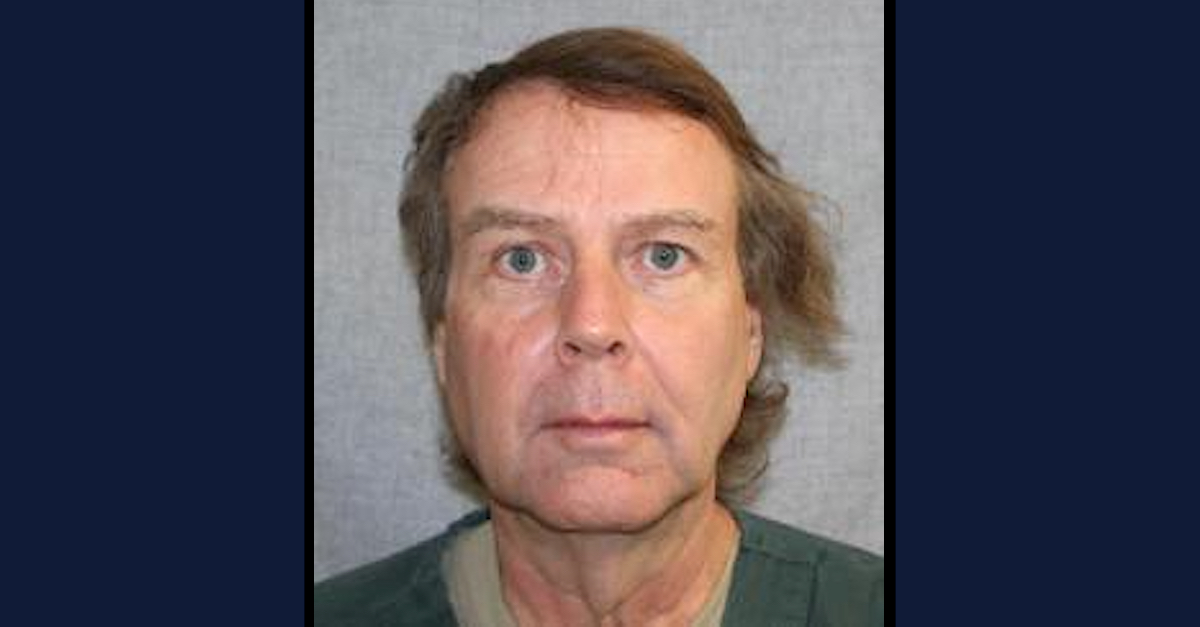

Douglas K. Uhde appears in a Wisconsin Department of Corrections booking photo dated March 17, 2020. The 6’4″ Uhde was listed in DOC records as having “absconded” from active community supervision.

A Wisconsin man who killed a judge and then wounded himself Friday morning had been previously sentenced to serve six years in prison by the same judge he attacked. That’s according to statements by the Wisconsin Department of Justice and state court records.

The case that connected alleged triggerman Douglas K. Uhde and Judge John Roemer was a burglary and weapons case which resulted in a legally awkward appeal, but Uhde’s criminal history is much more complicated.

AG Says Judge Shot, Killed in “Targeted Attack”

The Wisconsin DOJ alleged late Saturday afternoon that Uhde, now 56, shot and killed Roemer, 68, in the retired judge’s Town of New Lisbon home. New Lisbon is in Juneau County about an hour and twenty minutes northwest of Madison.

The DOJ said someone else was also in the home when the attack started around 6:30 a.m. That someone, whose identity is not clear, managed to escape to a neighbor’s house to call for help. Law enforcement responded, and a standoff ensued. Attempts at a negotiation failed, according to the DOJ.

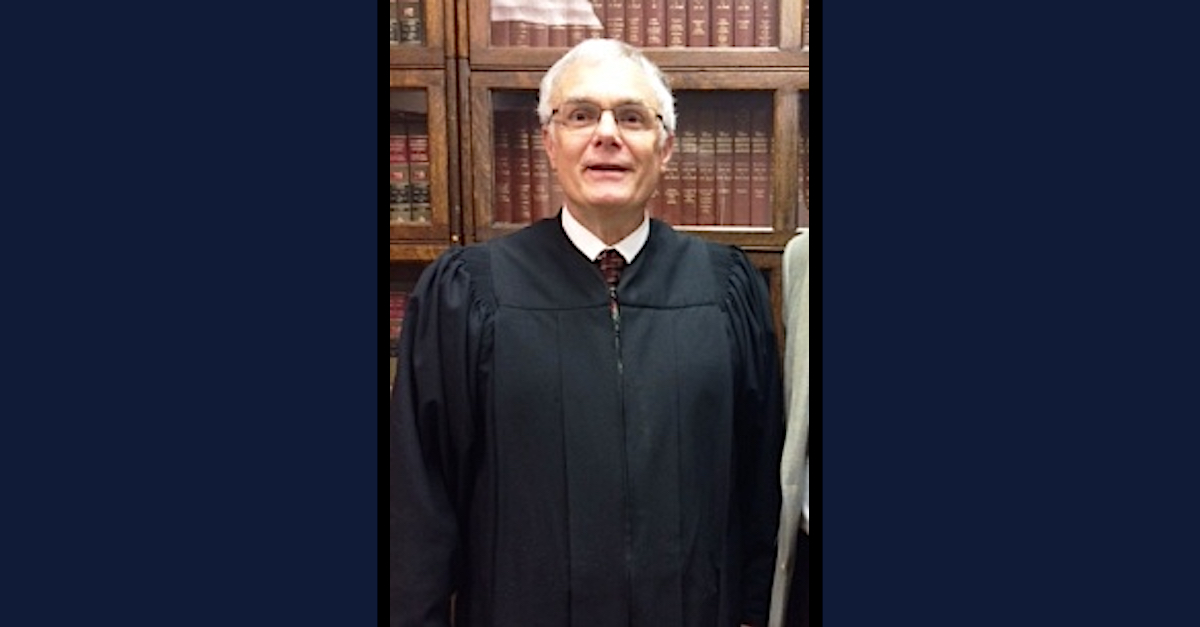

Wisconsin Circuit Court Judge John P. Roemer appears in a photo taken from a 2009 judicial branch newsletter. The same photo appeared in a 2004 newsletter.

A tactical team moved in around 10:17 a.m., the DOJ said. Officers found the judge dead in his own home and Uhde in the basement suffering from an apparent self-inflicted gunshot wound.

The officers began lifesaving measures and took Uhde to a hospital; he remains in critical condition as of Saturday, the DOJ indicated.

Milwaukee ABC affiliate WISN said Roemer had been “zip-tied to a chair in his home” and “shot dead.”

The DOJ said law enforcement officers recovered a firearm from the scene but did not say who owned it or what type of gun was used.

On Friday, Wisconsin Attorney General Josh Kaul said the incident appeared to have been a “targeted act . . . related to the judicial system.”

Kaul also suggested that the shooter — since identified as Uhde — apparently wished to target other victims.

Citing unnamed law enforcement sources, the Milwaukee Journal-Sentinel on Friday evening said Gov. Tony Evers (D) was one of the targets; radio news host John Mercure at WTMJ-Am in Milwaukee said the shooter was a member of a militia who had a “hit list.”

Sources tell me that a former judge has been shot and killed in Mauston by a militia member with a hit list. Newser planned for 4:30p.

— John Mercure (@JohnMercure) June 3, 2022

ABC News, NBC News, the New York Post, Reuters, the Daily Beast, and Madison, Wisconsin CBS affiliate WISC all reported that Uhde may have also desired to target Gov. Gretchen Whitmer (D-Mich.) and U.S. Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.). The information was sourced from unnamed law enforcement officials.

When asked by the Journal-Sentinel about whether Evers was a possible target, the Wisconsin governor’s office said it had a policy of not discussing security matters. Reuters said Whitmer’s office acknowledged that the governor of Michigan’s name “appeared on the Wisconsin gunman’s list” but would not comment further.

Kaul refused on Friday to directly state whether an actual list of targets had been collected as evidence but confirmed the shooter may have desired to harm other targets.

The DOJ reiterated on Saturday that the “incident appears to be a targeted act” but noted that there was “no immediate danger to the public.” It did not confirm or deny the reports that the shooter may have had militia connections.

Judge John Roemer was photographed during a meet-and-greet. (Image via the Wisconsin legislature.)

Uhde’s Criminal History

According to Wisconsin court records, Judge Roemer sentenced Uhde as part of a four-count case that commenced in August 2001 in Adams County.

Uhde was charged in that matter with (1) burglary while armed with a dangerous weapon (a felony), (2) carrying a concealed weapon (a misdemeanor), (3) possessing a short-barreled shotgun or rifle (another felony), and (4) possessing a weapon as a previous felon (yet another felony).

Roemer sentenced Uhde on Nov. 10, 2005. On the top count — burglary — Roemer issued a six-year prison sentence and a nine-year period of extended supervision, the court records indicate. The other counts resulted in sentences of nine months, one year, and one year, respectively. All of the sentences ran concurrently (at the same time).

The four-year-long case had a slightly bizarre procedural posture. First, however, a walk through Uhde’s additional criminal history is necessary.

Uhde previously faced some sort of an extradition proceeding in Adams County, Wisconsin, in 1999. The circumstances of that case are unclear from the available online court records. Wisconsin jail records say Uhde had at least one out-of-state conviction; however, no information as to where or when is included in the data.

He later faced a felony escape from arrest charge in 2006. He pleaded no contest to that charge in early 2007 and was sentenced to serve nine months — but the punishment was ordered to run consecutive to the 2001 Adams County burglary and weapons case.

In 2007, he was charged with three additional crimes: (1) fleeing or eluding an officer as a vehicle operator (a felony), (2) driving or operating a vehicle without consent (another felony), and (3) obstructing an officer (a misdemeanor). Court records say he was found guilty after jury trial in this matter. That case resulted in a 2008 sentencing hearing.

Only the 2001 case involved Judge Roemer — at least in part.

The original court docket says a different judge, James Miller, sentenced Uhde on April 2, 2002. That’s well before Judge Roemer’s sentence.

The case actually went all the way up and down the legal chain in Wisconsin before Judge Roemer was called to handle it. First, the case went to the Wisconsin Court of Appeals, the state’s intermedia appellate bench.

A Twisted Appeal

According to a Wisconsin Court of Appeals opinion and other appellate court records, Uhde pleaded no contest in the burglary and weapons case but tried to walk back his plea. The Court of Appeals took the case on Jan. 6, 2003, issued an opinion on Jan. 29, 2004, and was asked to reconsider that opinion on Feb. 18, 2004. Surprisingly, the court agreed to do so. Just five days later, and in a legally rare move for an appellate court, the Court of Appeals withdrew its Jan. 29 opinion on Feb. 23, 2004.

After more litigation, the appellate court sought advice from the state’s highest court, the Wisconsin Supreme Court, via a mechanism known as a certified question of law. The Supreme Court took the case on April 20, 2004, and pushed it back down to the Court of Appeals on Sept. 16, 2004, after a concession by the state that Uhde should be allowed to withdraw his no contest plea to Judge Miller.

On October 28, 2004, the Wisconsin Court of Appeals issued an opinion which explained the mess. According to that document, Uhde argued that Judge Miller made a mistake when he explained the sentence and made another mistake when he took the plea. Specifically, Uhde said Judge Miller failed to tell him that truth-in-sentencing laws required him “to serve the entire period of initial confinement without opportunity for good time or parole.” Uhde also argued that the trial judge “misstated the elements of the burglary charge” during a plea colloquy — that’s when the court accepted the plea itself.

“The State concedes error on the latter issue,” the appellate court said. “We therefore reverse and remand with directions to grant Uhde’s plea withdrawal motion.”

The opinion continued by recapping the state’s sudden about-face as to Uhde’s ability to withdraw his plea and the court’s about-face as to its first opinion on the case:

When we first considered Uhde’s appeal, the State disputed both of Uhde’s plea withdrawal arguments. We issued a decision reversing and remanding for a rehearing on Uhde’s plea withdrawal motion. After further consideration, we withdrew our opinion and certified the appeal to the supreme court on the question whether a circuit court must inform a defendant, during the plea colloquy, that initial confinement under truth-in-sentencing will not be reduced by good time or parole. The supreme court granted certification. After the supreme court accepted the case, the State submitted a brief reversing its position on Uhde’s burglary misstatement claim. The State conceded before the supreme court that Uhde is entitled to plea withdrawal based on the trial court’s misstatement of the elements of burglary. Uhde then asked the supreme court to summarily dispose of the appeal or vacate the certification. On September 16, 2004, the supreme court granted Uhde’s motion for summary disposition and remanded the case to this court for further proceedings “in light of the State’s concession in its brief . . . that defendant-appellant is entitled to plea withdrawal.” Although our review of the State’s supreme court brief does not, in our view, reveal a clear explanation as to why the State is now confessing error, we conclude that the supreme court must have deemed the concession appropriate or that court would not have vacated the certification.

The Court of Appeals sent the case back to the circuit court with instructions to grant Uhde’s request to withdraw his plea and to concomitantly vacate Uhde’s convictions. The appeals court did not consider Uhde’s additional truth-in-sentencing claims because the no contest pleas were no more and, therefore, neither were the sentences.

The case then went back down the judicial hierarchy to the circuit court and landed in Judge Roemer’s lap. Roemer was assigned to hear the case on Feb. 7, 2005, according to court records. Uhde wound up pleading guilty or no contest — again — and receiving the aforementioned six-year sentence.

More Appeals in Vehicle Theft Case

At least one of Uhde’s other cases also ended up before the appeals courts. He complained of ineffective assistance of counsel and prosecutorial misconduct (among other things) after his 2008 conviction for fleeing in a vehicle and eluding an officer. According to an appellate brief, he claimed that a “prosecutor planted evidence and encouraged false testimony.”

This appeal was also complex, but not to the extent of the previous case.

The trial court judge seemed inclined to believe that Uhde’s defense attorney was at least somewhat ineffective, according to a state appellate brief. The state said it would not “second-guess that determination.” Part of the issue was that Uhde’s counsel allegedly failed to give case documents to the defendant himself and then didn’t show up to an evidentiary hearing to answer questions about the apparent lapse. Despite the aforementioned air of acquiescence, the trial judge still jettisoned Uhde’s overall complaints. That’s because Uhde failed to draw up subpoenas on his own volition to force his defense attorney to show up to the hearing.

That’s something even the state conceded was unreasonable.

“Whether or not Uhde had a technical responsibility to issue the subpoena to ensure his trial counsel’s appearance, the State believes that fairness requires Uhde be given another opportunity,” the state wrote.

The state therefore asked the appellate court to allow Uhde the chance to have a hearing on that matter but to otherwise toss his other complaints. The Court of Appeals agreed to grant that narrow window of relief.

Among Uhde’s other complaints, per the state, were things like this (legal citations omitted):

Uhde alleges that law enforcement planted a “phantom vehicle” on an “unidentified parcel of land” and depicted it in exhibits in order to incriminate Uhde. Uhde offers no support for these claims — as to whom, when, and where this was allegedly accomplished. His challenges to photographic exhibits, which he argues have some discrepancies with testimony elicited at trial, were issues for cross-examination at trial.

In other words, if Uhde’s allegations were true, then those claims should have been lodged in front of the jury, not in front of the appellate court.

The case went back down to the circuit court for the necessary hearing. Then, when that was done, it went back up to the appellate court. The circuit court found that Uhde suffered no prejudice because of his attorney’s alleged misgivings because the evidence against him was “very, very strong.”

Uhde appealed again. Prosecutors said this time that Uhde was, in essence, making things up at this point:

Uhde’s Background Facts section of his brief is full of claims not supported by the record. It does not contain citations to the record. Much of the information presented as fact is purely argument of what Uhde believes happened. The state disputes many of the allegations in this section of Uhde’s brief.

The state then recounted blow-by-blow the case that resulted in the vehicle theft conviction. The basic facts as laid out in the appellate brief were that Uhde stole a truck from an Easter Seals property in Wisconsin Dells, ditched some of the equipment attached to the truck, stole a license plate from another truck, and started contacting a former girlfriend. The authorities caught Uhde leaving a hospital parking lot — a hospital from which he apparently dialed his ex — and then checking out the ex’s residence; he was driving the stolen truck donned with the stolen plate.

“A high speed chase ensued with speeds around 90 or 95 miles per hour,” the appellate brief said. “Uhde drove the car into a ditch and into a field. Officers set up a perimeter to contain the truck and driver.”

That effort was at first unsuccessful: the truck “careened off a tree,” and a “puff of smoke from the engine” apparently “started a grass fire.” That fire eventually “destroyed the truck.”

Search dogs tracked the defendant to where offices found him “lying flat on the ground near a log.” He admitted approaching his ex-girlfriend’s house and calling her from the hospital.

The Court of Appeals denied Uhde’s request for postconviction relief in this vehicle theft case when all was said and done.

Even More Appeals

Uhde also tried to appeal his conviction for escape. The Court of Appeals rejected that habeas corpus proceeding. According to its terse two-page opinion:

Uhde was an inmate at Fox Lake Correctional Institution and walked away from a job site in Baraboo. Uhde pled no contest to the charge. Uhde now argues that venue in Dodge County was improper because he committed the crime in Sauk County, where he walked away from the job site. We reject the argument.

The reason, the Court of Appeals said, was because the prison where Uhde was incarcerated was in Dodge County — thus making that venue proper. The job site in the other county, the court rationed, was not relevant to the calculus.

It’s unclear what Uhde’s legal future may hold from here given his reported medical condition from the apparent self-inflicted gunshot wound.

The Wisconsin Department of Justice has asked anyone with information about Uhde to call (608) 266-1221.

The DOJ said it would turn the case over to the Juneau County District Attorney when the factual investigation into the judge’s death concludes.

The DOJ’s most recent press release, Uhde’s prison history, and some of his appellate records are here:

[Mugshots via the Wisconsin Department of Corrections.]