Hadley Palmer. (Left mugshot from the Greenwich Police Dept. and right mugshot from the Connecticut Dept. of Corrections.)

A Connecticut heiress who confessed in court to filming secret videos of children without their knowledge could serve as little as 90 days behind bars while also keeping the details of her offenses shielded from the public, according to court documents signed by a judge on Feb. 9.

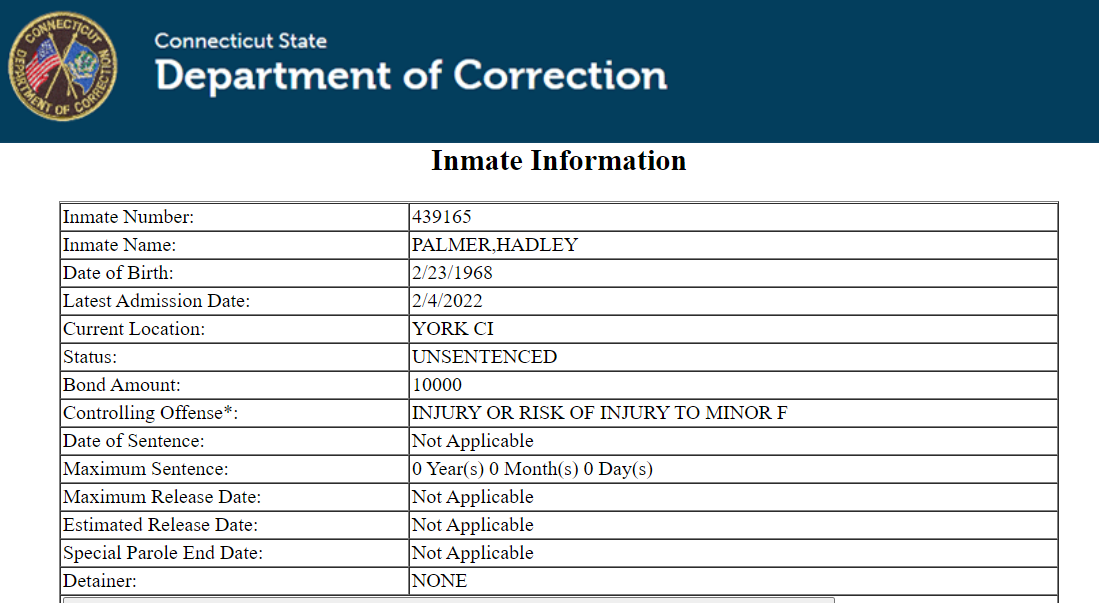

Hadley Palmer, 53, turned herself in at the Greenwich Police Department last October after a judge signed out a warrant for her arrest. The charges against Palmer all stemmed from incidents in 2017 and 2018 when she allegedly “photographed, filmed and recorded specific individuals without their knowledge or consent, and under circumstances where those individuals were not in plain view and had a reasonable expectation of privacy, and at least one photograph taken by the defendant depicted a person who was a minor,” according to court papers.

Palmer made her first court appearance just a few days after her arrest, the court records indicate. She informed Judge John F. Blawie that she hoped to enroll in an accelerated rehabilitation program offered by the state during that initial meeting.

Upon hearing that Palmer planned to explore the program, which allows low-level offenders to avoid jail following their first offense, most of the record in the case became sealed. Judge Blawie stated in a court filing that the initial sealing of the file was not necessarily his decision; rather, Palmer’s decision to enter the pretrial accelerated rehabilitation program “resulted in the temporary sealing of the file pursuant to statute.” In other words, it was the statute, not the court per se, that both triggered and forced the initial seal.

In the end, Palmer did not pursue the accelerated rehab program. Instead, she chose to focus on working out a deal with prosecutors. According to a plea agreement, Palmer admitted to three counts of voyeurism and one count of causing a risk of injury to a child.

On Jan. 14, Palmer filed a broader request to seal the contents of her court file, and a few days later, she signed a plea agreement by which prosecutors would recommend no less than 90 days but no more than 60 months behind bars. That period of incarceration would also be followed by 30 years of probation, and Palmer would have to register as a sex offender, according to the plea deal paperwork. A 30-year protective order is contemplated involving what appear to be the victim or victims — though their names are blacked out of the record. The order bans contact or physical presence within 100 yards of the individuals named.

Prosecutors wrote in the plea deal that Palmer could not own a camera phone, camera, or video recorder upon her release from prison unless she obtains special permission; the defendant is also not allowed to have any “unsupervised or overnight contact or communication with minors, including contact or communication with minors using the internet or any other digital or written communication medium.”

Palmer reported to a correctional facility in early February (inmate record above from Connecticut Dept. of Correction) but will not be sentenced until August.

In exchange for the admission of guilt, prosecutors dropped the more severe felony charges of employing a minor in an obscene performance, conspiracy to employ a minor in an obscene performance, and second-degree child pornography. Prosecutors also agreed to file no additional charges against Palmer and to drop all charges related to an alleged violation of the conditions of her pretrial release. That alleged incident happened just days after her arrest. According to online court records, the pretrial release matter was proceeding as a separate case.

On Tuesday, the Greenwich Police Department told Law&Crime that they were not at liberty to share any details of the case but did reveal that the three victims were all minors.

The details and timeline of Palmer’s admitted offenses, the terms of her pretrial release, and how she allegedly violated those terms are all a mystery, however, because last week Judge Blawie opted to support Palmer’s request to keep the court file sealed. Blawie cited the benefits the sealing of the file would have for the victims in an aptly titled Motion to Seal:

In her motion, the defendant argues that the court should order the entirety of the court file sealed, as such an order is the only practical means to preserve the privacy interests of the victims. Specifically, she argues that the details of the charges involve confidential identifying information about the victims and that those privacy interests outweigh the public’s interest in viewing the court file. The defendant contends that dissemination of the contents of the court file would reveal the victims’ identities within the communities where they reside and that no reasonable alternatives exist other than granting the defendant’s request. The state concurs, and while this is not a situation where a stipulation of the parties alone is ever sufficient to order sealing, in this instance, the court agrees.

Blawie then cited P.B. Sec. 42-49A as his rationale to lock the public out of the material. That citation references the Connecticut Practice Book, a lengthy document that governs legal proceedings in the Nutmeg State. The broader language of that provision generally indicates that records are open to the public:

Except as otherwise provided by law, there shall be a presumption that documents filed with the court shall be available to the public.

[ . . . ]

Upon written motion of the prosecuting authority or of the defendant, or upon its own motion, the judicial authority may order that files, affidavits, documents, or other materials on file or lodged with the court or in connection with a court proceeding be sealed or their disclosure limited only if the judicial authority concludes that such order is necessary to preserve an interest which is determined to override the public’s interest in viewing such materials. The judicial authority shall first consider reasonable alternatives to any such order and any such order shall be no broader than necessary to protect such overriding interest. An agreement of the parties to seal or limit the disclosure of documents on file with the court or filed in connection with a court proceeding shall not constitute a sufficient basis for the issuance of such an order.

The section implies that most records can be redacted — assuming the redaction would accomplish the contemplated privacy goals. Here, the parties and the judge agreed it would not. In sealing the written court filings, the judge explicitly referenced subsection (f)(1) of the aforementioned Practice Book section. That subsection governs “[a] motion to seal the contents of an entire court file” (emphasis added). A separate but almost entirely analogous section of the Practice Book, section 42-49, deals with court proceedings, not court documents.

The New York Times reported that Palmer reported to the York Correctional Institution, a women’s prison, on Feb. 4 even though her sentencing is not until August.

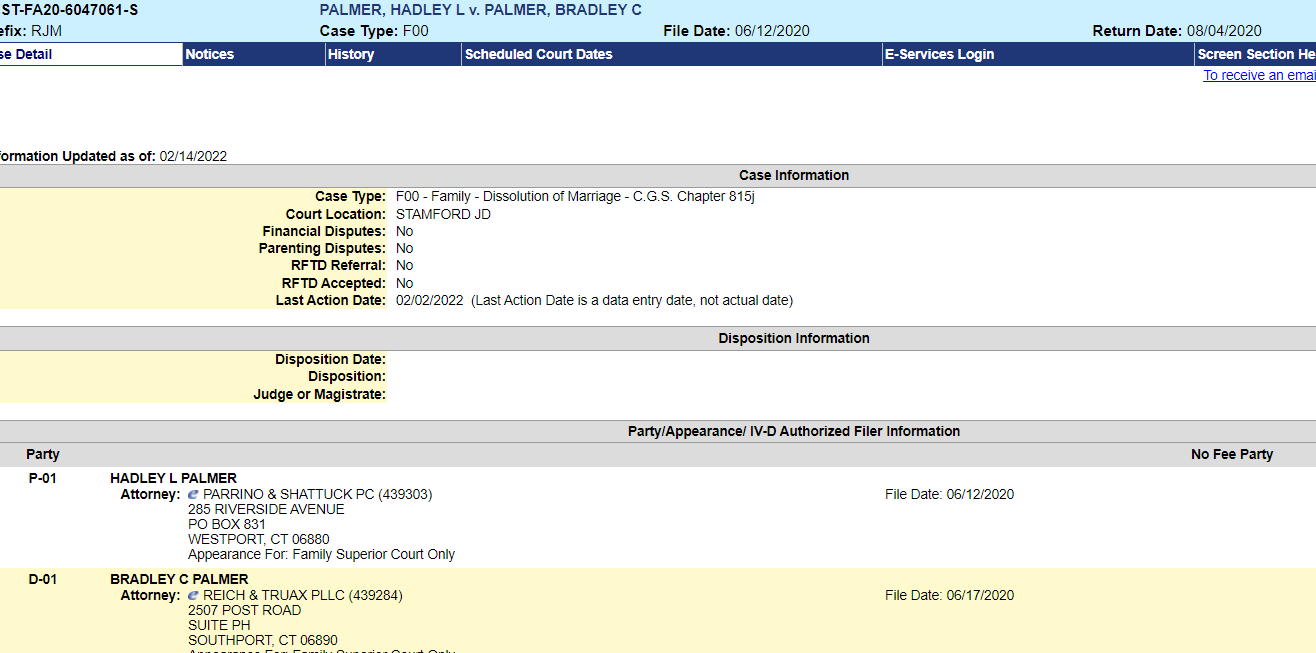

Palmer filed for divorce from her husband in 2020 (Connecticut Family Court docket).

Under Connecticut state law, two of the charges to which the defendant pleaded guilty carry a maximum five-year prison term; the other two carry a maximum ten-year term.

Prosecutors, however, are seeking a complicated sentence.

According to the plea forms, the state desires count one (voyeurism) and count four (risk of injury to a child) to result in a nominal sentence of ten years — but that’s all in theory. Most of that contemplated time behind bars would result in a “suspended” sentence — one that’s judicially brushed away — after the defendant serves somewhere between 90 days in jail or 60 months (five years) in prison followed by 20 years of probation.

Counts two and three (both voyeurism) would result in a nominal sentence of five years, but here prosecutors are comfortable with the entire sentence being suspended. Twenty years of probation are also contemplated.

Technically speaking, counts one and four would be served concurrent to one another but consecutive to counts two and three — not that it likely will matter much given the suspended nature of the sentences on counts two and three.

Prosecutors wrapped it all up as follows:

The intent of this recommendation is to achieve a total effective sentence of a term of imprisonment of 15 years, execution suspended after Palmer serves not less than 90 days and not more than 60 months, and 20 years of probation . . . Palmer agrees that she will not oppose this total effective sentence recommendation.

The charge of injury to a child — to which Palmer did enter a guilty plea — means that at least one victim was under the age of 16 but appears to have been over the age of 13. (If the victim was under 13, Connecticut law states that a defendant “shall be sentenced to a term of imprisonment of which five years of the sentence imposed may not be suspended or reduced by the court” — and, here the court did indeed suspend the sentence.)

Palmer and her husband, Brad Palmer, have been locked in divorce proceedings for almost two years, and the court docket portends at least another two years of litigation before they might be able to resolve the details of their split. The defendant Palmer filed for divorce from her husband back in June 2020. Brad Palmer is also battling two lawsuits related to his hedge fund in the state of Connecticut, according to the court docket.