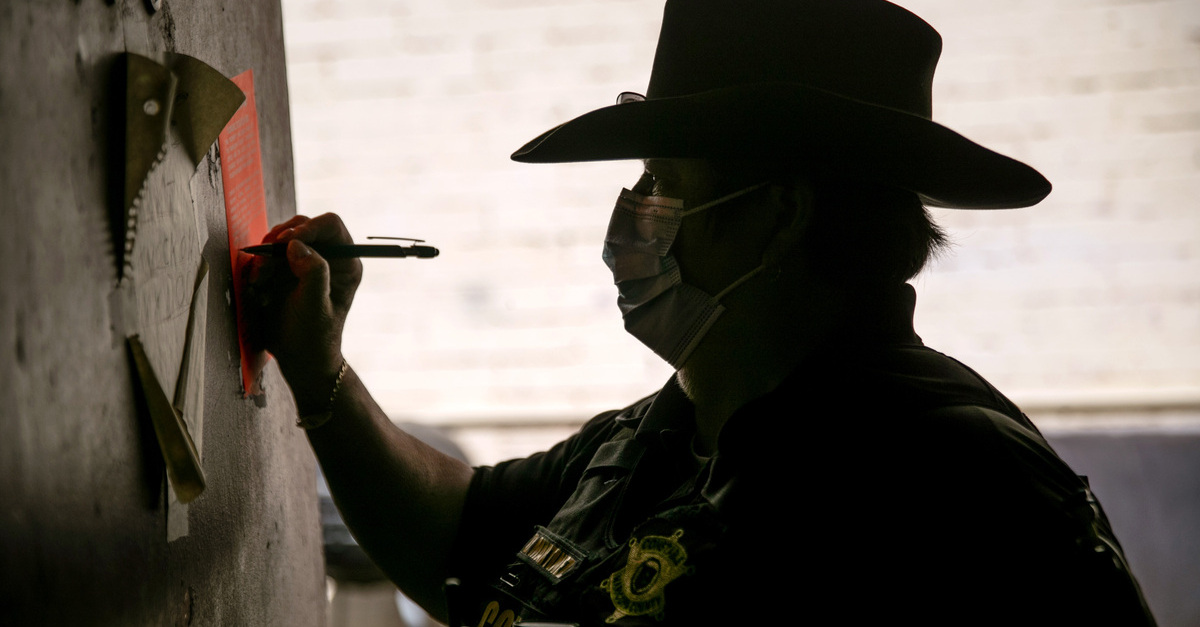

Maricopa County constable Darlene Martinez signs an eviction order on October 7, 2020 in Phoenix, Arizona. Thousands of court-ordered evictions continue nationwide despite a Centers for Disease Control (CDC) moratorium for renters impacted by the coronavirus pandemic. Although state and county officials say they have tried to educate the public on the protections, many renters remain unaware and fail to complete the necessary forms to remain in their homes. In many cases landlords have worked out more flexible payment plans with vulnerable tenants, although these temporary solutions have become fraught as the pandemic drags on.

A federal judge on Wednesday tossed a nationwide eviction moratorium originally promulgated by the Donald Trump era U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as a response to the ongoing coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic.

The order, which has only been enforced piecemeal across the country as many landlords have ignored it and courts have been loath to enforce it, has staved off eviction and homelessness for thousands upon thousands of Americans. Those families now face an increasingly uncertain future.

In a 20-page memorandum opinion, Trump-appointed U.S. District Judge Dabney Friedrich found that CDC Director Dr. Rochelle Walensky exceeded her authority when she issued the “Temporary Halt in Residential Evictions To Prevent the Further Spread of COVID-19” order in early September 2020 at the behest of the 45th president.

The order was subsequently extended and later endorsed by both the U.S. Congress and current President Joe Biden.

“[T]he CDC order must be set aside,” the court ruled — stressing that vacating the order nationally was in line with “settled precedent” and the relevant federal law governing administrative agencies.

The CDC missive, twice since renewed, declared that “a landlord, owner of a residential property, or other person with a legal right to pursue eviction or possessory action shall not evict any covered person” and provided guidelines for tenants to claim housing safe harbors amidst the broad and deep economic turmoil caused by the pandemic.

Three real estate management companies sued because some of their tenants stopped paying rent, invoked the protections of the CDC’s eviction moratorium, and therefore could not be evicted.

The plaintiffs alleged various procedural complaints against the CDC, but the D.C. District Court began and ended its analysis by determining the agency had exceeded its authority with the order.

Judge Friedrich employed the administrative law framework from the landmark case of Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc., which is a multiple-step inquiry that determines whether or not an administrative agency is entitled to judicial deference over its own interpretation of a statute written by Congress.

The inquiry’s first step is to assess whether or not “Congress has directly spoken to the precise question at issue,” which is another way of asking if the statute is ambiguous or not. Only if the statute is found to be ambiguous by a court will the additional steps be considered. Here, the number of steps the court allows itself to take is often determinative in how a decision is reached.

The court’s answer to the first question is typically dispositive. And that’s what happened here.

“At Chevron’s first step, this Court must apply the ‘ordinary tools of the judicial craft,’ including canons of construction,” she wrote. “These canons confirm what the plain text reveals. The Secretary’s authority does not extend as far as the Department contends.”

Judge Friedrich said the statute at issue is clear — despite numerous attempts by the CDC to offer counter explanations for what certain terms in the Public Health Service Act mean.

“The Department’s interpretation goes too far.” the court said. “The first sentence of [the statute] is the starting point in assessing the scope of the Secretary’s delegated authority. But it is not the ending point. While it is true that Congress granted the Secretary broad authority to protect the public health, it also prescribed clear means by which the Secretary could achieve that purpose. And those means place concrete limits on the steps the Department can take to prevent the interstate and international spread of disease. To interpret the Act otherwise would ignore its text and structure.”

The court also offered another reason to revoke the moratorium:

[T]the canon of constitutional avoidance instructs that a court shall construe a statute to avoid serious constitutional problems unless such a construction is contrary to the clear intent of Congress. An overly expansive reading of the statute that extends a nearly unlimited grant of legislative power to the Secretary would raise serious constitutional concerns, as other courts have found. Congress did not express a clear intent to grant the Secretary such sweeping authority.

…

Accepting the Department’s expansive interpretation of the Act would mean that Congress delegated to the Secretary the authority to resolve not only this important question, but endless others that are also subject to “earnest and profound debate across the country.” Under its reading, so long as the Secretary can make a determination that a given measure is “necessary” to combat the interstate or international spread of disease, there is no limit to the reach of his authority.

“In sum, the Public Health Service Act authorizes the Department [of Health and Human Services] to combat the spread of disease through a range of measures, but these measures plainly do not encompass the nationwide eviction moratorium set forth in the CDC Order,” the opinion continued. “Thus, [HHS] has exceeded the authority provided in § 361 of the Public Health Service Act.”

Read the full order below:

[image via John Moore/Getty Images]