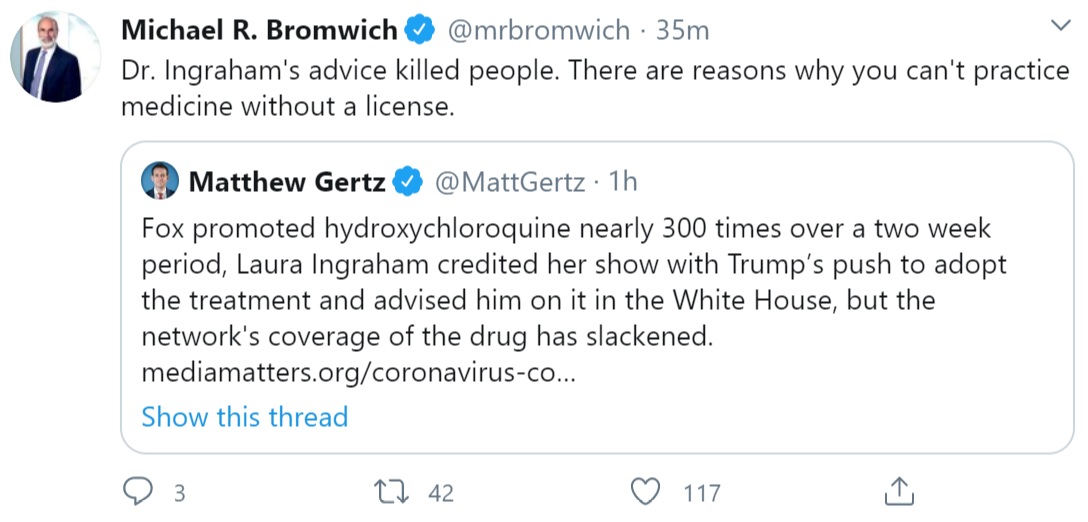

In a swiftly-deleted tweet that was online for perhaps half an hour Wednesday morning, attorney Michael R. Bromwich dragged Fox News Channel host Laura Ingraham for statements Ingraham made about the drug hydroxychloroquine.

“Dr. Ingraham’s advice killed people,” Bromwich said in the deleted tweet. “There are reasons why you can’t practice medicine without a license.” (Ingraham is a trained lawyer, not a doctor.)

Bromwich, who has represented former FBI Deputy Director Andrew McCabe and Christine Blasey Ford, made the comments in response to a tweet by Matthew Gertz of the progressive watchdog group Media Matters for America. Gertz was noting the degree to which Ingraham had “promoted” (to use Gertz’s words) the drug.

Bromwich’s recent criticism of Fox News Channel has also included this missive about a recent Sean Hannity controversy:

The family should sue Fox. https://t.co/BNSabyA4km

— Michael R. Bromwich (@mrbromwich) April 18, 2020

That said, Bromwich’s criticisms aren’t that far off from other, similar complaints:

Dr. Laura Ingraham doubles down on the #HydroxychloroquineHoax

Fox News has blood on their hands.

The lawsuits are lining up out the door, down the block and around the corner.@IngrahamAngle https://t.co/hppSZOnzaJ— Billy Baldwin (@BillyBaldwin) April 10, 2020

Hannity, for his part, has been clear to say he’s not the doctor in the room. Ingraham’s commentaries have largely looped in statements from Dr. Anthony Fauci, President Donald Trump, published studies, and government documents.

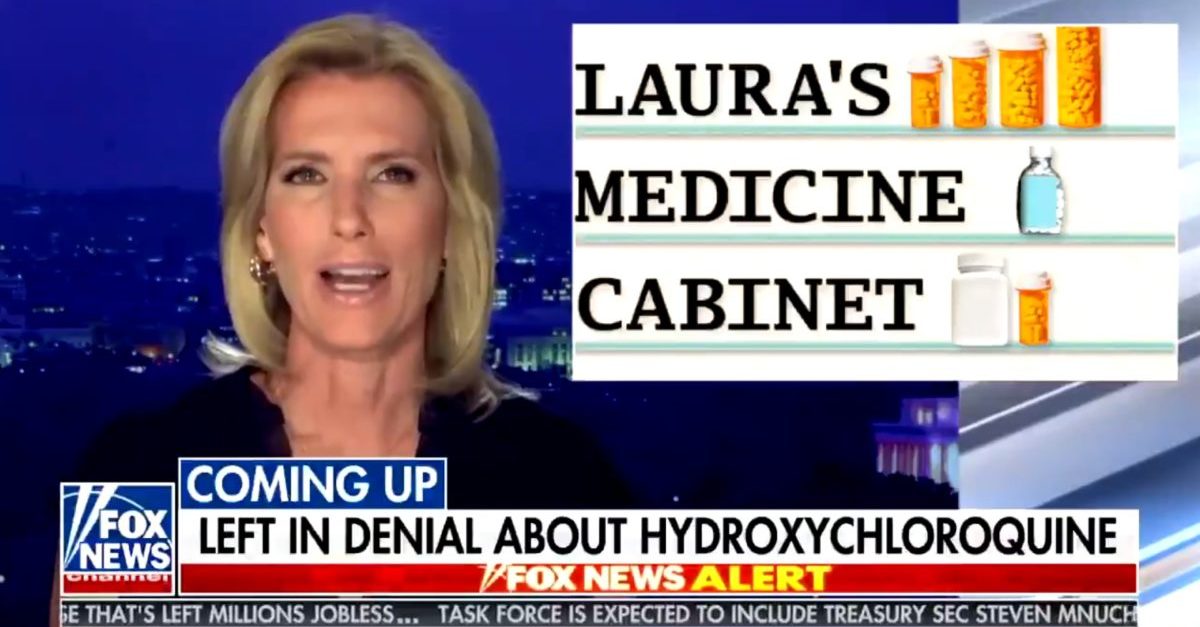

At one point, Ingraham talked about the drug with others in a segment called “Laura’s Medicine Cabinet,” which led to some other criticism:

Do not take pills from “Laura’s Medicine Cabinet.”

Talk to your doctor instead. https://t.co/7XN3hRYSRX

— Mike Hixenbaugh (@Mike_Hixenbaugh) April 10, 2020

Critics can complain all they want, but as a legal matter, journalists who talk about medical treatments on television are not practicing medicine without a license. Law&Crime has summarily addressed this issue, but it apparently needs to be repeated:

A state has the power to license professions in order to protect the public and to prevent unlicensed people from engaging in those professions. In New York, practicing medicine is defined as “diagnosing, treating, operating or prescribing for any human disease, pain, injury, deformity or physical condition.” Listening to a broadcast does not place a viewer into the type of personal contact predicated by licensing statutes.

Let’s walk through the analysis a little bit further this time around. It’s not up for debate that COVID-19 is a disease. Talking about hydroxychloroquine on television — even as a purported wonder drug — is certainly not an operation. Nor does a television segment diagnose someone. Diagnosis requires tests and observations, and television shows don’t test or observe audience members in a medical sense. Nor does a television host prescribe medicine. A journalist’s notebook or a commentator’s script are not the functional equivalents of a prescription pad. Television personalities cannot order drugs from a pharmacy for a viewer.

Finally, watching television is not a treatment. While the practice of medicine is broadly defined in New York and includes practicing medicine on the dead (through autopsies), it is a stretch to suggest that a news or opinion broadcast which discusses medical developments or setbacks amounts to treatment. Indeed, as another New York case which dealt primarily with statutes of limitations suggests, but does not directly hold, “treatment” is generally seen as something “provided . . . to the human body to address a physical condition or pain.” The key phrase there is “to the human body.” Television personalities speak; they do not do things to people’s bodies.

There is a dearth of case law on point, but suggesting that a television opinion host is practicing medicine is a far stretch. Even if a court were to agree that talking about promising therapies on television does constitute the practice of medicine, the New York statute itself provides an escape hatch of sorts. The licensed profession law states that it “shall not be construed to affect or prevent . . . the furnishing of medical assistance in an emergency.” While that language does not mention television, any host prosecuted by licensing authorities could argue affirmatively that the COVID-19 “emergency” allows her to “furnish” advice to viewers about the current race for a treatment or cure.

There are, obviously, First Amendment defenses at play as well. As one New York case which examined the unauthorized practice of medicine said, “While the State may constitutionally regulate certain activities, it may not do so in an unnecessarily broad manner thereby impinging upon fundamental personal liberties.” As a free speech matter, discussions about developmental medical treatments during a pandemic are of critical importance.

President Trump has touted the drug hydroxychloroquine time and time again. Some may even argue that some of his statements were influenced by Ingraham’s coverage. Either way, a much-debated recent study questioned the drug’s effectiveness as a treatment for COVID-19; another such study had to be aborted. Rational people around the world want to talk about the development of a cure. In America, the right to do so is in the Constitution.

[Image via screen capture from Fox News]