The California Supreme Court on Thursday ruled that keeping criminal defendants in jail before trial simply because they lack the ability to afford bail is unconstitutional.

“The common practice of conditioning freedom solely on whether an arrestee can afford bail is unconstitutional,” the tidy 29-page opinion reads. “What we hold is that where a financial condition is nonetheless necessary, the court must consider the arrestee’s ability to pay the stated amount of bail — and may not effectively detain the arrestee ‘solely because’ the arrestee ‘lacked the resources’ to post bail.”

Criminal justice reform advocates hailed the result.

“The California Supreme Court has just struck down the state’s money bail system as violating fundamental civil rights,” noted Alec Karakatsanis, the founder and executive director of Civil Rights Corps, via Twitter. “Our client Kenneth Humphrey has won his case, and hundreds of thousands of people will benefit.”

“This is a fantastic decision AND it relies on the California Constitution, so SCOTUS cannot reverse it,” Slate legal writer Mark Joseph Stern tweeted.

“[A]mazing victory!” Current Affairs Legal Editor Oren Nimni said via Twitter. “California Supreme Court finds that the cash bail system violates fundamental rights.”

“This is huge,” California Democratic Party Progressive Caucus Chair and civil rights attorney Amar Shergill tweeted. “Finally, California will stop jailing the poor because they are poor.”

The unanimous ruling by Associate Justice Mariano–Florentino Cuéllar is a thorough repudiation of the Golden State’s current bail system and all-but eliminates the ability of judges and prosecutors to hold defendants based on their ability to pay.

“Underlying [the current] arrangement is a major premise: that the state has a compelling interest in assuring the arrestee’s appearance at trial and protecting the safety of the victim as well as the public,” Cuéllar notes. “Yet those incarcerated pending trial — who have not yet been convicted of a charged crime — unquestionably suffer a ‘direct “grievous loss”‘ of freedom in addition to other potential injuries.”

“In principle, pretrial detention should be reserved for those who otherwise cannot be relied upon to make court appearances or who pose a risk to public or victim safety, but it’s a different story in practice,” the decision continues. “Whether an accused person is detained pending trial often does not depend on a careful, individualized determination of the need to protect public safety, but on the accused ability to post the sum provided.”

The court goes on to cite a working group report that found “some people currently in California jails who are safe to be released are held in custody solely because they lack the financial resources for a commercial bail bond, and other people who may pose a threat to public safety have been able to secure their release from jail simply because they could afford to post a commercial bond.”

And the impetus on public safety is equally paramount with the need for individual freedom, according to the court.

Defendants who pose “little or no risk of flight or harm to others,” are to be released with appropriate conditions. If a defendant does pose a flight or harm risk, however, a court still must undergo an exacting inquiry into “whether nonfinancial conditions of release may reasonably protect the public and the victim or reasonably assure the arrestee’s presence at trial.” But this is a high bar that includes several layers of analysis for courts.

The court explains at length:

If the court concludes that money bail is reasonably necessary, then the court must consider the individual arrestee’s ability to pay, along with the seriousness of the charged offense and the arrestee’s criminal record, and — unless there is a valid basis for detention — set bail at a level the arrestee can reasonably afford. And if a court concludes that public or victim safety, or the arrestee’s appearance in court, cannot be reasonably assured if the arrestee is released, it may detain the arrestee only if it first finds, by clear and convincing evidence, that no nonfinancial condition of release can reasonably protect those interests.

In lieu of cash bail, the court endorses various hallmarks of pre-trial release such as “as electronic monitoring, supervision by pretrial services, community housing or shelter, stay-away orders, and drug and alcohol testing and treatment.”

“No person should lose the right to liberty simply because that person can’t afford to post bail,” the decision reads. “[Humphrey’s] claim joins a ‘clear and growing movement’ that is reexamining the use of money bail as a means of pretrial detention.”

“It has been the honor of a lifetime to have represented Mr. Humphrey these last four years,” Karakatsanis added in a follow-up tweet. “The struggle very much continues to ensure that we don’t substitute one system of oppression for another.”

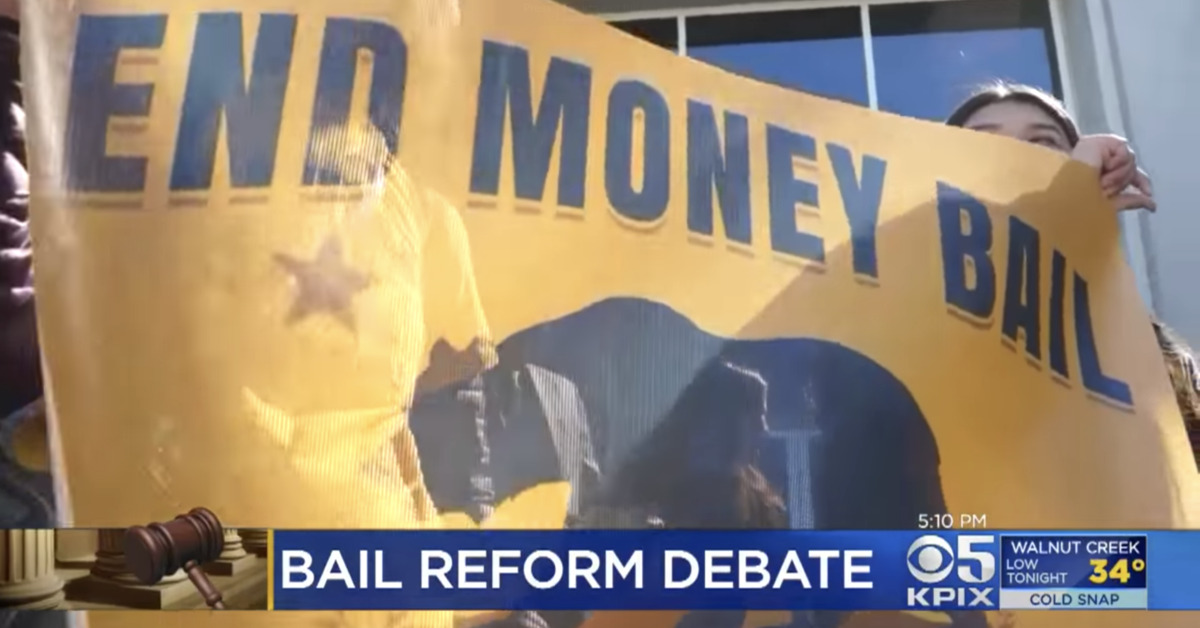

[image via screengrab/KPIX]