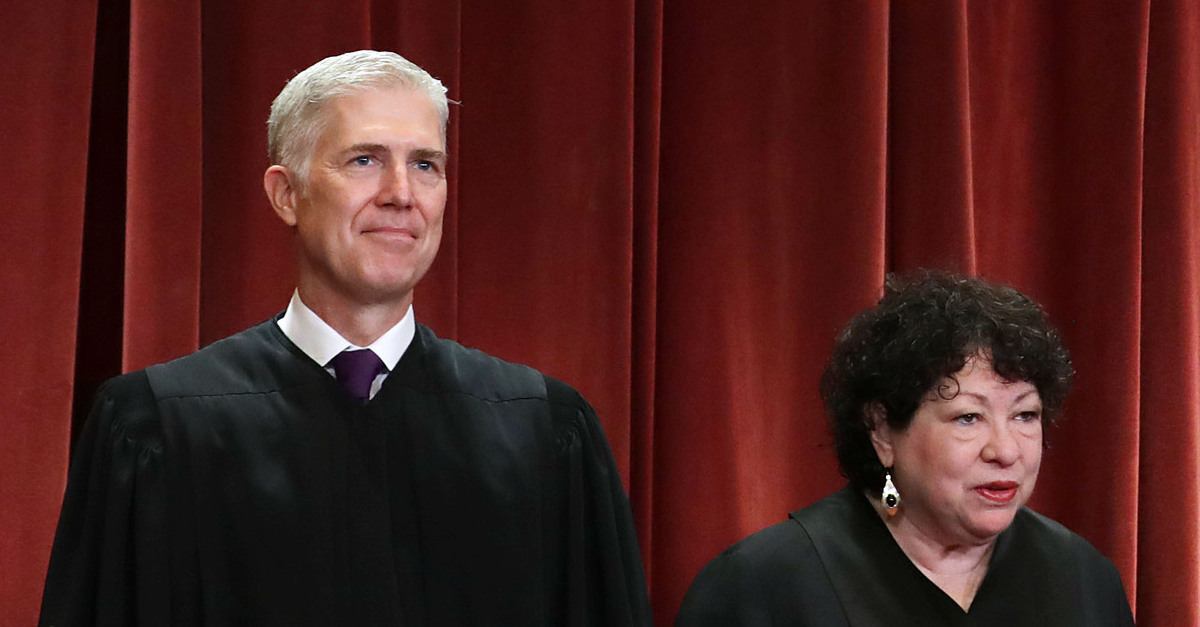

United States Supreme Court Justices Neil Gorsuch (L) and Sonia Sotomayor (R) pictured posing for an official court photo.

The Supreme Court on Monday unanimously held in favor of a criminal defendant who petitioned against a sentencing enhancement. In a concurrence, Justices Neil Gorsuch and Sonia Sotomayor said the court should have gone even further.

In Wooden v. United States, William Dale Wooden was facing a 15-year minimum sentence under a controversial and heavily-litigated law known as the Armed Career Criminal Act (ACCA) after being convicted of the federal prohibition against felons possessing guns.

The maximum sentence under the basic federal statute is 10 years in prison but the War on Drugs-era enhancement promises at least five additional years in prison for an offender convicted of violent crimes “committed on occasions different from one another.”

In 1997, Wooden and three others broke into a storage facility and went through a total of 10 different units by breaking the drywall between each one. They were eventually caught and the defendant was prosecuted in a single indictment, for 10 different counts of burglary, under Georgia law. Wooden pleaded guilty and was given 10 eight-year sentences which a judge allowed him to serve concurrently.

Justice Elena Kagan explains what led to the current dispute:

Fast forward now to a cold November morning in 2014, when Wooden responded to a police officer’s knock on his door. The officer asked to speak with Wooden’s wife. And noting the chill in the air, the officer asked if he could step inside, to stay warm. Wooden agreed. But his good deed did not go unpunished. Once admitted to the house, the officer spotted several guns. Knowing that Wooden was a felon, the officer placed him under arrest. A jury later convicted him for being a felon in possession of a firearm, in violation of 18 U. S. C. §922(g).

Initially, the government’s probation office recommended a relatively light sentence of 21 to 27 months in prison. They later changed course and moved to apply the ACCA–which necessitated at least 15 years in prison for possessing the guns in question. In the end, a district court judge sentenced Wooden to 188 months, or nearly 16 years in prison.

The defendant unsuccessfully argued before the district court, and later on appeal with the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, that his 10 burglaries were committed on one single occasion, rather than “on occasions different from one another.” The upshot of the argument, whether or not the ACCA should apply to his case or not, meant the difference between some 13 years behind bars.

Taking note of a circuit split on the issue, the nation’s high court decided to weigh in on the matter of the ACCA’s disputed “occasions” clause. And, in a fairly brief, barely-15-page opinion, the full court said Wooden’s night of burgling 10 separate storage units were, legally, crimes that were committed on one single occasion.

Kagan explains why this case was easy for the court:

Here, every relevant consideration shows that Wooden burglarized ten storage units on a single occasion, even though his criminal activity resulted in double-digit convictions. Wooden committed his burglaries on a single night, in a single uninterrupted course of conduct. The crimes all took place at one location, a one-building storage facility with one address. Each offense was essentially identical, and all were intertwined with the others. The burglaries were part and parcel of the same scheme, actuated by the same motive, and accomplished by the same means. Indeed, each burglary in some sense facilitated the next, as Wooden moved from unit to unit to unit, all in a row. And reflecting all these facts, Georgia law treated the burglaries as integrally connected. Because they “ar[ose] from the same conduct,” the prosecutor had to charge all ten in a single indictment

The opinion lays out a multi-factor test that aims to provide lower courts guidance in determining whether the ACCA applies. In his concurrence, Gorsuch complains the test offers “little guidance” but Kagan replies, in a footnote, that the test itself was supplied by Congress and that test was often being ignored in favor of a “categorical rule that sequential offenses always occur on different occasions”–a rule that all nine justices disagreed with. Notably, Sotomayor declined to join Gorsuch’s on his thoughts about the multi-factor test.

In concurring with the judgment, Gorsuch and Sotomayor agree that courts should be more willing to apply the doctrine known as “the rule of lenity” in cases that are not as “clear” or easy as Wooden’s.

“The ‘rule of lenity’ is a new name for an old idea—the notion that ‘penal laws should be construed strictly,'” the concurrence notes, before delving into a history of the doctrine and its specific use in the early American judicial system viz. “upholding the Constitution’s commitments to due process and the separation of powers.”

Over time though, Gorsuch notes, federal courts have picked away at the application of the doctrine and shied away from using lenity by creating various self-imposed hurdles.

The concurrence says that such limitations do “not derive from any well considered theory about lenity or the mainstream of this Court’s opinions,” and counsels that federal judges should be more willing to rule in criminal defendants’ favor when facing “ambiguous cases” in order to protect constitutionally-protected liberty interests.

“Where the traditional tools of statutory interpretation yield no clear answer, the judge’s next step isn’t to legislative history or the law’s unexpressed purposes.,” Gorsuch says. “The next step is to lenity.”

The reform-minded concurrence ends with a lengthy footnote that argues and portends a somewhat dire jury trial (and continued litigation) issue is lurking just below the logic of Kagan’s opinion.

Again, Gorsuch, at length:

A constitutional question simmers beneath the surface of today’s case. The Fifth and Sixth Amendments generally require the government in criminal cases to prove every fact essential to an individual’s punishment to a jury beyond a reasonable doubt. In this case, however, only judges found the facts relevant to Mr. Wooden’s punishment under the Occasions Clause, and they did so under only a preponderance of the evidence standard. Because Mr. Wooden did not raise a constitutional challenge to his sentence, the Court does not consider the propriety of this practice. But there is little doubt we will have to do so soon. And it is hard not to wonder: If a jury must find the facts supporting a punishment under the Occasions Clause beyond a reasonable doubt, how may judges impose a punishment without equal certainty about the law’s application to those facts?

[ERIN SCHAFF/POOL/AFP via Getty Images]