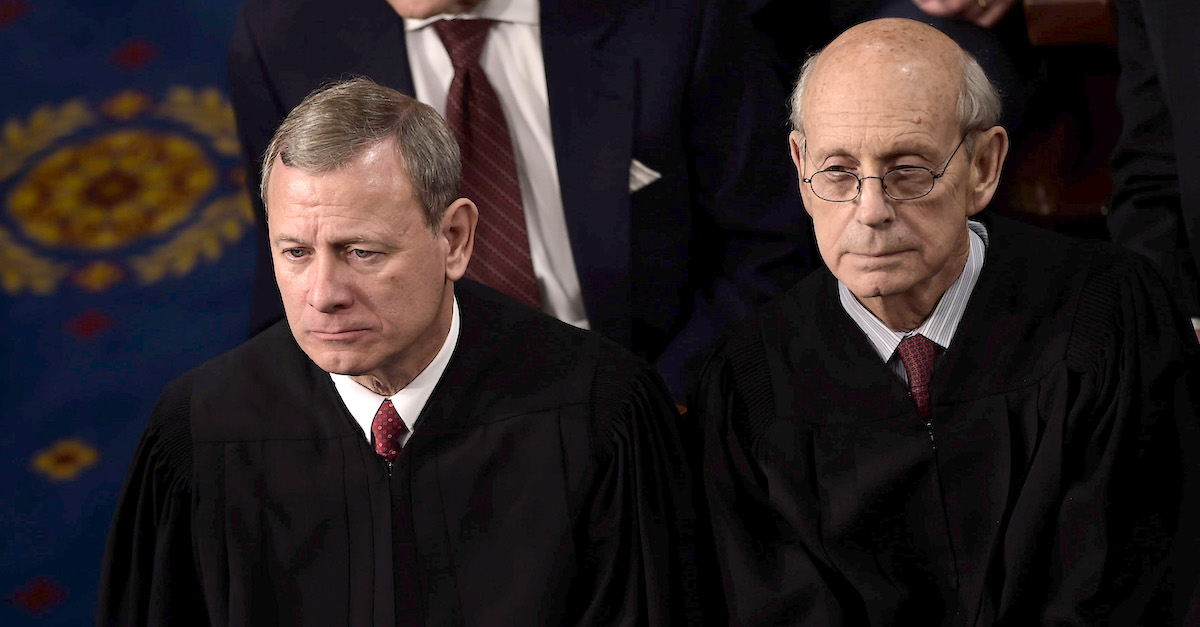

US Supreme Court Justices John G. Roberts Jr (L) and Stephen G. Breyer (R).

The Supreme Court of the United States ruled 6-3 on Thursday that Jane Cummings, a deaf and blind woman, is not entitled to damages for emotional distress based on being denied an American Sign Language (ASL) Interpreter by her physical therapy practice.

In the case, Cummings v. Premier Rehab Keller, P.L.L.C., Cummings argued that because Premier Rehab receives federal funding, it was legally obligated to accommodate her request under Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act and Section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act. Cummings contended that Premier Rehab’s refusal constituted “disability discrimination” for which she is entitled damages due to her resulting “humiliation, frustration, and emotional distress.”

Only the three justices in dissent, however, agreed that Cummings is entitled to the compensation she sought.

Chief Justice John Roberts authored the majority decision which was joined by Justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett. Justice Stephen Breyer penned a dissent which was joined by Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan.

In his 20-page opinion, Roberts was clear to point out that federal law outlaws discrimination based on protected grounds including disability status. What the law does not do, however, is allow individuals to wage private lawsuits for emotional distress damages as a remedy for discrimination. Roberts argued that the availability of remedies is tied directly to the an entity’s knowledge that its behavior might give rise to liability. Roberts wrote:

In order to decide whether emotional distress damages are available under the Spending Clause statutes we consider here, we therefore ask a simple question: Would a prospective funding recipient, at the time it “engaged in the process of deciding whether [to] accept” federal dollars, have been aware that it would face such liability? Arlington, 548 U. S., at 296. If yes, then emotional distress damages are available; if no, they are not.

The chief justice continued, explaining that funding recipients contract with the federal government, and under the usual “hornbook” tenets of contract law, neither punitive nor emotional distress damages are available as a remedy. Roberts argued that Cummings’ logic simply went too far, and “would treat funding recipients as on notice that they will face not only the usual remedies available in contract actions, but also other unusual, even ‘rare’ remedies.”

Roberts also responded to Cummings’ argument that some states do allow emotional distress damages in contracts claims under limited circumstances. The majority was unconvinced that a minority rule on the matter would be sufficient to justify the Supreme Court’s departure from well-settled contract law.

“As to which ‘highly unusual contracts’ trigger the exceptional allowance of such damages,” Roberts wrote, “the only area of agreement is that there is no agreement.”

Justice Kavanaugh penned a two-paragraph concurrence which was joined by Justice Gorsuch. Kavanaugh made the brief point that in his view, there is a separation-of-powers problem with Cummings’ claim. Accordingly, explained Kavanaugh, it is the job of “Congress, not this Court” to expand available remedies in the manner Cummings seeks.

Justice Breyer penned a 12-page dissent which was joined by Justices Sotomayor and Kagan. Breyer began with the argument that the kinds of invidious discrimination prohibited by statute “is particularly likely to cause serious emotional disturbance.” Breyer wrote that he agreed with the majority’s framework for answering the question at hand — but that he simply disagreed with the outcome.

“Damages for emotional suffering have long been available as remedies for suits in breach of contract—at least where the breach was particularly likely to cause suffering of that kind,” he wrote.

Breyer acknowledged that in most contracts cases, punitive or emotional distress damages are not available, but he reasoned that the purpose for the prohibition is that most contract breaches simply do not cause emotional damages.

“Most contracts are commercial contracts entered for pecuniary gain,” Breyer said. “Pecuniary remedies are therefore typically sufficient.”

By contrast, Breyer went on, commercial contracts (such as those for marriage, lodging, entertainment, handling of a body, or delivery of a telegram) do indeed give rise to emotional distress damages, “because they ‘make good the wrong done.'” In cases of discrimination, Breyer continued, “Often, emotional injury is the primary (sometimes the only) harm caused by discrimination, with pecuniary injury at most secondary.”

On the issue of whether funding recipients would be blindsided by emotional distress claims for actionable discrimination, Breyer noted that it would be “difficult to believe” that an entity like Premier Rehab would be unaware of such a risk. Breyer also dispensed with any analogy between the rules of punitive damages and those for emotional distress, writing, “unlike punitive damages, emotional distress damages can, and do, serve contract law’s central purpose of compensating the injured party for their expected losses.”

Breyer also had broader criticism for the Court’s majority. Its decision, said Breyer, “creates an anomaly,” in that other antidiscrimination statutes do allow emotional distress damages.

“It is difficult to square the Court’s holding with the basic purposes that antidiscrimination laws seek to serve,” wrote Breyer.

The retiring justice concluded with a warning about the potentially harmful effects of the majority’s ruling:

But the Court’s decision today allows victims of discrimination to recover damages only if they can prove that they have suffered economic harm, even though the primary harm inflicted by discrimination is rarely economic. Indeed, victims of intentional discrimination may sometimes suffer profound emotional injury without any attendant pecuniary harms. The Court’s decision today will leave those victims with no remedy at all.

[image via Brendan Smialowski/AFP via Getty Images]