A group of Michigan plaintiffs who worked with right-wing conspiracy attorneys Sidney Powell and Lin Wood in a failed attempt to keep ex-President Donald Trump in the White House is now seeking to avoid being sanctioned by a federal judge. The plaintiffs, who alleged massive voter fraud during 2020 election cycle, were part of the failed multi-jurisdiction litigation Powell dubbed the “Kraken.”

In federal court papers filed Tuesday in the Eastern District of Michigan, Stefanie Lambert Junttila, an attorney for the underlying election litigation plaintiffs, said that the City of Detroit—which intervened in the lawsuit—should not succeed in having the plaintiffs or their attorneys punished by the court because, among other reasons, several attorneys didn’t actually sign documents submitted to the court.

Lawyers for the city asked that a total of seven attorneys be sanctioned — even disbarred — because they were involved with the losing case.

“City’s motion must be denied as to all attorneys who did not actually appear or sign any pleadings in this matter,” the plaintiffs’ argument reads. It is rooted in Rule 11 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, which is one of several avenues available to courts to sanction or punish attorneys. Rule 11 currently states, in relevant part:

Every pleading, written motion, and other paper must be signed by at least one attorney of record in the attorney’s name—or by a party personally if the party is unrepresented.

[ . . . ]

The court must strike an unsigned paper unless the omission is promptly corrected after being called to the attorney’s or party’s attention.

Elsewhere, Rule 11 explains why signatures are important — and what they legally do and do not mean. The following emphasis on Rule 11’s language is ours, and it’s important:

By presenting to the court a pleading, written motion, or other paper—whether by signing, filing, submitting, or later advocating it—an attorney or unrepresented party certifies that to the best of the person’s knowledge, information, and belief, formed after an inquiry reasonable under the circumstances:

(1) it is not being presented for any improper purpose, such as to harass, cause unnecessary delay, or needlessly increase the cost of litigation;

(2) the claims, defenses, and other legal contentions are warranted by existing law or by a nonfrivolous argument for extending, modifying, or reversing existing law or for establishing new law;

(3) the factual contentions have evidentiary support or, if specifically so identified, will likely have evidentiary support after a reasonable opportunity for further investigation or discovery; and

(4) the denials of factual contentions are warranted on the evidence or, if specifically so identified, are reasonably based on belief or a lack of information.

The plaintiffs and their attorneys ignored that broad language to focus myopically on the practice of signing court papers and practicing before the court in general (legal citations omitted; bumpy grammar in original):

[T]he City’s motion must be denied as to all attorneys who did not actually appear or sign any pleadings in this matter. Rule 11 is concerned with the signing of frivolous pleadings and other papers. It may not be invoked against attorneys whose names appear on a pleading but who have not signed the pleading or otherwise formally appeared in the action.

Indeed, “[w]here plaintiff signed filed papers, but the attorney’s name appeared on papers only in typewritten form, sanctions cannot be imposed on attorney since Rule 11 focuses only on individual who signed document in question. Typewritten name is not signature for purpose of Rule 11, and therefore senior partner of law firm which represented defendants and whose name was typed on pleadings but who did not personally sign them is not subject to Rule 11 sanctions.

The arguments seemingly skirt an ethical reality: the signature is less important than the act of representation. Remember: under the modern version of Rule 11, the legal significance of the “signature” requirement also applies to filing, submitting, and advocating for a position. Even the cases cited by the plaintiffs suggest an argument that is evasive at best. The plaintiffs rely heavily on a 1991 case from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, Giebelhaus v. Spindrift Yachts, which predates the 1993 revision of Rule 11 which expands the “signature” requirement to involve advocacy, not just signatures. The cases the plaintiffs cited to support their signature-formality argument are dated 1986, 1987, 1990, 1991 — well before the 1993 revision expanded the ethical obligations of attorneys.

Rule 11 was altered in 1993 due in part due to the trickery contained in those old cases. (The old rule is contained here and here.)

Let’s unpack the situation a bit further by looking at who signed what documents and entered various appearances.

The plaintiffs claim that “[t]he only signator or appearance made in the short life of this case has been by Plaintiffs’ local counsel.” Elsewhere, they claim “neither Mr. Wood nor Ms. Powell was a signer to the pleadings.” They further said “no signer [of the lawsuit] was the author or instigator of [quarrelsome] media content” on Twitter.

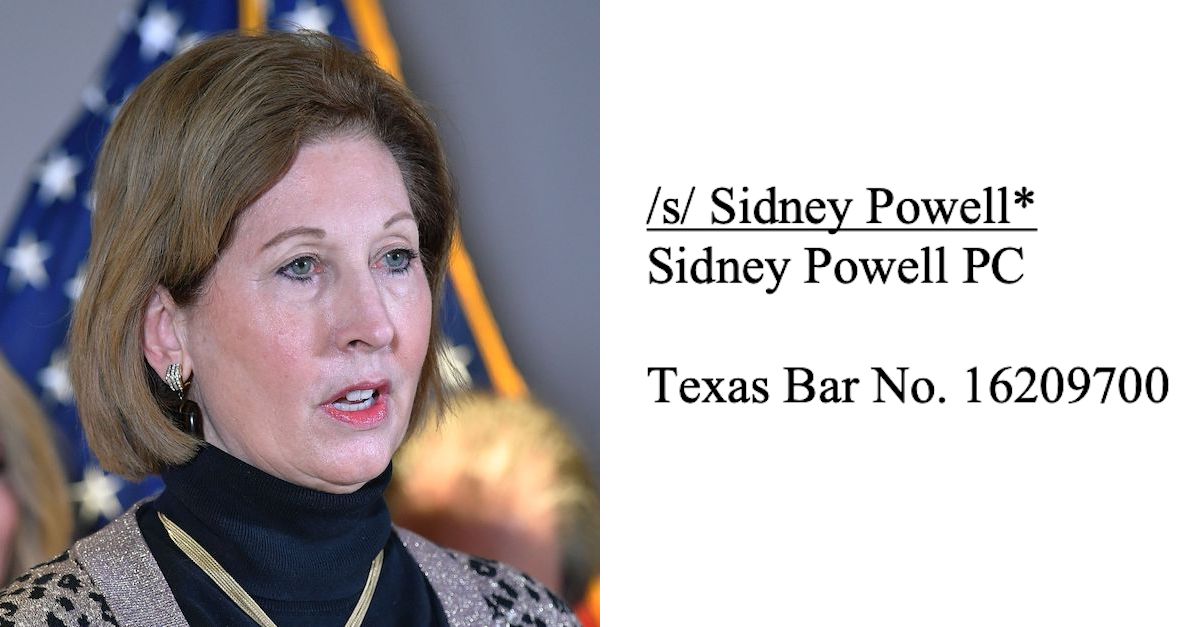

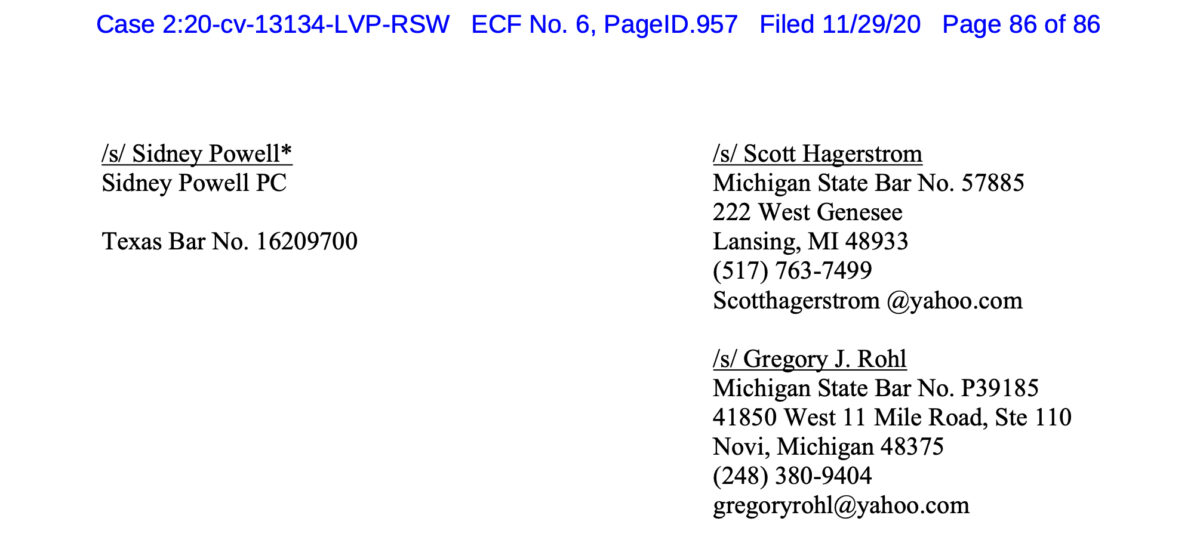

That is not entirely correct. Sidney Powell appears to have electronically signed a number of key documents. To wit, Powell’s name appears in the signature block of the initial complaint and a subsequent amended complaint filed shortly thereafter. Here’s a screenshot of the latter, with the case identifier in blue at the top of the page:

The asterisk after Powell’s name leads readers to the following footnote: “[a]pplication for admission pro hac vice [f]orthcoming.” In other words, Powell appears to have been planning to ask permission to file an appearance in the case without being a full member of the bar in the Eastern District of Michigan.

Five other attorneys are listed as being “of counsel” after the core three signatures above. Their names are Emily P. Newman, Julia Z. Haller, Brandon Johnson, Howard Kleinhendler, and — of course —Lin Wood.

Powell’s typed signature also appears on subsequent documents, such as a motion for a temporary restraining order and an emergency motion to seal documents. Her signature block does not appear in a Dec. 3 motion to extend deadlines, but it does appear on a motion that same exact day for an emergency temporary restraining order. It later appears on another emergency motion on Dec. 6.

Yet the plaintiffs said that “neither Mr. Wood nor Ms. Powell were signers to the pleading” and argued that the judge could not therefore use “their subjective beliefs” to determine whether the lawsuit was filed with an “improper purpose.”

Law&Crime reviewed many, but not all, of the plaintiffs’ documents in this case; Lin Wood did not appear to electronically sign any of them. Other so-called “local counsel” did, in addition to Powell.

Once considered questionable, electronic and “click-wrap” signatures are now commonplace in law, and the rules have changed to accommodate them.

The plaintiffs less than deftly pivoted their argument to involve the acts of officially advocating in a case.

“[T]here is no basis for this Court to apply Rule 11 sanctions to non-counsel of record,” the plaintiffs’ document argues. However, the claim was intertwined with the aforementioned signature issues:

The only signator or appearance made in the short life of this case has been by Plaintiffs’ local counsel. No other counsel signed any pleadings. Indeed, the City [of Detroit] recognizes that [local court rule] 83.20(a)(1) defines “practice in this court,” to include: “appear in, commence, conduct, prosecute, or defend the action or proceeding; appear in open court; sign a paper; participate in a pretrial conference; represent a client at a deposition; or otherwise practice in this court or before an officer of this court.” [Citation omitted.] None of that applies to any of Plaintiffs’ non-local counsel.

The plaintiffs quibbled over the technical definition of the “practice” of law but spent no time pointing out the rather shocking reality that neither Lin Wood nor Sidney Powell ever appeared to have entered formal pro hac vice appearances in the case. Neither Powell nor Wood appeared on a docketed list of attorneys handling the matter, and there is no record that Powell ever filed the pro hac paperwork promised by asterisk under several of her signature blocks. But the plaintiffs’ argument does not directly lay out that argument. It focuses narrowly on the signature issues (“neither Mr. Wood nor Ms. Powell was a signer to the pleadings”) ignores the broader issues involving “advocacy” as laid out in Rule 11, and ignores the lack of pro hac vice paperwork.

Elsewhere, the plaintiffs raised stronger claims involving dates. They argue that they voluntarily shut down their attempted election-busting litigation within Rule 11(c)(2)’s so-called “safe harbor” deadline and, thus, cannot be sanctioned. That Rule says, in relevant part, that sanctions motions “must not be filed or be presented to the court if the challenged . . . claim . . . is withdrawn or appropriately corrected within 21 days after service.” The plaintiffs say the defendants sent them an “anticipated” notice of sanctions on Dec. 15, but an official Rule 11 sanctions notice was not formally filed until Jan. 5. (A different sanctions motion under statutory law, 28 U.S.C. § 1927, was served Dec. 22.) The plaintiffs voluntarily shut down the litigation on Jan. 14. The time which elapsed between the official service on Jan. 5 and the voluntary shutdown on Jan 14 was nine days — well less than the 21 days contemplated by the Rule. The plaintiffs noted that “the ‘safe harbor’ period begins to run only upon service of the motion” (emphasis in original) and thus argued that they could not be penalized for filing a bogus case.

The plaintiffs more broadly claim that the City of Detroit, allies of the Joe Biden campaign, and their attorneys sought to smear the reputation of Lin Wood and Sidney Powell in an effort to save face. Court papers argue the city “tr[ied] to promote [the city’s] own agenda with the media and to distract from explosive evidence of voter fraud,” that the plaintiffs “had evidentiary support” for their claims, that the claims “were not frivolous,” and that the “plaintiffs had [a] reasonable basis” for filing their case. In the midst of these arguments, the plaintiffs levied a few serious slams and jabs against Detroit officials and their attorneys:

[T]he City begins its motion with language that claims Plaintiffs have “lied,” to this court. Such outrageous and unprofessional allegations are entirely unacceptable. The City cannot back up its absurd allegation. Proffering expert reports that are disputed by plaintiffs’ experts does not make counsel liars. And, if this were simply the ranting of a third rate five-man Detroit law firm, we would dismiss this behavior as pathetic unprofessionalism. But these are the dirty, media-attention hungry, slanderous and completely out-of-bounds statements by representatives of the City of Detroit. It should not be countenanced by this Court.

The plaintiffs further argue that “inartfully pled” claims — such as their election lawsuit — should not necessarily result in sanctions. Yet they also say their “factual allegations have not been ‘debunked'” and that they would have “provided adequate evidentiary support” had they been given a “reasonable opportunity for further investigation or discovery.”

The document goes on to spend considerable time boosting the same claims and witnesses already rubbished by other courts in all other jurisdictions. This time, the arguments weren’t about whether the case should be tried; rather, they were about whether it was so far afield to warrant sanctions.

Law&Crime reached out to Stefanie Lambert Junttila for comment; no response was received.

Read the plaintiffs’ arguments below:

Michigan Kraken Sanctions Response by Law&Crime on Scribd

[Image of Powell by MANDEL NGAN/AFP/Getty Images]