Justice Clarence Thomas’s legacy on the Supreme Court is uncertain. He has not written groundbreaking decisions, his reactionary jurisprudence often is too radical to gain many adherents on the Court, and his opinions dealing with race convey a sense of his bitterness at being seen as a beneficiary of affirmative action and a victim of false accusations of sexual misconduct during his Supreme Court confirmation hearing. Sometimes he demeans the Court, as he did last week in his dissenting opinion in a death penalty appeal, Flowers v. Mississippi, in which he accused the majority of taking the case “to boost its self-esteem” and “because the case has received a fair amount of media attention.”

The highly-publicized case centers on the conduct of a Mississippi prosecutor, Doug Evans, who engaged in an openly racist crusade over six separate jury trials, spanning 20 years, to convict Curtis Flowers, a black man, of a quadruple homicide. Evans, as the Mississippi appellate courts repeatedly found, engaged in numerous acts of misconduct in all of the trials. But Evans’s most egregious conduct was striking from the juries across the six trials 41 of 42 African-American jurors. Evans is reported to have kept one black juror from the last trial to protect himself from a charge of racial discrimination, or as the Supreme Court noted, “to obscure an otherwise consistent pattern of opposition to seating black jurors.” As the Mississippi state court in one of Evans’ prosecutions stated: “The instant case presents us with as strong a case of racial discrimination as we have ever seen.”

The case has been vividly dramatized in the podcast series In the Dark, but attracted more media attention because of a noteworthy event during the oral argument of the case in the Supreme Court. Justice Thomas, who is famous for never asking a question during oral argument, startled everybody in the courtroom with a question, his first question in three years, and his second in a decade. As the lawyer for Flowers was arguing that the prosecutor engaged in unconstitutional conduct in removing virtually every black juror from every trial, Justice Thomas suddenly interjected, asking the lawyer whether the defense counsel struck any jurors. When the lawyer answered yes, Justice Thomas asked “What was the race of the jurors?” Justice Thomas’s implication, of course, was that since both sides struck jurors, it resulted in a racially-balanced jury. But as the Court’s opinion pointed out, Justice Thomas’s “both-sides-can-do-it” argument overlooks the real world of criminal trials. With the black population at 12%, a prosecutor can eliminate all black jurors, as Evans did, but a black defendant can never eliminate all white jurors.

The Supreme Court, in a powerful 7-2 decision written by Justice Brett Kavanaugh, reversed Flowers’ conviction and death sentence. The Court found that Evans’ misconduct across the six trials was “extraordinary,” “blatant,” and evinced a “relentless effort to rid the jury of black individuals.” Evans supported his strikes, the Court added, by misrepresenting the record and falsifying the facts. The Court meticulously recounted how Evans through six trials removed every potential black juror and how his “dramatically disparate” questions to black and white prospective jurors was so “stark” as to be almost comical.

But it is the dissent of Justice Thomas that stands out. It’s a cruel and dishonest opinion. It’s cruel in the way Justice Thomas seeks to uphold the rectitude of a ruthless and unethical prosecutor. And it’s dishonest in the way Justice Thomas knowingly distorts the legal doctrine dealing with race discrimination in jury selection. To be sure, Justice Thomas, in his 42-page dissent, one of the longest opinions by any Justice this Term, assiduously pieces together snippets of dozens of questions by Evans to dozens of different jurors and their answers, to suggest that the prosecutor behaved properly and was consistent with constitutional requirements. Indeed, as Justice Thomas argued, Evans always gave “race-neutral” reasons for his strikes of black jurors. In fact, Justice Thomas repeats twenty-seven times in his dissent that Evans always gave “race-neutral” reasons. But, of course, as anyone familiar with the landmark case of Batson v. Kentucky well knows, prosecutors are forbidden under the Constitution’s equal protection clause to strike jurors because of their race, but when they do, they always give “race-neutral” reasons to defend their strikes. Does Justice Thomas believe that a prosecutor would stand up in court and proclaim: “I struck that juror because she was black”?

Prosecutors are well known to give all sorts of “race-neutral” reasons for ridding the jury of black individuals: “inattentive;” “body language;” “didn’t make no eye contact; “seemed insincere;” “a gut feeling;” “too old;” “too young;” “surname;” “long hair;” “goatee type beard;” “earring,” and so many, many more kinds of excuses. The critical question under Batson, as Justice Thomas well knows, is whether the prosecutor’s supposedly “race-neutral” reason is a cover–a pretext–for a racially-invidious motive. Sometimes, as in Flowers, a prosecutor’s true motive can be exposed simply by looking at the statistics: Evans struck 41 out of 42 black jurors during six trials, kept 71 white jurors instead. Is there any serious doubt that Evans’ striking from jury service 41 out of 42 black individuals was done for a reason other than their race?

Justice Thomas’s dissenting opinion in Flowers was cruel and dishonest. He finds blameless a bad prosecutor, distorts the record, perverts the legal analysis, chastises the Court for taking the case, attacks the media for promoting the case, and advocates dismantling the landmark Supreme Court precedent Batson v. Kentucky that has stood for a generation as a powerful protection for black defendants from racist prosecutors like Evans. Whatever Justice Thomas’s legacy, his opinion in Flowers should not be forgotten.

Professor Bennett Gershman is a Professor of Law at the Elisabeth Haub School of Law at Pace University, a former prosecutor in the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office, and a Special Assistant Attorney General in New York State’s Anti-Corruption Office.

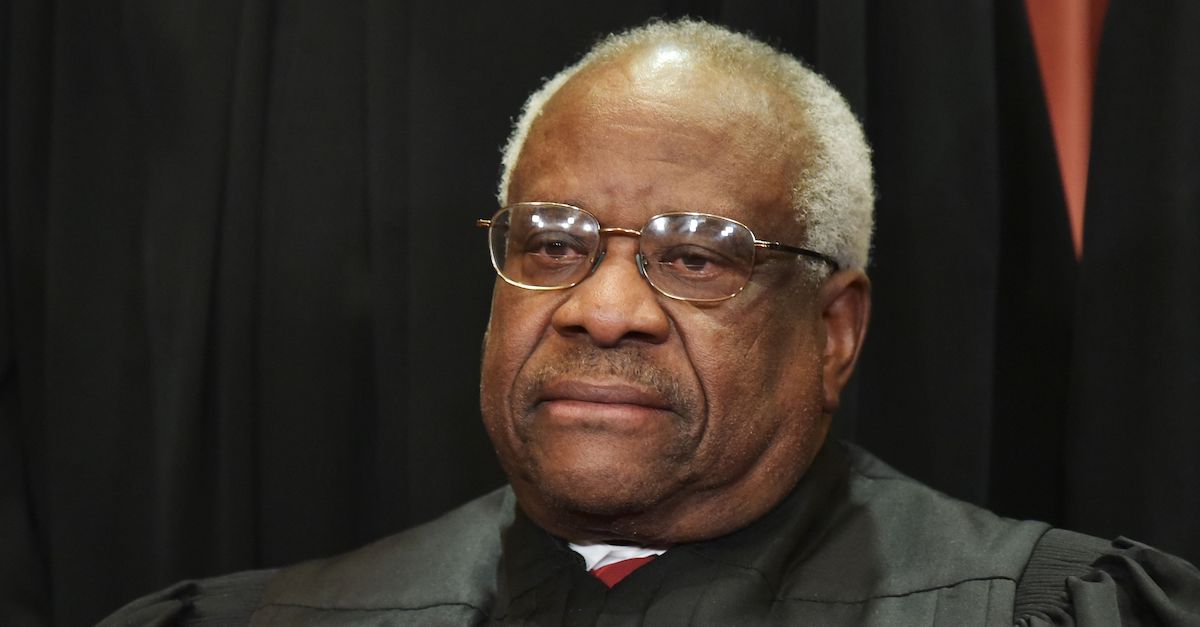

[Image via MANDEL NGAN/AFP/Getty Images]

This is an opinion piece. The views expressed in this article are those of just the author.