George Jarkesy. (Image via FOX Business/YouTube screengrab.)

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit on Wednesday issued a scathing 30-page opinion which excoriates administrative agencies in general and the Securities and Exchange Commission in particular.

The court’s 2-1 holding said that the SEC’s administrative proceedings against a right-wing talk show host, Republican donor, and hedge fund promoter accused of securities fraud violated at lest two separate clauses of the U.S. Constitution. It also said that the President of the United States should have more power to remove SEC judges from office. The upshot of the Fifth Circuit’s opinion was to vacate an SEC judgment that previously required the host, donor, and hedge fund promoter — whose political activities and media appearances were not mentioned or addressed in the opinion — to disgorge alleged “ill-gotten gains” and pay SEC-imposed fines — all of which totaled nearly a million dollars.

The majority analysis supported “limiting federal government power over crime” and bemoaned the effects of the “strong hand of the federal government.” Citations to English common law treatises, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and the Federalist Papers jockeyed with and perhaps even overwhelmed citations to actual case law and constitutional provisions in the majority opinion, though the latter were naturally part of the analysis.

The SEC accused George R. Jarkesy Jr. of having “worked closely with” another individual “to launch two hedge funds that raised $30 million from investors,” according to a 2013 press release. “Jarkesy and his firm John Thomas Capital Management (since renamed Patriot28 LLC) inflated valuations of the funds’ assets, causing the value of investors’ shares to be overstated and his management and incentive fees to be increased. Jarkesy, a frequent media commentator and radio talk show host, also lied to investors about the identity of the funds’ auditor and prime broker.”

Those accusations took a back seat in the Fifth Circuit’s opinion, which focused on the procedural question of whether the SEC wrongfully prosecuted Jarkesy.

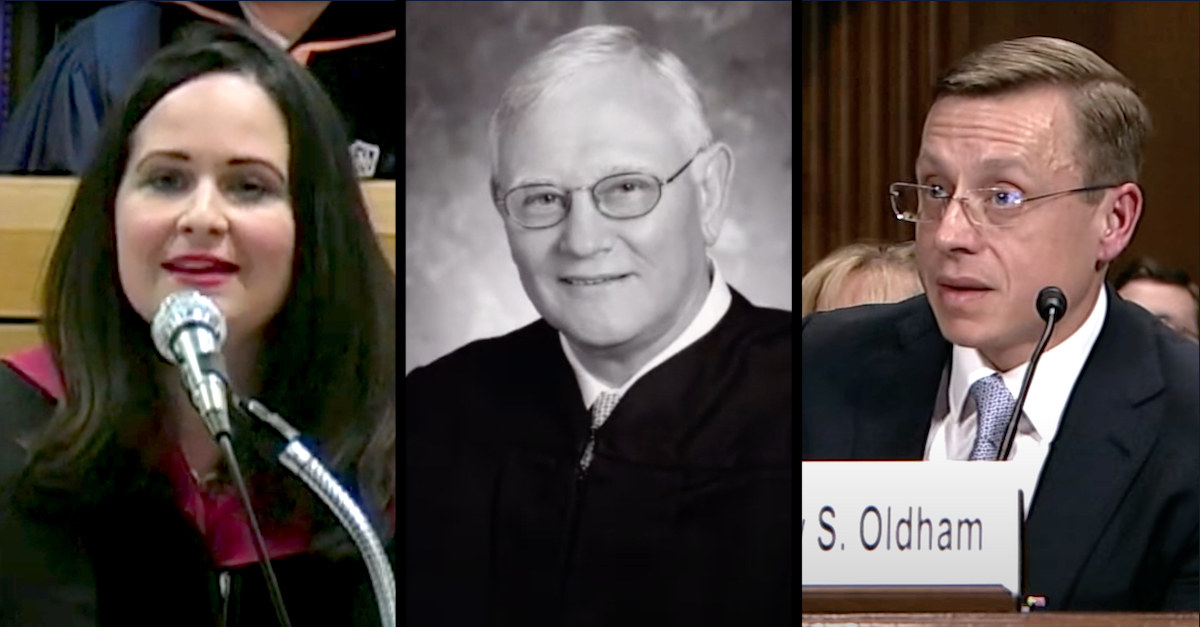

The three-member Fifth Circuit panel was composed of circuit judges W. Eugene Davis (a Ronald Reagan appointee), Jennifer Walker Elrod (a George W. Bush appointee), and Andrew Oldham (a Donald Trump appointee who used to be general counsel to Republican Texas Gov. Greg Abbott).

Elrod wrote for the court and was joined by Oldham; Davis dissented via a separate 24-page missive.

Judges Jennifer Walker Elrod, W. Eugene Davis, and Andrew Oldham.

Here is the introduction and the court’s holding:

Congress has given the Securities and Exchange Commission substantial power to enforce the nation’s securities laws. It often acts as both prosecutor and judge, and its decisions have broad consequences for personal liberty and property. But the Constitution constrains the SEC’s powers by protecting individual rights and the prerogatives of the other branches of government. This case is about the nature and extent of those constraints in securities fraud cases in which the SEC seeks penalties.

We hold that: (1) the SEC’s in-house adjudication of Petitioners’ case violated their Seventh Amendment right to a jury trial; (2) Congress unconstitutionally delegated legislative power to the SEC by failing to provide an intelligible principle by which the SEC would exercise the delegated power, in violation of Article I’s vesting of “all” legislative power in Congress; and (3) statutory removal restrictions on SEC ALJs violate the Take Care Clause of Article II. Because the agency proceedings below were unconstitutional, we GRANT the petition for review, VACATE the decision of the SEC, and REMAND for further proceedings consistent with this opinion.

Jarkesy “established two hedge funds and selected . . . Patriot28 as the investment adviser,” according to the opinion. (Earlier reports say Patriot28 was, indeed, Jarkesky’s company.) About 100 investors came into the fold, and $24 million in assets were eventually in the mix.

Both Jarkesy and Patriot 28 were petitioners in the case. The SEC accused the two (and some other “former co-parties”) of several alleged misdeeds and misrepresentations.

“Specifically, the agency charged that Petitioners: (1) misrepresented who served as the prime broker and as the auditor; (2) misrepresented the funds’ investment parameters and safeguards; and (3) overvalued the funds’ assets to increase the fees that they could charge investors,” the Fifth Circuit noted.

The petitioners tried to fight the SEC in the federal courts in Washington, D.C., and the case shuffled from the district court to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit without relief. The D.C. Circuit found that the district court didn’t have jurisdiction to hear the complaint and that the petitioners had to battle the SEC via its own administrative proceedings — and before its own internal judges — before taking the case to federal court.

It is a general legal axiom that parties must exhaust their administrative agency remedies before litigating in an actual federal court.

The SEC moved forward with its administrative law proceedings before an internal SEC administrative law judge, known as an ALJ for short. While the case was in situ at the SEC, the U.S. Supreme Court held that some SEC ALJs “had not been properly appointed under the Constitution,” the Fifth Circuit noted. The SEC then kicked the case to a properly appointed ALJ; the petitioners waived several rehearings and simply agreed to move along without a fuss.

Here’s how the Fifth Circuit summarized the upshot of those ALJ proceedings:

The Commission affirmed that Petitioners committed various forms of securities fraud. It ordered Petitioners to cease and desist from committing further violations and to pay a civil penalty of $300,000, and it ordered Patriot28 to disgorge nearly $685,000 in ill-gotten gains. The Commission also barred Jarkesy from various securities industry activities: associating with brokers, dealers, and advisers; offering penny stocks; and serving as an officer or director of an advisory board or as an investment adviser.

The petitioners then sought a review once again by the federal courts elsewhere. The Fifth Circuit, after reviewing the matter, agreed that several constitutional violations occurred.

“The Seventh Amendment guarantees Petitioners a jury trial because the SEC’s enforcement action is akin to traditional actions at law to which the jury-trial right attaches,” the court wrote. “And Congress, or an agency acting pursuant to congressional authorization, cannot assign the adjudication of such claims to an agency because such claims do not concern public rights alone.”

Specifically, the Fifth Circuit held that the core claims involved a form of “falsity or fraud” under the common law — yes, there are citations in the opinion to treatises about Old England — and therefore triggered the Seventh Amendment’s right to a jury trial.

“Securities fraud actions are not new actions unknown to the common law,” the majority wrote.

The opinion continued:

The Supreme Court has held that the Seventh Amendment applies to proceedings that involve a mix of legal and equitable claims—the facts relevant to the legal claims should be adjudicated by a jury, even if those facts relate to equitable claims too. (Citation omitted.) Here, the SEC sought to ban Jarkesy from participation in securities industry activities and to require Patriot28 to disgorge ill-gotten gains—both equitable remedies. Even so, the penalty facet of the action suffices for the jury-trial right to apply to an adjudication of the underlying facts supporting fraud liability.

Arguments by the SEC that its “securities statutes are designed to protect the public at large” and that its internal proceedings were designed to “vindicat[e] rights on behalf of the public” (in other words, protect investors) did not persuade the court.

Then came a lengthy tome from the majority about the court’s view of the proper role of government:

“We the People” are the fountainhead of all government power. Through the Constitution, the People delegated some of that power to the federal government so that it would protect rights and promote the common good. See The Federalist No. 10 (James Madison) (explaining that one of the defining features of a republic is “the delegation of the government . . . to a small number of citizens elected by the rest”). But, in keeping with the Founding principles that (1) men are not angels, and (2) “[a]mbition must be made to counteract ambition,” see The Federalist No. 51 (James Madison), the People did not vest all governmental power in one person or entity. It separated the power among the legislative, executive, and judicial branches. See The Federalist No. 47 (James Madison) (“The accumulation of all powers, legislative, executive, and judiciary, in the same hands, whether of one, a few, or many, and whether hereditary, self-appointed, or elective, may justly be pronounced the very definition of tyranny.”). The legislative power is the greatest of these powers, and, of course, it was given to Congress. U.S. Const. art. I, § 1.

The Constitution, in turn, provides strict rules to ensure that Congress exercises the legislative power in a way that comports with the People’s will. Every member of Congress is accountable to his or her constituents through regular popular elections. U.S. Const. art I, §§ 2, 3; id. amend. XVII, cl. 1. And a duly elected Congress may exercise the legislative power only through the assent of two separately constituted chambers (bicameralism) and the approval of the President (presentment). U.S. Const. art. I, § 7. This process, cumbersome though it may often seem to eager onlookers, ensures that the People can be heard and that their representatives have deliberated before the strong hand of the federal government raises to change the rights and responsibilities attendant to our public life. Cf. Rachel E. Barkow, Separation of Powers and the Criminal Law, 58 Stan. L. Rev. 989, 1017 (2006). (“[T]he Framers weighed the need for federal government efficiency against the potential for abuse and came out heavily in favor of limiting federal government power over crime.”).

The Fifth Circuit then criticized the inability of the president to swiftly remove ALJs with whom he might disagree — an interesting thought given the underlying political activities of Jarkesy (which, again, were not addressed in the opinion).

Along those lines, the court said “the President must have adequate power over officers’ appointment and removal.”

“Only then can the People, to whom the President is directly accountable, vicariously exercise authority over high-ranking executive officials,” the majority continued. “SEC ALJs are insulated from the President by at least two layers of for-cause protection from removal, which is unconstitutional.”

Judge Davis’s dissent suggested that ALJs needed sufficient protection from the political whims of the president in order to remain neutral initial arbiters of security law.

The majority quibbled with that dissent by citing Ronald Reagan’s famous “Nine Most Terrifying Words in the English Language” quote: “I’m from the Government, and I’m here to help.”

Before becoming a judge, Oldham once said that the “administrative state” was both “illegitimate” and “enraging,” noted Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-R.I.) during a confirmation hearing for then-nominee Oldham. Oldham defended himself by saying he was speaking on behalf of Abbott when he made the comments.

“Don’t kid me,” Whitehouse snapped back and pointed to the personal emotional tone of the comments.

“I am being quite serious when I say I was advocating on behalf of a client,” Oldham continued.

“Were you, then, enraged?” Whitehouse asked Oldman, referring to his personal feelings.

Oldham said he was “frustrated on behalf of my client” and said he would separate his client’s views from his “perspective as a jurist.”

Whitehouse said he had concerns about Oldham’s ability to “firewall” his views once he donned a judicial robe.

Read the full Fifth Circuit opinion — and the dissent — below:

[all images via YouTube screengrabs]