Aided by President Donald Trump, his campaign legal team, and right-wing political pundits, the post-election media landscape has been inundated with disinformation in an effort to sow doubt over President-elect Joe Biden’s win. The statuses of various lawsuits challenging the election results have been a particularly ripe target for such falsehoods, and Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton’s (R) long-shot Supreme Court lawsuit is the latest example of that.

Texas’s motion for leave to file a lawsuit, which seeks to have the justices throw out the election results in the states of Pennsylvania, Georgia, Michigan, and Wisconsin (all of which Trump lost), landed on the high court’s docket on Tuesday. Election law experts dismissed the lawsuit as nothing more than a stunt, albeit a “dangerous” one. But President Trump’s supporters seized on the simple fact that the justices are requiring the states to respond by Thursday as evidence that the court will actually hear—or has actually agreed to hear—the case. It is unlikely that the court will decide to hear the case and the court has not agreed to hear it.

First, despite gaining widespread traction among Trump supporters on Twitter and other social media platforms, there is no truth to the notion that the justices already voted 6-3 to hear Texas’s case.

Second, the court instructing the states being sued to file a response does not mean the justices will hear arguments on the merits of the action.

“Requiring the states to respond is not an indication that the justices plan on hearing the case. It’s an entirely routine move on the part of the Court, one that reflects a simple courtesy that I would have been surprised to see the Court omit,” Harvard Law professor emeritus and constitutional scholar Laurence Tribe told Law&Crime.

According to Tribe, who described the lawsuit as “completely frivolous,” the complaint should be dismissed for “failing to establish the standing of Texas to complain of any cognizable injury to the State in any of its various capacities: sovereign, quasi-sovereign, proprietary, or parens patriae on behalf of its citizens and voters.”

“The complaint articulates no coherent theory of how each Defendant State’s manner of appointing its electors, as approved by the judicial and executive authorities of that State, usurps the State Legislature’s authority or otherwise violates anything in that State’s constitution or the United States Constitution,” Tribe said. “None of the complaint’s theories of how the Defendant States supposedly violated the law match up with any distinct harm even alleged, much less shown, to be suffered by the State of Texas in any of its various capacities.”

Third, the invocations “original jurisdiction” are being misconstrued to suggest that the court has to hear the case. For example, White House Press Secretary Kayleigh McEnany tweeted on Tuesday that the state v. states lawsuit meant “Texas will have original jurisdiction to go directly to the Supreme Court!!”

“HUGE,” she said.

First, Texas does not have any jurisdiction in the matter. In lawsuits between two or more states, original jurisdiction is exclusive to the Supreme Court—meaning it is the only court that can adjudicate the matter. Second, this does not necessarily mean the justices are required to hear the case, as some assert—though Justices Clarence Thomas and Samuel Alito would and have disagreed on that point.

“Suffice it to say that no Justice could take the suit seriously,” Tribe said.

The court can—and likely will—just outright reject the case, as it did with Delaware’s 1966 election lawsuit against the state of New York.

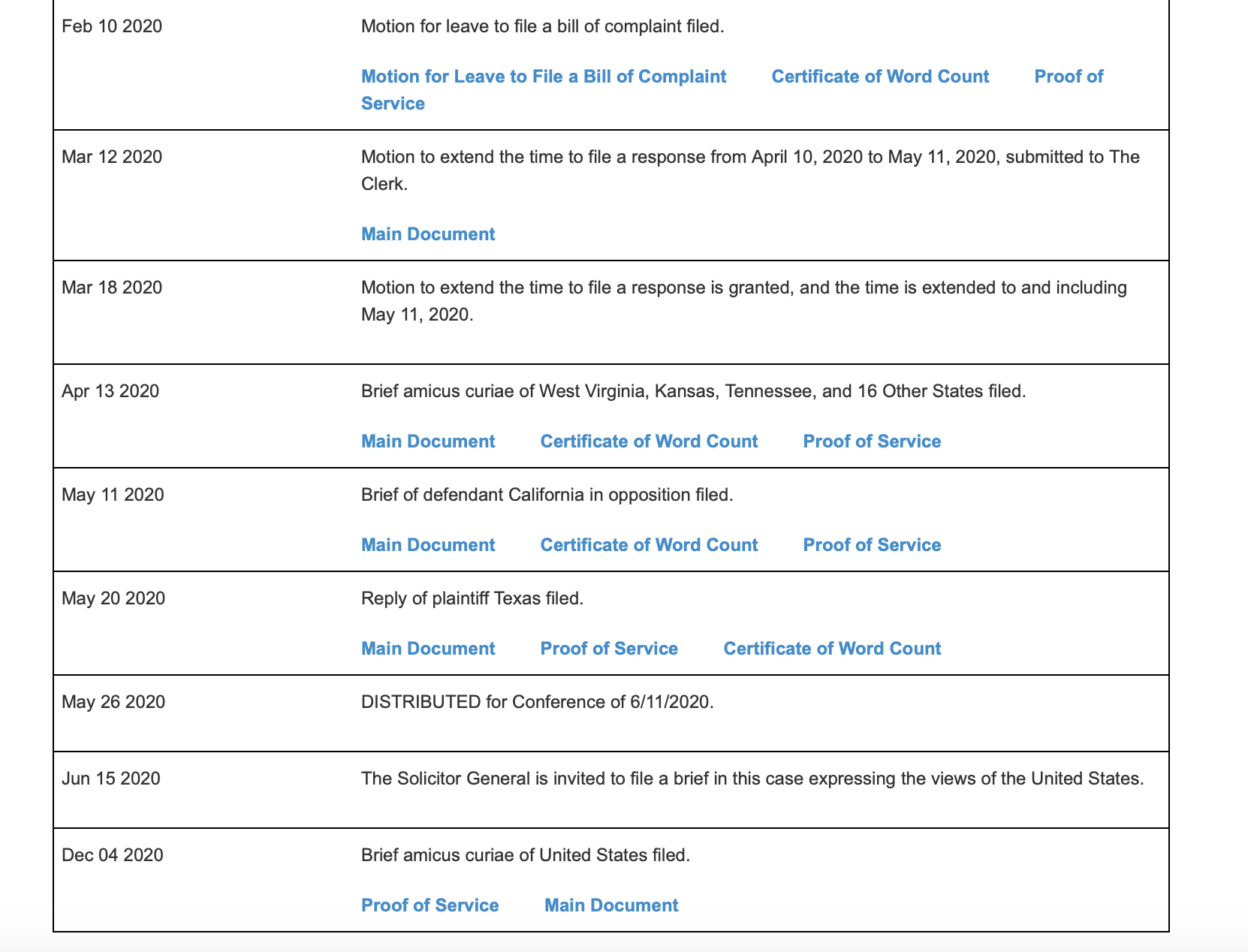

In fact, Texas filed a motion for leave to file a different state v. state action at SCOTUS as recently as Feb. That request for leave to sue California is still pending, as Reuters legal journalist Brad Heath noted.

“[T]he Supreme Court asked the other states to file a response by Thursday to Texas’ motion for leave to file its complaint. Doesn’t mean the court will act quickly. Texas’ request for leave to sue California has been pending since February,” Heath said. “Doesn’t mean the court won’t act quickly. It denied Rep. Kelly’s motion for an injunction minutes after getting his reply brief. But 3 p.m. is the deadline for state responses, not for the court to act.”

If you look at the docket of the Texas v. California case from February, you’ll see that some briefs have been submitted. But you will not see that the Supreme Court has acted on the motion for leave to file the bill of complaint. Ten months have passed.

That may not be the case here, but do not take a Thursday deadline for state responses as proof that SCOTUS has or will grant the motion for leave to file the bill of complaint.

Among those confused about the application of original jurisdiction is President Trump. On Wednesday, the president tweeted that “We will be INTERVENING in the Texas (plus many other states) case,” revealing that he was unaware that the intervention of a non-state party in the case would undermine the effort.

“The central purpose of #SCOTUS’s ‘original’ jurisdiction is for disputes between states that can’t be resolved elsewhere,” University of Texas law professor Steve Vladeck wrote. “Successful intervention by another party would prove that the dispute *could* be resolved elsewhere — and that there’s nothing unique about Texas’s claims.”

Regardless of the technical issues at play, even if the justices heard arguments, there’s virtually no chance Texas would be successful in its effort to overturn the election with such a poorly argued complaint, according to Tribe:

The complaint is riddled with ridiculous attempts to substitute funny math for actual analysis – as in its allegation that the ‘probability of former Vice President Biden winning the popular vote in the four Defendant States . . . independently given President Trump’s early lead in those States as of 3 a.m. on November 4, 2020, is less than one in a quadrillion,’ and that the odds of ‘that event happening [in all four States collectively] decrease to less than one in a quadrillion to the fourth power.’ Balderdash!

Beyond that, the complaint is filled with internal legal errors that undermine any theory it might otherwise be understood to advance. For instance, the complaint repeatedly treats 3 U.S.C. §7, governing the meeting of electors on the first Monday after the second Wednesday in December ‘following their appointment’ (December 14, this year) as though it provided ‘that presidential electors be appointed on December 14, 2020.’ I could go on indefinitely about how ridiculous the complaint is and how meritless and unthinkable is its requested remedy, but I’ll stop here.

[image via ANDREW CABALLERO-REYNOLDS_AFP via Getty Images]