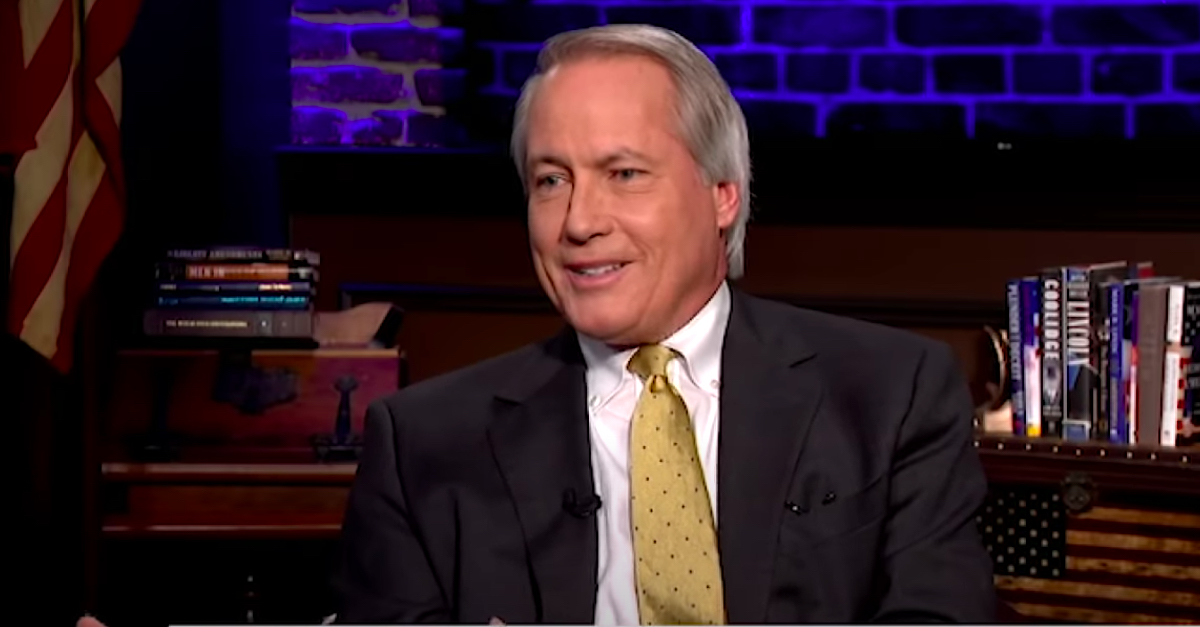

Attorney L. Lin Wood

Celebrity attorney L. Lin Wood lost another round in federal court on Saturday as a panel of judges affirmed a prior rejection of his efforts to overturn the 2020 election results in his home state of Georgia.

In late November, a district judge appointed by President Donald Trump rejected the right-wing lawyer’s bid for a temporary restraining order that would have halted vote certification in the Peach State.

Saturday’s 20-page ruling by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit affirms that lower court’s prior order.

“After Wood moved for emergency relief, the district court denied his motion,” the opinion by George W. Bush-appointed Chief Circuit Judge William Pryor explains. “We agree with the district court that Wood lacks standing to sue because he fails to allege a particularized injury. And because Georgia has already certified its election results and its slate of presidential electors, Wood’s requests for emergency relief are moot to the extent they concern the 2020 election. The Constitution makes clear that federal courts are courts of limited jurisdiction; we may not entertain post-election contests about garden-variety issues of vote counting and misconduct that may properly be filed in state courts.”

Wood’s novel lawsuit was premised on the idea that he had standing as an individual voter to allege that Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger (R) caused him irreparable harm by agreeing to a settlement agreement regarding signature matching on mail-in ballots in March. Eight months and several election cycles later, including the one in which Joe Biden narrowly but decisively defeated the incumbent president, Wood decided to sue.

But Wood’s lawsuit was simultaneously, too little, too late, and too much for the federal courts to stomach.

“His undue delay prejudiced the Secretary of State and certainly prejudiced the millions of voters in this election,” Trump-appointed U.S. District Judge Steven Grimberg declared at the time. “To halt the certification at literally the 11th hour would breed confusion and disenfranchisement that I find have no basis in fact and law.”

Undeterred, Wood appealed, though it was fairly obvious that his effort was not likely to fare much better.

Just before Thanksgiving, the 11th Circuit quizzed the lawyer about whether the court even had jurisdiction to hear the case. A series of queries concerning precedent strongly suggested the appeals court was skeptical that Wood’s complaints rose to the constitutional requirement that judges hear actual “cases” and “controversies.”

And in the end, those questions presaged the outcome here.

“When someone sues in federal court, he bears the burden of proving that his suit falls within our jurisdiction,” Pryor’s discussion notes. “Wood had the choice to sue in state or federal court. Georgia law makes clear that post-election litigation may proceed in a state court. But Wood chose to sue in federal court. In doing so, he had to prove that his suit presents a justiciable controversy under Article III of the Constitution. He failed to satisfy this burden.”

The opinion continues and explains exactly why Wood’s long-shot lawsuit was never going anywhere in the first place:

Wood lacks standing because he fails to allege the “first and foremost of standing’s three elements”: an injury in fact. An injury in fact is “an invasion of a legally protected interest that is both concrete and particularized and actual or imminent, not conjectural or hypothetical.” Wood’s injury is not particularized.

Wood asserts only a generalized grievance. A particularized injury is one that “affect[s] the plaintiff in a personal and individual way.” For example, if Wood were a political candidate harmed by the recount, he would satisfy this requirement because he could assert a personal, distinct injury. But Wood bases his standing on his interest in “ensur[ing that] . . . only lawful ballots are counted.” An injury to the right “to require that the government be administered according to the law” is a generalized grievance. And the Supreme Court has made clear that a generalized grievance, “no matter how sincere,” cannot support standing.

Regardless of the standing and jurisdictional issues, the court also noted that Wood’s complaint is now moot because Georgia certified its election results on November 20th.

“Because Georgia has already certified its results, Wood’s requests to delay certification and commence a new recount are moot,” Judge Pryor explained. “And it is not possible for us to delay certification nor meaningful to order a new recount when the results are already final and certified.”

The court also upbraided Wood over his understanding of the law:

Wood’s arguments reflect a basic misunderstanding of what mootness is. He argues that the certification does not moot anything “because this litigation is ongoing” and he remains injured. But mootness concerns the availability of relief, not the existence of a lawsuit or an injury. So even if post-election litigation is not always mooted by certification, Wood’s particular requests are moot. Wood is right that certification does not moot his requests for relief concerning the 2021 runoff—although Wood’s lack of standing still forecloses our consideration of those requests—but the pendency of other claims for relief cannot rescue the otherwise moot claims. Wood finally tells us that President Trump has also requested a recount, but that fact is irrelevant to whether Wood’s requests remain live.

Law&Crime reached out to Wood for comment and clarification but no response was forthcoming at the time of publication.

Read the full and brutal ruling below:

[image via screengrab/Fox News]

Editor’s note: this article has been amended post-publication for clarity and to include an additional link.