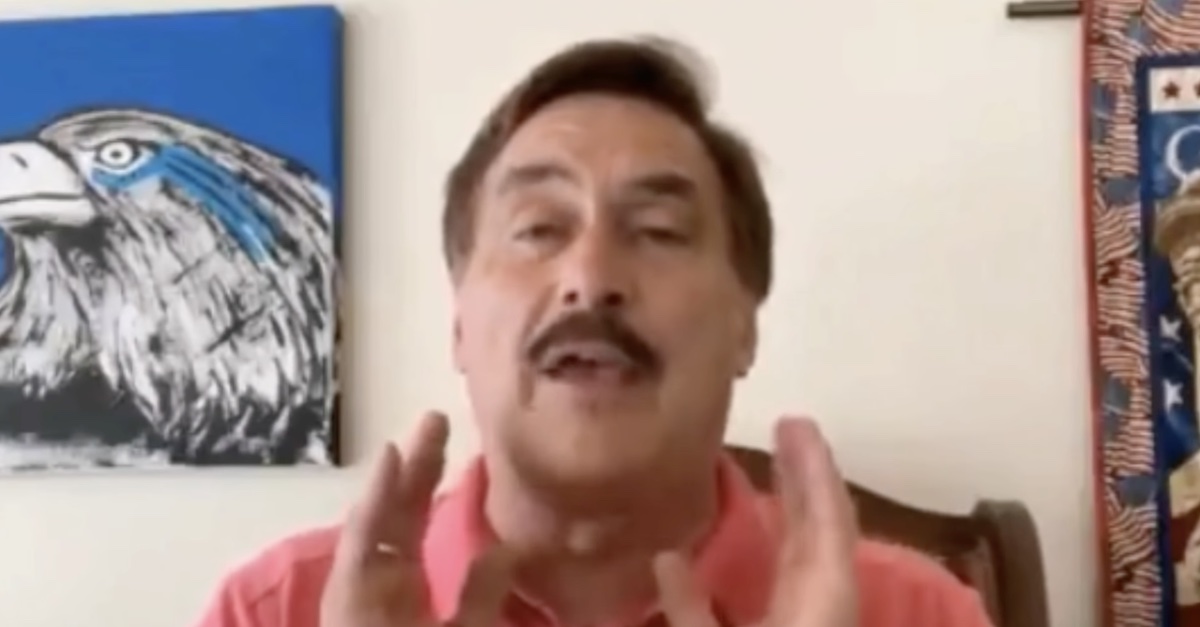

Mike Lindell. (Image via YouTube screengrab.)

A federal judge appointed by Donald Trump on Thursday dismissed a collection of counterclaims asserted by MyPillow and its Trump-supporting CEO Mike Lindell against voting technology companies US Dominion and Smartmatic.

The case originated when, in 2021, Dominion filed defamation lawsuits against Sidney Powell, Rudy Giuliani, and both Lindell and MyPillow for their respective comments about the 2020 election. Lindell moved to dismiss the case. A judge refused to acquiesce, and an appeals court affirmed the refusal. The trial court asked Lindell and MyPillow to file as counterclaims some of the arguments both the CEO and his company pressed against the two voting technology companies in separate lawsuits; both did as ordered.

“Dominion seeks to intimidate those who might dare to come forward with evidence of election fraud, stop criticism of election voting machines, and suppress information about how its machines have been hacked in American elections,” one of the Lindell counterclaims asserted.

“Dominion’s exaggerated lawsuits . . . are not about any damages it has suffered; they are designed to intimidate those who exercise their right to free speech about the election,” Lindell also insinuated.

Per the court, Lindell asserted eight counterclaims against Dominion:

(1) abuse of process,

(2) defamation,

(3) civil conspiracy,

(4) violations of the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organization Act of 18 U.S.C. § 1962 (better known as RICO),

(5) violations of the Support or Advocacy Clause of 42 U.S.C. §1985(3), and under 42 U.S.C. § 1983,

(6) violations of the Fourteenth Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause,

(7) violations of the Fourteenth Amendment’s Due Process Clause, and

(8) unlawful retaliation and viewpoint discrimination under the First Amendment.

MyPillow asserted five not dissimilar counterclaims against Dominion.

Lindell further filed a so-called “third-party complaint” — the procedural posture of which was contested — against Smartmatic. Via six separate causes of action, the complaint accused that company of having “weaponized the court system and the litigation process in an attempt to silence Lindell’s and others’ political speech about election fraud and the role of electronic voting machines in it.”

Those counterclaims and the “third-party” complaint have now been jettisoned from the docket.

For instance, Lindell’s “abuse of process” claim could be satisfied by the fact that one voting company merely filed a lawsuit against Lindell, Trump-appointed U.S. District Judge Carl J. Nichols ruled from Washington, D.C.

Mike Lindell, the founder of My Pillow, speaks with Donald Trump during an event with U.S. manufacturers in the East Room of the White House on July 19, 2017. (Photo by SAUL LOEB/AFP via Getty Images.)

After an analysis, the systematic takedown by Judge Nichols moved to its next point.

“Lindell’s RICO claim against Smartmatic fails because he fails to allege that Smartmatic shared the requisite common purpose with Dominion or other members of the alleged RICO enterprise,” the judge wrote.

He continued (citations and parentheticals are herein omitted):

Lindell alleges no fact raising an inference that Smartmatic worked with Dominion (or anyone else for that matter) “to pursue by common, coordinated efforts what they could not do on their own.” He also does not allege that Smartmatic communicated, met, or otherwise coordinated with Dominion or Hamilton Place [its public relations firm] in furtherance of their supposed “suppressive” aims. In short, Lindell offers no allegations from which to infer a “continuing unit that functions with a common purpose.”

“[T]he corporate history between Dominion and Smartmatic in no way suggests that the two companies ‘joined together’ to achieve an alleged illegal purpose,” the judge continued. “And Lindell’s Complaint contains no allegation that Dominion and Smartmatic did anything to coordinate their supposedly illegal ‘lawfare’ campaign.”

The judge said that the law was flatly against Lindell’s RICO claims (again, citations omitted):

Plaintiffs “may not plead the existence of a RICO enterprise between a corporate defendant and its agents or employees acting within the scope of their roles for the corporation because a corporation necessarily acts through its agents and employees.” As courts have repeatedly recognized, a contrary rule would make little sense, because if a corporate defendant were to face RICO liability “for participating in an enterprise comprised only of its agents,” then RICO liability “will attach to any act of corporate wrong-doing and the statute’s distinctness requirement” between the “person” and the “enterprise” would be “rendered meaningless.”

The Support or Advocacy Clause arguments also failed, the judge ruled, because Lindell failed to prove a key element of the supposed offense.

“Lindell fails to adequately allege an agreement,” the judge wrote. “Lindell’s Complaint points to no event, no conversation, no document—really, nothing at all—to suggest that Dominion, Smartmatic, or Hamilton Place reached any sort of ‘agreement.’ (Citations omitted.) Nor does Lindell offer allegations from which an agreement could be inferred.”

But there is a term for what Lindell did allege — a term that granted him no relief.

“At best, Lindell alleges that Dominion and Smartmatic engaged in ‘parallel conduct,'” the judge opined. “But parallel conduct, without more, does not adequately allege a conspiratorial agreement.”

The civil conspiracy claims also failed for reasons similar to those above, the judge ruled, because Lindell did not prove an “agreement.”

“At best, Lindell claims that Dominion and Smartmatic shared the ‘common goal’ of holding actors like Lindell accountable for allegedly defamatory statements,” the judge wrote. “That is not enough.”

“Indeed, until this case, ‘Lindell and Smartmatic had never been parties to the same litigation or had any communication with one another,'” the judge elsewhere noted while citing Smartmatic’s attestations about itself.

Rather, the judge said most of Lindell’s assertions were “wholly conclusory allegations unsupported by any alleged facts” and did not contain the requisite proof needed for a successful lawsuit.

The judge also tossed Lindell’s defamation claims against Dominion.

“Dominion called [Lindell] a ‘liar’ and . . . the purveyor of ‘the Big Lie,'” the judge noted. But those claims, the judge said, were protected by a privilege which attaches to litigation: “even Lindell admits that Dominion made the allegedly defamatory statements ‘in the D.C. Lawsuit.'”

After rubbishing Lindell’s claims one by one in systematic fashion, the judge turned to Smartmatic’s matter of sanctions against Lindell and his former attorneys. The judge said he would “in part” grant the voting technology company’s motion for penalties.

“The Court agrees with Smartmatic that Lindell has asserted at least some groundless claims,” the judge ruled. “In particular, the Court concludes that at the very least Lindell’s claim against Smartmatic under the Support or Advocacy Clause falls on the frivolous side of the line (other claims do too).”

The final amount of such sanctions, the judge said, would be determined after additional briefing. The concomitant briefs must not exceed ten pages, the judge said.

When reached for comment by Bloomberg, Lindell said he wasn’t sure if he would appeal the district court judge’s decision because he was too busy fighting the planned use of Dominion and Smartmatic machines in upcoming elections nationwide.

“Whatever the judge thinks, that’s his opinion,” Lindell told Bloomberg. “I’ve got lawyers doing more important things like removing these machines from every state.”

Read the judge’s full opinion — which more thoroughly delves into some of the rationale for the across-the-board dismissal — below:

[This piece has been updated to contain Lindell’s comments to Bloomberg.]

[Images as noted.]