Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito has asked Pennsylvania officials to file response briefs in a so-far-failed attempt by GOP Congressman Mike Kelly to flip Pennsylvania’s 2020 election results. Kelly, a loyal and longtime supporter of President Donald Trump, is asking the nation’s highest court to take up the same elections case the Pennsylvania Supreme Court summarily ejected with prejudice last weekend. Kelly’s 50-page application and 213-page appendix was submitted to Alito because he is the justice who oversees incoming matters from the Third Circuit, which includes Pennsylvania.

Though Alito originally called for response arguments from the Commonwealth to be filed by 4 p.m. on Wednesday, Dec. 9th, the case docket was changed Sunday morning to move that deadline up to Tuesday, Dec. 8, by 9 a.m. The change is critical. Pennsylvania’s members of the electoral college are due to meet at noon on Dec. 14th in Harrisburg to cast their votes for president. As Law&Crime has previously reported, and as Kelly’s arguments point out, federal election law sets a so-called “safe harbor” deadline which requires controversies “concerning the appointment of all or any of the electors . . . by judicial or other methods or procedures” to be determined “at least six days before the time fixed for the meeting of the electors.” Alito’s original Dec. 9th deadline failed to take that window into account. His new deadline does.

The thrust of Kelly’s arguments is that a 2019 state election reform statute known as Act 77 violated both the state constitution and the federal constitution. Act 77, which predates the coronavirus pandemic, was described when signed into law as a “bipartisan compromise.” It created a so-called “no-excuse mail-in” voting regime that Kelly claims violates a provision of the state constitution. Kelly interprets the constitution as allowing only limited circumstances which qualify a voter to cast a ballot by mail. In other words, in Kelly’s view, people must vote in person unless they can take advantage of only a few, narrow excuses contained within the state constitution and, therefore, Act 77 and related election access laws must be struck down as invalid. Because the 2020 election was conducted under Act 77, its results are questionable, he claims.

In strict theory, the U.S. Supreme Court has no jurisdiction to settle Pennsylvania constitutional issues, such as whether the state statute at question (Act 77) violates the state constitution. Generally, such matters are the exclusive realm of a state supreme court. But there are exceptions to that general concept, Kelly argues, including here. Because the state is acting under a “direct grant of authority” from the U.S. Constitution to manage federal elections, the U.S. Supreme Court can become involved, he argues, and can determine whether the Pennsylvania statutory and constitutional regime of laws violates the U.S. Constitution. Kelly invites the U.S. Supreme Court to conclude as such and, perhaps more dubiously, that the state court’s way of rubbishing the election violates his rights to petition the government and to receive due process under the First and Fourteenth Amendments thereto. He frames the issues this way:

1. Do the Elections and Electors Clauses of the United States Constitution permit Pennsylvania to violate its state constitution’s restrictions on its lawmaking power when enacting legislation for the conduct of federal elections?

2. Do the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution permit the dismissal of Petitioners’ claims with prejudice, on the basis of laches, where doing so foreclosed any opportunity for Petitioners to seek retrospective and prospective relief for ongoing constitutional violations?

The “elections clause” of the U.S. Constitution is Article I, § 4, clause 1. This clause basically says state legislatures can set their own rules for elections:

The Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof; but Congress may at any time make or alter such Regulations, except as to the Place of chusing Senators.

The U.S. Supreme Court has said the framers intended the clause as “a grant of authority to issue procedural regulations, and not as a source of power to dictate electoral outcomes, to favor or disfavor a class of candidates, or to evade important constitutional restraints.” (Naturally, many of Trump’s supporters are attempting to do the opposite of that.)

The “electors clause” is Article II, § 1, clause 2. This clause says that state legislatures “may direct” the “manner” by which “[e]ach state shall appoint” electors to the Electoral College.

“Pennsylvania’s General Assembly exceeded its powers by unconstitutionally allowing no-excuse absentee voting, including for federal offices, in the Election,” Kelly’s attorney wrote to Justice Alito. “The opinion below forecloses any means of remedying Petitioners’ injuries.”

“With respect to elections for federal office, both state legislatures and the Congress have specified roles inscribed in the Constitution as fail-safes for state failures in conducting elections,” the application to Justice Alito further argued.

The state supreme court punted the matter by holding that Kelly should have raised it earlier, e.g., after the law was passed, and certainly not after his preferred presidential candidate lost the election. The legal doctrine the state supreme court applied — laches — is a legal version of the phrase “speak now, or forever hold your piece.” Because Kelly didn’t sue immediately before or after the election, the court said it didn’t have to listen to his arguments or even consider whether they were valid.

“At least with respect to federal elections, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court was not free to deny the Petitioners any practical means of remedying their injuries that were caused by the Pennsylvania General Assembly implementing no-excuse absentee balloting in Pennsylvania by means of a statute rather than a Pennsylvania Constitutional amendment,” Kelly argues. “A fundamental requirement of due process is ‘the opportunity to be heard.'”

Kelly is asking for a writ of injunction to prevent various Pennsylvania state officials from from “taking any further action to perfect the certification of the results of the November 3, 2020, General Election (the Election’) in Pennsylvania for the offices of President and Vice President of the United States of America or certifying the remaining results of the Election for U.S. Senators and Representatives.” In the alternative, Kelly is asking the U.S. Supreme Court to stay the Pennsylvania Supreme Court’s proceedings. He’s also asking the U.S. Supreme Court to grant certiorari on the underlying merits of the case and to issue a decision to settle the core issues.

Kelly v. Commonwealth – SCOTUS Application by Law&Crime on Scribd

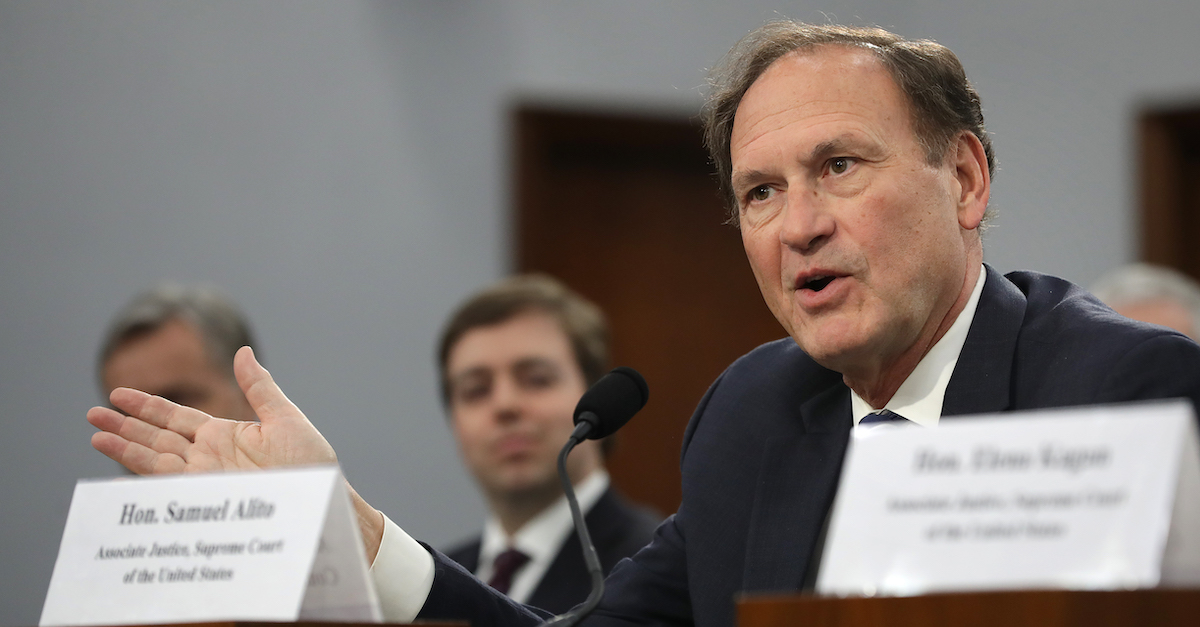

[File photo by Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images]

Editor’s note: this report has been updated to reflect Sunday morning’s deadline changes for the Commonwealth’s response.