Two voters have filed a federal lawsuit against the state of California over its upcoming recall election to oust Democratic Governor Gavin Newsom. Their argument? That California’s recall process violates the equal protection clause of the United States Constitution. The plaintiffs hope to stop — or at least change — the election to recall Newsom, which will conclude on September 14, 2021.

Before we delve into the lawsuit, let’s go over the process for California’s gubernatorial recall, as the effort to unseat Newsom is only the second time in the state’s history that the gambit has made it all the way to an election. The first gubernatorial recall election in California resulted in incumbent Democratic Governor Gray Davis being replaced by Republican Arnold Schwarzenegger. California voters have unsuccessfully attempted to recall many previous governors as well as other high-ranking government officials.

Under California state law, a sitting governor can be thrown out of office or “recalled” before that person’s term has expired. Leading the charge against Gavin Newsom is Orrin E. Heatlie (R), a 52-year-old retired county sheriff’s sergeant who disagreed with Newsom’s policies. Heatlie began gathering support, and in accordance with California election law, he filed a petition to get the question of recall onto a ballot.

As a result, ballots (some of which have already been mailed to voters) will include two questions. First, “Shall GAVIN NEWSOM be recalled (removed) from the office of Governor?” Second, ballots will list candidates to replace Newsom along with an option to write in a candidate of the voter’s choosing. (A current list of the 40+ individuals seeking to replace Newsom is available here.) Pursuant to state law, Newsom himself cannot be listed as a “replacement” candidate.

When votes are tallied, 50% or more of the voters must vote “yes” on the first question in order to remove Newsom from office. If the votes to recall reach that threshold, the votes on the second question will be tallied; the candidate with the most votes, regardless of the total number of votes, will become governor for the remainder of Newsom’s term (slated to expire on January 2, 2023). If there are 50% or more “no” votes to recall, Newsom will simply complete his term as governor.

Now let’s turn to the lawsuit. Plaintiffs R.J. Beaber and A.W. Clark allege the California procedure for handling recalls is unconstitutional. They assert that California law allows for the possibility that Newsom could receive more votes against his recall than any one candidate receives for their election as his replacement. (For a little math aid, consider a situation where 51% of the voters voted to recall Newsom, meaning that 49% voted to keep him. Then, votes among the replacement candidates are scattered among them such that the “winner” only receives 10% of the votes.) The complaint characterizes this process as affording two votes to folks who support Newsom, while only one to those who wish to replace him.

The complaint asserts that this mathematical disparity is a violation of the equal protection clause:

Thus, although Gov. Newsom could receive more votes against his recall on issue 1, still a candidate who seeks to replace him and who receives fewer votes could be chosen to be Governor.This process is violative of the Equal Protection and Due Process Clauses of the Constitution’s Fourteenth Amendment, because it flies in the face of the federal legal principle of “one person, one vote,” and gives to voters who vote to recall the Governor two votes — one to remove him and one to select a successor, but limits to only one vote the franchise of those who vote to retain him and that he not be recalled, so that a person who votes for recall has twice as many votes as a person who votes against recall. This is unconstitutional both on its face and as applied.

The complaint goes on by arguing that an unfettered right to vote is “the essence of a democratic society” and that restrictions on that right “strike at the heart of representative government.” Calling out California’s procedure for denying voting rights via “debasement and dilution, so that they are prohibited and prevented from the free exercise of their franchise,” the plaintiffs ask the court to halt the recall election in its current form. Plaintiffs offer two possible remedies: either stop the recall election altogether, or allow Newsom to be listed as a “replacement candidate.” That way, voters who oppose Newsom’s recall could vote to elect Newsom as his own replacement.

The lawsuit may initially seem like a longshot. However, it’s noteworthy that less than one week ago, noted constitutional law scholar Erwin Chemerinsky co-authored an op-ed in the New York Times titled There Is a Problem With California’s Recall. It’s Unconstitutional. In the article, Chemerinsky and his co-author Berkley law professor Aaron S. Edlin call the equal protection violation posed by the the California recall law “not be a close constitutional question.”

“It is true that federal courts generally are reluctant to get involved in elections,” they allow. “But the Supreme Court has been emphatic that it is the role of the judiciary to protect the democratic process and the principle of one-person one-vote.”

The authors went on to note that any constitutional defect was not relevant to the 2003 recall of Governor Gray Davis. They explain that “Davis was removed from office after receiving support from 44.6 percent of the voters” (in other words, the majority — 55.4% — wanted him gone) and that “his successor, Arnold Schwarzenegger, was elected to replace him with 48.5 percent of the vote” (the most of any replacement). Therefore, they conclude, “Mr. Schwarzenegger was properly elected” — the core point being that more people wanted Schwarzenegger (at 48.5%) than wanted Davis (at 44.6%) in a multi-person race.

Professors Chemerinksy and Edlin end their article with a statement that may have urged Beaber and Clark’s lawsuit:

The stakes for California are enormous, not only for who guides us through our current crises — from the pandemic to drought, wildfires and homelessness — but also for how we choose future governors. The Constitution simply does not permit replacing a governor with a less popular candidate.

Law&Crime reached out to Stephen Yagman and Joseph Reichmann, attorneys for the plaintiffs, who declined to comment, citing their firm’s policy: “[t]here are only legal issues for the court to decide, and nothing in this matter has anything to do with personalities or happenings of a fact-specific event.”

Attorneys for the state of California did not immediately respond to request for comment.

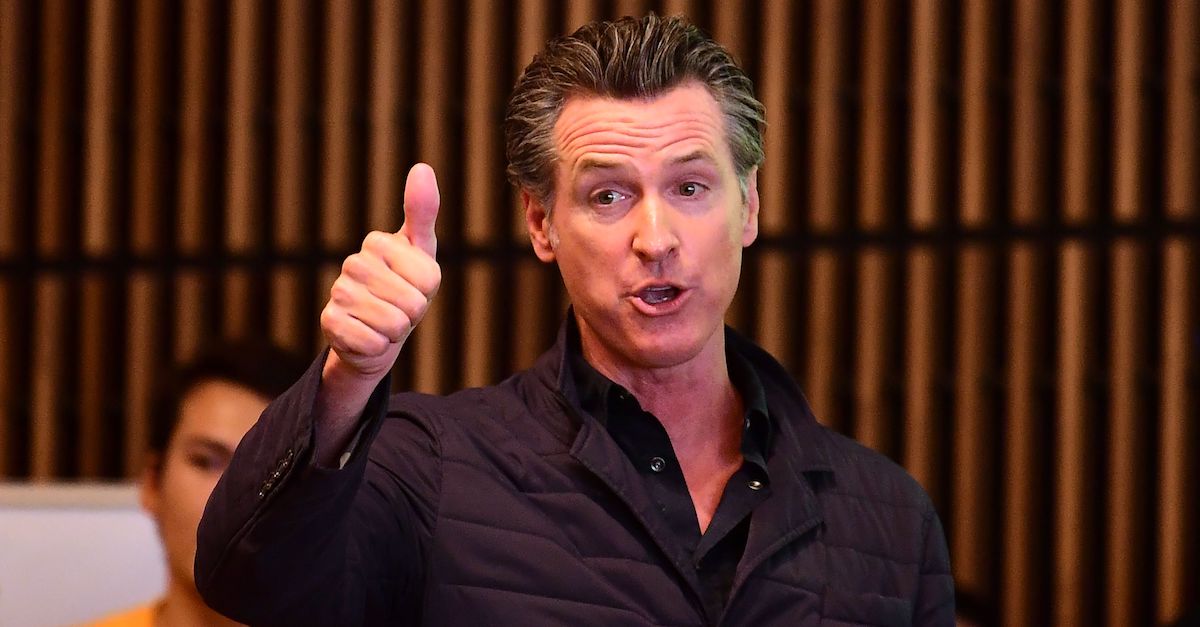

[image via Frederic J. Brown/AFP/Getty Images]