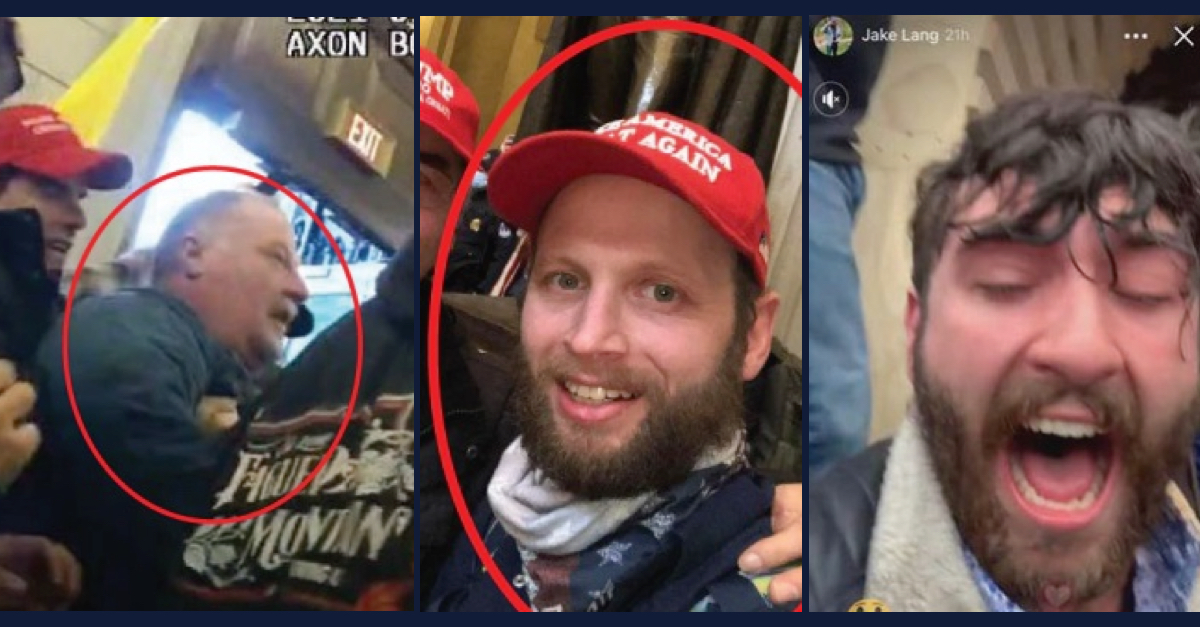

L-R: Joseph Fischer, Garret Miller, Edward Jacob Lang (via FBI court filings).

Attorneys for three men accused in the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol appeared to rankle judges in oral arguments at a high-stakes appeal that could upend hundreds of cases in the government’s pursuit of those who participated in the deadly riot.

The three-judge panel appeared skeptical of the effort to disarm prosecutors of one of their most effective tools in Jan. 6 cases — and throwing hundreds of cases into turmoil in a way that could prove a boon to former President Donald Trump.

Joseph Fischer, Garret Miller, and Edward Jacob Lang all face multiple charges in three separate cases. The most serious of those charges — obstruction of an official proceeding of Congress — carries a potential 20-year prison sentence.

Defense attorneys have argued that the statute does not apply to the actions of the defendants on Jan. 6, when scores of Trump supporters mobbed law enforcement at the Capitol and breached the building, forcing Congress to halt its certification of Joe Biden‘s 2020 electoral win.

Lawyers have repeatedly tried to get the obstruction charge dismissed, and for the most part, they have failed: eighteen federal district judges in Washington have upheld the obstruction charge in Jan. 6 cases, following in the footsteps of U.S. District Judge Dabney Friedrich, a Trump appointee who was the first to issue a written ruling on the matter.

One judge, however, agreed with the defendants.

In March, U.S. District Judge Carl Nichols, also a Trump appointee, sided with defendant Miller and dismissed that particular charge. In his ruling, Nichols found that the statute, which Congress enacted in 2002 in the wake of the Enron scandal, “requires that the defendant have taken some action with respect to a document, record, or other object in order to corruptly obstruct, impede or influence an official proceeding.”

Since Miller “is not alleged to have taken such action,” Nichols found, the charge should be dismissed.

The Justice Department appealed from that ruling.

A decision to uphold the dismissal would likely wreak havoc on the government’s years-long prosecution of the Jan. 6 attack. More than 290 defendants have been charged with felony obstruction under the statute, or attempting to do so. Some of the most recognizable names to emerge from the attack — including so-called “QAnon shaman” Jacob Chansley, Scott Fairlamb, and Paul Hodgkins — have pleaded guilty to the offense, while federal juries have convicted high-profile defendants such as Guy Reffitt and Oath Keepers leader Stewart Rhodes, along with four of his co-defendants, on the count.

A federal judge has also found that Trump himself “more likely than not” committed felony obstruction of justice in connection with the Capitol riot, and the House committee investigating Jan. 6 has indicated that it will issue criminal referrals with its final report, which is expected next week.

A Key Legal Issue: What Does “Otherwise” Mean in the Obstruction Statute?

The statute at issue, 18 U.S.C. § 1512, reads (in relevant part) as follows:

(c) Whoever corruptly —(1) alters, destroys, mutilates, or conceals a record, document, or other object, or attempts to do so, with the intent to impair the object’s integrity or availability for use in an official proceeding; or(2) otherwise obstructs, influences, or impedes any official proceeding, or attempts to do so,shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than 20 years, or both.

Prosecutors have argued that while the enumerated offenses in the first subsection are specifically aimed at actions like destroying evidence, the second subsection, starting with the word “otherwise,” is meant to essentially be a “catchall” to address any other action, “corruptly” taken, to block “any official proceeding.”

Defendants have argued that the statute is confined to actions such as destroying potentially incriminating documents, as consulting firm Arthur Anderson was found to have done on behalf of Enron as the then-crumbling energy company was starting to crumble, leading to what was then the largest corporate bankruptcy in the world.

During Monday’s appellate hearing before a three-judge panel of the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, Assistant U.S. Attorney James Pearce urged the judges to uphold the findings of at least 18 district court judges.

“The word ‘otherwise’ indicates that the provision encompasses conduct other than [document or evidence tampering],” Pearce argued. He was almost immediately cut off by Circuit Judge Gregory G. Katsas.

“Why doesn’t it indicate offenses similar to [those] in [subsection] c(1)?” asked Katsas, a Trump appointee.

Pearse said that the most “natural meaning” of the word otherwise is to mean “in a different way,” not “in a different but similar way.”

Katsas pointed to a 2008 Supreme Court case, Begay v. United States, which found that the use of the word “otherwise” in the statute relevant to that case was indeed limiting, and not intended as a catchall. Pearse said that the different construction of the respective statutes in the Begay case and this one called for a different reading of the statutes.

Pearse argued that to give “otherwise” a “more limited reading” would lead to “going down a path with no one really knowing what this means.”

“If you stick with the plain text of the prohibition, you don’t take that path,” Pearse added.

The other two judges on the panel, Trump appointee Justin R. Walker and Biden appointee Florence Y. Pan, tried to get Pearse to define the word “corruptly” for purposes of the statute — even though, as Pan noted, that particular issue might not be before the court.

Pearse said that the definition of “corruptly” must include an “intent to obstruct,” but is not limited to that, adding that it “also includes acting either with independently corrupt or unlawful means, or corrupt purpose.”

Pearse also said that, in the prosecution’s reading of the statute, the word “corruptly” did not necessarily need to include a desired financial outcome on the part of the defendant.

Toward the end of his argument, Pearse returned to the position of “otherwise” in the statute.

“The way 1512 is structured, (c)(2) sits at the end of most serious provisions,” Pearse said. “That’s exactly where a reader would expect a catchall provision to set.”

Pearse also argued that the word “otherwise” serves as a way to contrast the types of offenses that could function as obstruction because it “shifts focus from evidence spoliation to efforts to thwart the proceeding itself.

“Was This a Protest, or Was This Something More?”

While Judge Katsas’ questioning of Pearse appeared to indicate an inclination for siding with the defendants, Judges Walker and Pan were clearly rankled by some of Smith’s arguments and analogies.

Defense attorney Nicholas Smith began by saying that the statute has consistently been used to charge crimes of “evidence impairment.” Judge Pan asked the lawyer for “textual proof” of that position, and Smith noted that cases cited by prosecutors were specifically those involving evidence impairment.

“None of those cases say it’s an evidence impairment crime,” Pan said. “They happen to have facts that involved evidence impairment.”

Smith replied that it’s been “assumed” because prior to Jan. 6, no one had used the obstruction statute in this way.

“Is your only evidence that it’s been assumed is that it hasn’t come up?” Pan asked. Smith said that the statute has never been used in the context of political protests at the Capitol, but rather in cases of congressional inquiries or investigations. Pan said that the situations aren’t comparable, and after several exchanges in which the lawyer repeatedly talked over the judge, Pan reminded Smith of exactly how things work before appellate judges.

“When I start speaking, you need to stop,” Judge Pan told Smith.

“Thank you,” replied Smith.

Moments later, however, Pan again expressed her frustration with Smith, as the two engaged in a back-and-forth over whether the defense needed the judges to find that the statute is ambiguous in order to analyze its meaning. Smith argued that they did not, but that each word needed to be scrutinized and read “in context,” and even appeared to imply that certification process was not necessarily an “official proceeding” for purposes of the statute — despite the fact that all the district judges, including Nichols, have agreed that it was.

“I find it a little frustrating, because I feel like it’s Whac-A-Mole,” Pan said, referring to the classic arcade game in which a player must use a mallet to strike the heads of “moles” that continually pop up from different holes. “I try to hone in on one aspect [of the argument] and you talk about another.”

“No more moles, Your Honor,” Smith promised.

Smith also ran into trouble with Judge Walker when he appeared to argue that the obstruction charge in the context of Jan. 6 cases was being misused.

“The government is not without remedies for every hypothetical we could come up with,” Smith told the judges, adding that there are already specific charges for offenses like assaulting police, interfering with law enforcement, and trespass — all of which have been applied to Jan. 6 defendants. “The crime [the government has] created is sitting parasitically on every other crime they’ve alleged. It’s not adding unique content to a crime, it is merely turbo-charging the sentencing guidelines of that offense.”

“The ramifications extend well beyond Jan. 6,” Smith added, attempting again to compare those who rushed the Capitol on Jan. 6 to political protesters, but Judge Walker cut him off.

“You’ve made this point three times,” Walker said. “One of your clients said ‘This was war,’ period. ‘This was no protest,’ period. So we’re not talking about a protest, right?”

“We would push back on–” Smith began.

“Was this a protest, or was this something more?” Walker said, cutting Smith off.

“Absolutely not,” Smith replied.

“Absolutely not what?” Walker asked.

Smith clarified that people running into the Capitol to stop police officers, for example, was not a “protest.”

“None of that happened in the Florida recount,” Walker said.

The judge wasn’t finished.

“I do take some umbrage,” Walker began, saying that Smith may have a “strong textual argument” and that some parts of the case might be a close call. “But you seem to have made a theme today of saying it would an injustice, a gross imbalance of the equities to treat your clients the way courts and prosecutors treat lawful protestors, for whom no prosecution should be brought, and even unlawful but peaceful protestors.”

“The teams of lawyers that went down to Florida, that you analogize to Jan. 6 rioters today, they didn’t say ‘civil war should start.’ They didn’t use a grappling hook and rope and level three vest. They didn’t say a Democratic Congress should hang in the gallows, like one of your clients did … I could go on and on,” Walker continued. “I think you would have to concede that this has nothing to do with a protestor outside the Capitol with a sign, or [one who] goes down to Florida to ensure a fair election, right?”

Smith told the judge that he made an “excellent point,” and tried to “clarify” that he was specifically talking about the fact that “hundreds of people” went inside the Capitol, with the “same intent” — stopping Congress from certifying the results of the 2020 election — but some are being charged with an obstruction felony while others are being charged with trespassing misdemeanors.

“Isn’t what you’re referring to exercise of prosecutorial discretion?” Judge Pan interjected. Smith continued to try to make his argument, saying that using the obstruction charge in this way is “unprecedented.”

“You don’t think this was unprecedented?” Walker asked. Smith said that it “absolutely” was.

“Then it’s not surprising that there’s no precedent for prosecution,” Walker replied. Smith — again — said that the actions were the same.

Pan again asked Smith to explain why the charging decision wasn’t just prosecutorial discretion, saying that it’s “commonplace” for prosecutors to “look at the conduct of each individual and exercise their discretion to determine what to charge.”

Smith wrapped up his argument without conceding that particular point.

The judges reserved decision on a ruling.