As anyone with a “Schoolhouse Rock“-level understanding of U.S. civics understands, the duty of the legislative branch of government—and the members of Congress who comprise it—is to pass laws.

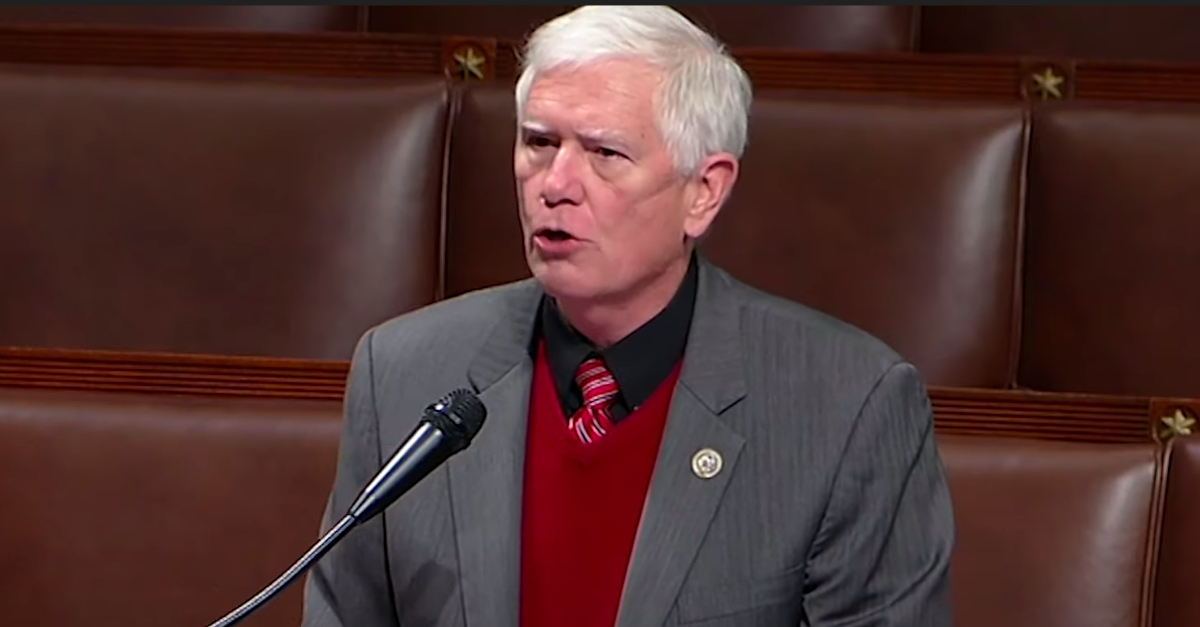

On Tuesday night, the Department of Justice emphasized that those responsibilities do not include instigating an attack on the U.S. Capitol. The seemingly intuitive clarification came as bad news to Rep. Mo Brooks (R-Ala.), a Donald Trump-loyalist congressman trying to fend off a lawsuit by Rep. Eric Swalwell (D-Calif.) accusing him of doing just that on Jan. 6th.

“The complaint alleges that Brooks conspired with others to instigate a violent attack on the U.S. Capitol and incited a riot there,” the Justice Department’s trial attorney Taheerah K. El-Amin noted in a 22-page brief on Tuesday evening.

“Instigating such an attack plainly could not be within the scope of federal employment,” it continues.

“Kicking Ass”

Swalwell claims that Brooks shares responsibility for inciting the invasion of the U.S. Capitol by amplifying Trump’s lie of election fraud and delivering an inflammatory speech in front of the Ellipse, quoted extensively in the lawsuit.

“Today is the day American patriots start taking down names and kicking ass,” Brooks proclaimed on Jan. 6th. “Now, our ancestors sacrificed their blood, their sweat, their tears, their fortunes, and sometimes their lives, to give us, their descendants, an America that is the greatest nation in world history. So I have a question for you: Are you willing to do the same? My answer is yes. Louder! Are you willing to do what it takes to fight for America? Louder! Will you fight for America?”

Brooks denies inciting any attack on the U.S. Capitol, but the Justice Department notes that the alleged conduct if proven would not fall under his duties as a congressman.

The Federal Employees Liability Reform and Tort Compensation Act of 1988, better known as the Westfall Act, immunizes federal employees from civil damages for actions taken over the course of their official duties. The law—previously arcane to non-government workers—has found increasing prominence as Attorney General Merrick Garland’s Justice Department has grappled with whether or when to defend Trump and his allies in civil litigation.

Garland’s Justice Department chose to defend Trump against allegations by columnist E. Jean Carroll that the former president defamed her by denying that he raped her.

In that case, the DOJ decided that Trump’s comments to reporters that Carroll was a “liar,” “slut,” or “not my type” happened during the course of one of his official duties: speaking with the press. Though arguing for Trump’s immunity, the department offered no excuses for the 45th president’s “crude and disrespectful” comments.

The DOJ also argued that former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo acted under the scope of his official duties when allegedly breaching the agency’s obligations to underwrite the legal fees of Gordon Sondland, a former Ambassador to the European Union turned key witness against Trump during the former president’s first impeachment.

“Electioneering or Campaign Activities”

For Rep. Brooks, however, the Trump-era definition of official duties was a bridge too far.

“Instigating an attack on the United States Capitol would not be within the scope of a Member of Congress’s employment,” a subheading of the DOJ’s brief states, bluntly.

The Alabama Republican insists that he was talking about the 2022 and 2024 elections when he told the crowd of Trump supporters to start “kicking ass” on Jan. 6th.

For the Justice Department, this defense makes Brooks no more eligible for Westfall Act immunity because he would be engaged in “electioneering or campaign activities,” which also do not fall under his duties as a federal employee.

“The record indicates that Brooks’s appearance at the January 6 rally was campaign activity, and it is no part of the business of the United States to pick sides among candidates in federal elections,” the DOJ’s brief states. “Members of Congress are subject to a host of restrictions that carefully distinguish between their official functions, on the one hand, and campaign functions, on the other.”

The rally where Brooks spoke was organized by Trump-supporting groups like tea party operative Amy Kremer’s Women For America First.

“To be sure, the rally on January 6 differed from a typical campaign rally because it occurred two months after Election Day,” the Justice Department wrote. “But participating at a post-election rally that is paid for by a political campaign or its supporters, and that is concededly directed toward affecting the electoral outcome of a presidential election on behalf of a specific candidate or garnering support for the next election, is no less an electioneering or campaign activity.”

As noted by legal scholar Steve Vladeck, the Justice Department decision does not fully end the Alabama Republican’s quest for immunity. Brooks can petition the court to make that determination.

A communication director for Brooks did not immediately respond to an email requesting comment.

(Image via YouTube screengrab)