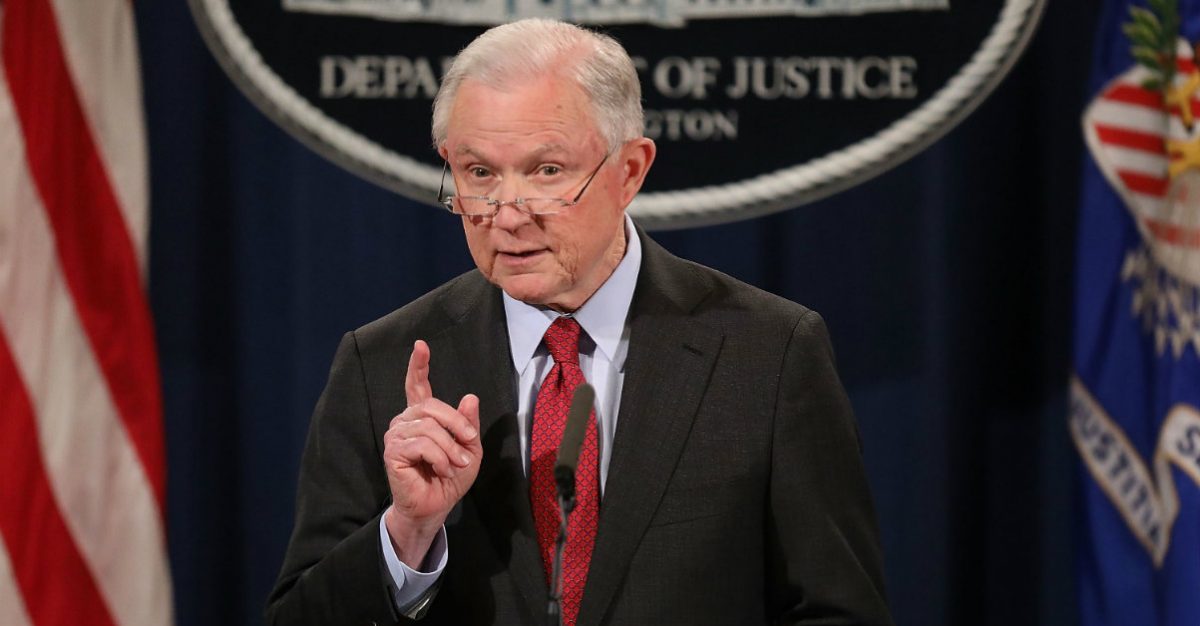

On July 3, U.S. Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced that the DOJ was “rescinding 24 guidance documents that were unnecessary, outdated, inconsistent with existing law, or otherwise improper.”

Curiously enough, each point of guidance, document or tool rescinded by Sessions — in line with recommendations from Regulatory Reform Task Forces established by President Donald Trump — was initially drafted to offer basic legal and political understanding to various and distinct minority groups, broadly defined, throughout the United States.

Most of the rescissions involve so-called “guidance” documents which merely make the law accessible. Cutting up the guidance documents below does not — for now — repeal the underlying law. However, without these plain-English guidance documents and interpretations, it’ll make it harder for non-lawyers to understand what the law says (or how it protects them). These rescissions could result in less protection for minority groups. Some of the rescissions involve documents which have since been replaced by newer versions, e.g., for a new grant year.

Here’s a tidy summary for understanding what’s on Sessions’ mind as the nation prepares to celebrate her independence from the King of England.

Revocations 1-7 deal with the way children are treated when they are suspected or accused of breaking the law. The federal Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act, signed by President Ford, contains four “core” requirements. These guidance letters affect interpretations of the law.

One of the law’s core requirements is “removal.” It generally requires juveniles to not be housed with adult inmates (with limited exceptions). Another is “separation.” When juveniles are housed with adults under one of those limited exceptions, they must be separated from the sights and sounds of adult incarceration. Another is “deinstitutionalization.” It seeks to provide alternatives to jail for youths who commit acts which, due to their age, are crimes. Adults would not be arrested for such acts. Examples are drinking, truancy, running away, and smoking.

Revocation 8 involves a federal program which pays back state and local governments for incarcerating undocumented criminal aliens who have committed more serious crimes.

Revocation 9 deals with research into whether schools disproportionately dole out punishments on the basis of race, national origin, native language, sex, or disability. It also deals with research into the role of school resource officers.

Revocations 10-11 deal with advice for home buyers and home owners. Revocation 10 involves people seeking a mortgage. Revocation 11 involves warnings against so-called “predatory” home equity loans. It warns people, especially those with poor credit and the elderly, to carefully review the terms of home improvement loans.

Revocation 12 takes aim at a George W. Bush era document prepared to alert all Americans about the unconstitutional nature of being discriminated against on the basis of their national origin. To be clear: this protection technically has nothing to do with immigration status whatsoever–in America, it’s illegal to discriminate against any American over issues arising from their national origin (or a family member’s national origin). But that’s a bitter pill for Sessions, et, al.

Revocations 13-14 deal with workers’ rights for various classes of immigrants to the United States. Revocation 13 targets a document prepared to assist immigrants who encounter employment discrimination. Revocation 14 targets a guidance document whose name should alone should suffice to mention, “Refugees and Asylees Have the Right to Work.” It’s easy enough to see why Sessions and his apparatchiks have a problem here.

Revocations 15-17 target people who don’t understand English particularly well, but who may nevertheless occasionally find themselves in need of accessing the U.S. court system. As an explanatory point, in 2012, the Obama administration developed a tool “in response to requests for technical assistance from courts and others involved in planning and implementing measures to improve language assistance services in courts for limited English proficient (LEP) individuals.”

Revocations 18-24 are aimed at various recipients of affirmative action policies. The final revocation in this grouping makes Sessions’ decision here easy enough to understand. Revocation 24 expresses official disapproval of a Q&A sheet prepared to explain Supreme Court precedent on affirmative action. That sheet noted, “[This document] reiterates the continued support of the Departments of Education and Justice for the voluntary use of race and ethnicity to achieve diversity in education.”

[image via Getty]

Follow Colin Kalmbacher on Twitter: @colinkalmbacher

Follow Aaron Keller on Twitter: @AKellerLawCrime

[Image via Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images.]