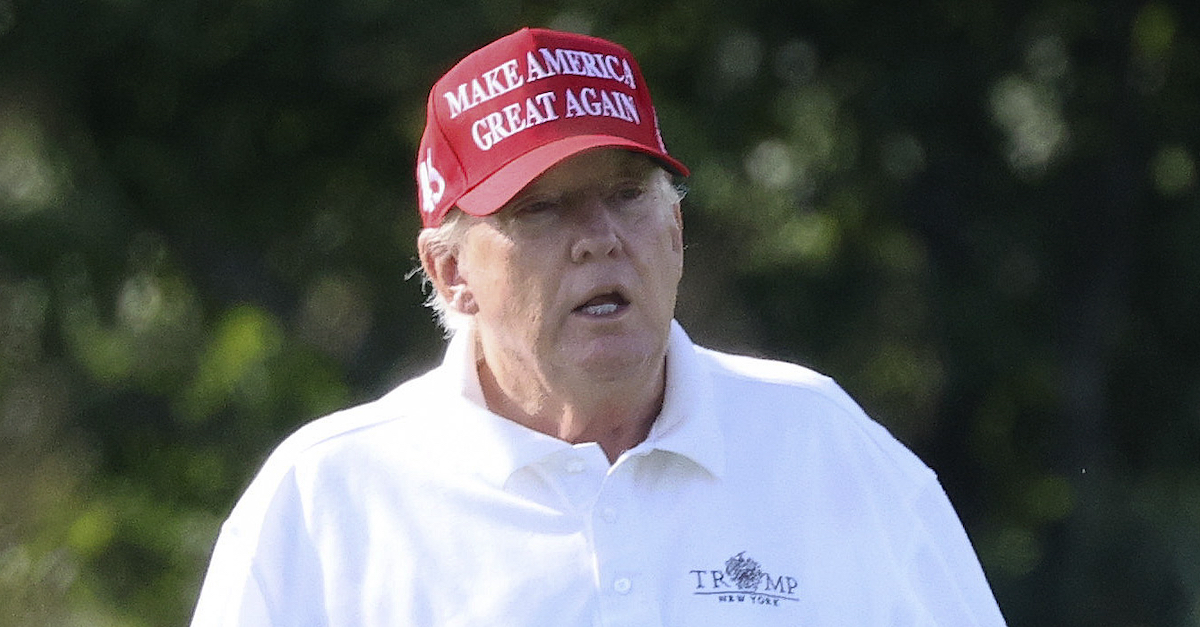

Former U.S. President Donald Trump golfs at Trump National Golf Club September 13, 2022 in Sterling, Virginia. (Photo by Win McNamee/Getty Images.)

Federal prosecutors on Friday evening asked the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals to issue a “partial” and “modest” stay of a district judge’s order that blocked a criminal review of materials seized from Donald Trump’s Mar-a-Lago residence and resort club.

Trump’s attorneys asked for an independent special master to conduct a privilege review — a process that would potentially separate any private material from items federal prosecutors said were classified government documents. U.S. District Judge Aileen M. Cannon, a Trump appointee, agreed with Trump’s request. Cannon said the special master review was necessary, in part, because she wanted a third party to confirm whether the seized material truly was classified as prosecutors suggested. The move by Cannon flummoxed many observers, including at least one seasoned national security lawyer who is not involved with the case but who is closely watching it, since most judges defer to government assertions about classified materials and national security matters.

Prosecutors are now asking an appellate court to stay Cannon’s ruling and, in essence, to allow the government to examine the fruits of the warrant as part of a criminal investigation.

“The district court has entered an unprecedented order enjoining the Executive Branch’s use of its own highly classified records in a criminal investigation with direct implications for national security,” the U.S. Department of Justice wrote in Friday evening’s filing.

“In August 2022, the government obtained a warrant to search the residence of Plaintiff, former President Donald J. Trump, based on a judicial finding of probable cause to believe that the search would reveal evidence of crimes including unlawful retention of national defense information,” prosecutors continued. “Along with other evidence, the search recovered roughly 100 records bearing classification markings, including markings reflecting the highest levels of classification and extremely restricted distribution.”

Trump convinced Cannon, who was not the original magistrate judge who signed off on the warrant, to enjoin prosecutors from reviewing the seized materials for “criminal investigative purposes.” Canon did allow a separate review of the material for “intelligence classification and national security assessments” with personnel distinct from those who would be involved in a parallel criminal probe.

Bemoaning that a review by a special master “will last months,” the DOJ said Judge Cannon provided a form of “extraordinary relief” for Trump. The DOJ also feared that it would be difficult to unwind the national security review process from the criminal probe, since the two issues are tightly woven.

From the motion, at length:

Although the government believes the district court fundamentally erred in appointing a special master and granting injunctive relief, the government seeks to stay only the portions of the order causing the most serious and immediate harm to the government and the public by (1) restricting the government’s review and use of records bearing classification markings and (2) requiring the government to disclose those records for a special-master review process. This Court should grant that modest but critically important relief for three reasons.

First, the government is likely to succeed on the merits. The district court appointed a special master to consider claims for return of property under Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 41(g) and assertions of attorney-client or executive privilege. All of those rationales are categorically inapplicable to the records bearing classification markings. Plaintiff has no claim for the return of those records, which belong to the government and were seized in a court-authorized search. The records are not subject to any possible claim of personal attorney-client privilege. And neither Plaintiff nor the court has cited any authority suggesting that a former President could successfully invoke executive privilege to prevent the Executive Branch from reviewing its own records. Any possible assertion of executive privilege over these records would be especially untenable and would be overcome by the government’s “demonstrated, specific need” for them, United States v. Nixon, 418 U.S. 683, 713 (1974), because they are central to its ongoing investigation.

The second reason cited by the DOJ was that “government and the public would suffer irreparable harm absent a stay.”

Again, from the motion (legal citations omitted):

[A]s the head of the Counterintelligence Division of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) explained in a sworn declaration, the criminal investigation is itself essential to the government’s effort to identify and mitigate potential national-security risks. The court’s order hamstrings that investigation and places the FBI and Department of Justice (DOJ) under a Damoclean threat of contempt should the court later disagree with how investigators disaggregated their previously integrated criminal-investigative and national-security activities. It also irreparably harms the government by enjoining critical steps of an ongoing criminal investigation and needlessly compelling disclosure of highly sensitive records, including to Plaintiff’s counsel.

Former U.S. President Donald Trump’s Mar-a-Lago estate is seen on September 14, 2022 in Palm Beach, Florida. (Photo by Joe Raedle/Getty Images.)

The third reason to partially stay Cannon’s order, according to the DOJ, was that a partial stay would “impose no cognizable harm” on Trump:

It would not disturb the special master’s review of other materials, including records potentially subject to attorney-client privilege. Nor would a stay infringe any interest in confidentiality: The government’s criminal investigators have already reviewed the records bearing classification markings, and the district court’s order contemplates that the IC may continue to review and use them for certain national- security purposes.

A lengthy factual recitation of the matter was then included in Friday’s filing for the benefit of the appellate court: the National Archives and Records Administration sought “what appeared to be missing records subject to the Presidential Records Act (PRA),” and Trump handed over “15 boxes of records in January 2022,” according to the filing.

“NARA referred the matter to DOJ, noting that highly classified records appeared to have been improperly transported and stored,” the filing adds.

At first, the document indicates, Trump didn’t assert any claims of privilege over the material. Nor did Trump attempt to assert that the material had been declassified, the DOJ wrote.

Some 38 additional documents were handed over to the DOJ from Trump’s attorneys after a May 11 grand jury subpoena was issued, the filing states.

Trump’s attorneys asserted that no further documents were present at Mar-a-Lago and that “all responsive documents” had by that point been turned over to the government, the filing goes on.

The investigation, however, didn’t end there.

“The FBI uncovered evidence that the response to the grand-jury subpoena was incomplete, that classified documents likely remained at Mar-a-Lago, and that efforts had likely been undertaken to obstruct the investigation,” the filing explains.

That evidence led to the August search and seizure of additional contested material.

Federal prosecutors say FBI agents seized these materials from Mar-a-Lago. The contents of the documents were redacted with white squares. (Image via an Aug. 31, 2022 federal court filing.)

“The government executed the warrant on August 8, 2022. The search recovered roughly 11,000 documents from the storage room as well as Plaintiff’s private office, roughly 100 of which bore classification markings, including markings indicating the highest levels of classification,” the DOJ wrote. “In some instances, even FBI counterintelligence personnel required additional clearances to review the seized documents.”

Subsequent paragraphs in Friday’s motion attempted to rubbish Cannon’s logic for ordering a special master review (again, legal citations to the record are omitted herein):

The court did not resolve the government’s arguments that a former President cannot assert executive privilege to prevent the Executive Branch from reviewing its own records and that any assertion of privilege here would in any event be overcome. Instead, the court stated only that “even if any assertion of executive privilege by Plaintiff ultimately fails,” he should be allowed “to raise the privilege as an initial matter.”[ . . . ]The district court erred in exercising jurisdiction as to the records bearing classification markings. Even if the exercise of jurisdiction were proper, there would be no basis for preventing the government from using its own records. And the court’s suggestion that there are “factual and legal disputes” about the records bearing classification markings is incorrect and not relevant in any event.

“The district court’s order should be stayed to the extent it (1) enjoins the further review and use for criminal-investigative purposes of the seized records bearing classification markings and (2) requires the government to disclose those records for a special-master review process,” prosecutors asked the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals to agree.

The 11th Circuit’s electronic document filing system was down for some time on Saturday, but it appears that no ruling on the request has been issued as of the time of this report.

The entire DOJ motion is below: