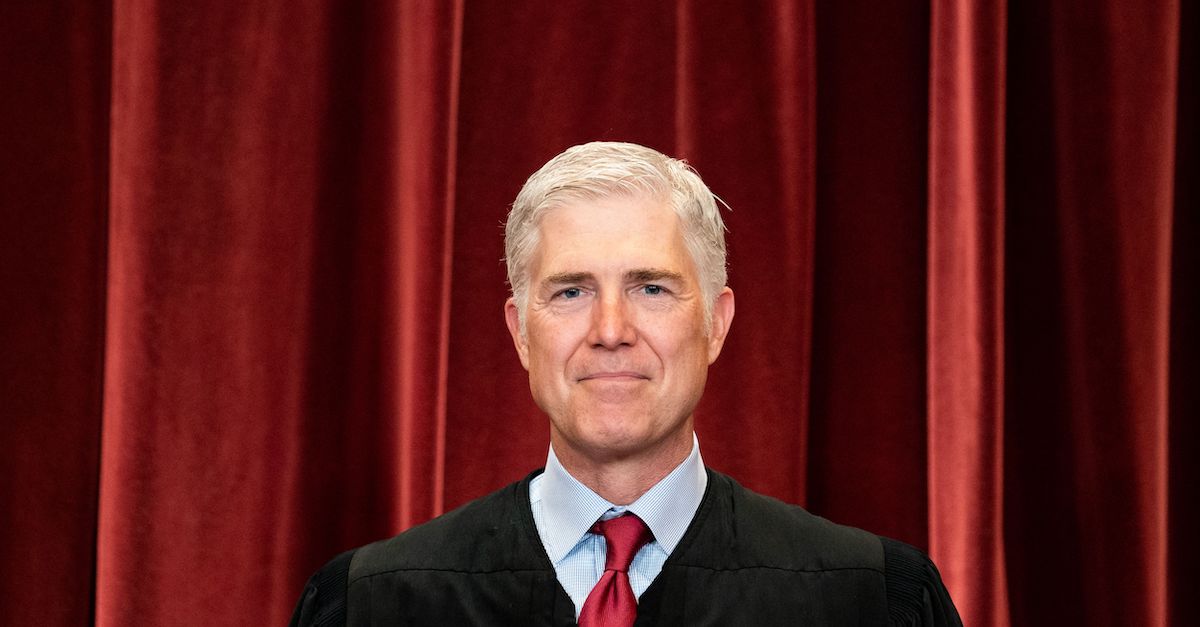

Associate Justice Neil Gorsuch stands during a group photo of the Justices at the Supreme Court in Washington, DC on April 23, 2021.

The Supreme Court of the United States on Thursday confronted and dismissed a novel claim in a case out of Texas where an elected official claimed his formal censure by colleagues was a violation of the First Amendment.

In ruling against the upset official, the nine justices offered a contemporary expression of the longstanding principle that the best way to counter offensive free speech is simply more free speech.

Stylized as Houston Community College System v. David Buren Wilson, the dispute here arises from the “stormy” tenure of the respondent, David Wilson, who is and has been a member of the HCC Board of Trustees since he was first elected to the position in 2013.

Justice Neil Gorsuch, writing for a unanimous court, notes that since taking office, Wilson tied up the board in lawsuit after lawsuit which forced the HCC to spend well in excess of $270,000 defending against the litigation. And the adversarial behavior didn’t stop there.

“Wilson charged the Board in various media outlets with violating its bylaws and ethical rules,” the opinion explains. “He arranged robocalls to the constituents of certain trustees to publicize his views. He hired a private investigator to surveil another trustee, apparently seeking to prove she did not reside in the district that had elected her.”

In 2018, it all came to a head.

The board, having had enough, adopted a public resolution “censuring” Wilson and saying that his years of oppositional conduct were “not consistent with the best interests of the College” and “not only inappropriate, but reprehensible.”

In addition to the censure, the board “imposed certain penalties,” Gorsuch notes. Those included making Wilson ineligible for a board officer position in the year of his censure, nixing college-related travel reimbursements, and limiting his access to other board funds.

With one of his numerous lawsuits still extant, Wilson amended the complaint to include First Amendment claims against the board members and the university system for the censure and resulting penalties imposed. Over time, throughout the years of ensuing litigation, Wilson removed the individual board members from his lawsuit and left the HCC as the lone defendant.

A district court ruled against him. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit overturned that decision in part, finding that his censure was a violation of the First Amendment but sustaining his loss on the penalty claim because those perks of elected leadership do not qualify as a constitutionally-recognized “entitlement.”

The university system filed for review with the nation’s high court on the remaining constitutional claim and at least five justices agreed to take up the case. During the merits phase, Wilson also argued against the Fifth Circuit’s denial of his claim over the loss of board perks. But, fatally for that claim, he failed to file a cross-petition for review. So, Gorsuch says, the Supreme Court could only consider whether a censure rises to the level of a First Amendment violation.

The relatively brief opinion begins its analysis with a lengthy historical rundown of how censure by elected bodies is a “longstanding practice” that dates back to “colonial times” in the country.

“The parties supply little reason to think the First Amendment was designed or commonly understood to upend this practice,” Gorsuch notes, casting a wide net that includes stories about President Thomas Jefferson and Senator Joseph McCarthy up to present day.

“[E]lected bodies in this country have long exercised the power to censure their members,” the opinion explains. “In fact, no one before us has cited any evidence suggesting that a purely verbal censure analogous to Mr. Wilson’s has ever been widely considered offensive to the First Amendment.”

The point about history is underscored as the opinion eventually makes a hard pivot to constitutional principles of free expression:

On Mr. Wilson’s telling and under the Fifth Circuit’s holding, a purely verbal censure by an elected assembly of one of its own members may offend the First Amendment. Yet we have before us no evidence suggesting prior generations thought an elected representative’s speech might be “abridg[ed]” by that kind of countervailing speech from his colleagues. Instead, when it comes to disagreements of this sort, history suggests a different understanding of the First Amendment—one permitting “[f]ree speech on both sides and for every faction on any side.”

Gorsuch goes on to say that a “retaliatory action” First Amendment claim has to result in negative consequences–and outlines a broad suite of such consequences before shutting Wilson down.

“Some adverse actions may be easy to identify—an arrest, a prosecution, or a dismissal from governmental employment,” the opinion notes. “‘[D]eprivations less harsh than dismissal’ can sometimes qualify too. At the same time, no one would think that a mere frown from a supervisor constitutes a sufficiently adverse action to give rise to an actionable First Amendment claim.”

Wilson, the opinion explains, is an elected official and, in the United States, politicians are a class of people who are expected to “shoulder a degree of criticism about their public service from their constituents and their peers—and to continue exercising their free speech rights when the criticism comes.”

“[T]he only adverse action at issue before us is itself a form of speech from Mr. Wilson’s colleagues that concerns the conduct of public office,” Gorsuch continues. “The First Amendment surely promises an elected representative like Mr. Wilson the right to speak freely on questions of government policy. But just as surely, it cannot be used as a weapon to silence other representatives seeking to do the same.”

The opinion later distinguishes certain forms of censures from the one at issue in the present case–noting that censures of students, employees or licensees by the government would likely be on much less firm territory and could potentially give rise to a successful First Amendment retaliation claim.

Here, on the other hand, Gorsuch notes, Wilson was on equal footing with those who censured him and he responded to the alleged retaliation by continuing to criticize his peers for what they did to him.

Again the opinion at length:

The censure at issue before us was a form of speech by elected representatives. It concerned the public conduct of another elected representative. Everyone involved was an equal member of the same deliberative body. As it comes to us, too, the censure did not prevent Mr. Wilson from doing his job, it did not deny him any privilege of office, and Mr. Wilson does not allege it was defamatory. At least in these circumstances, we do not see how the Board’s censure could have materially deterred an elected official like Mr. Wilson from exercising his own right to speak.

[image via ERIN SCHAFF/POOL/AFP via Getty Images]