The U.S. Supreme Court on Monday unanimously ruled that the City of Boston violated the Constitution by refusing to fly a flag belonging to a Christian organization as part of a rotating display at City Hall.

The brief opinion by outgoing Justice Stephen Breyer found that Boston did not consider the flag raising program to be a form of government speech and, “in turn,” refused to fly the flag belonging to Camp Constitution “based on its religious viewpoint.” That denial, the full court agreed, was an abridgment of the First Amendment.

Breyer’s reasoning, however, was not fully endorsed by some of the court’s more conservative members.

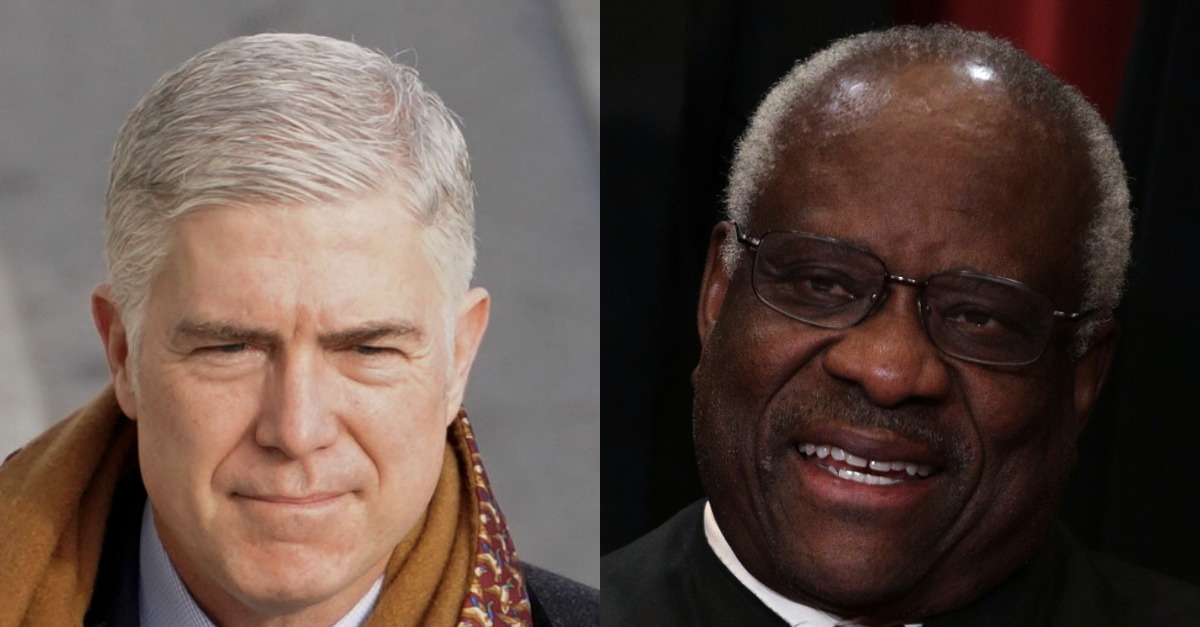

In a particularly angry concurrence, Justice Neil Gorsuch, joined by Justice Clarence Thomas, criticized Boston officials for their apparent use of a long-controversial and largely-disavowed, though not formally overruled, high court precedent known as the Lemon test. The case itself, Lemon v. Kurtzman, concerned state laws that funneled public money to religious schools. The resulting three-part test provided a victory for the secular challenger. The Supreme Court has since ruled that public funds can, in certain circumstances, be sent to religious institutions–without technically overturning Lemon itself.

“The real problem in this case doesn’t stem from Boston’s mistake about the scope of the government speech doctrine or its error in applying our public forum precedents,” the concurrence begins. “The trouble here runs deeper than that.”

To hear Gorsuch and Thomas tell it, the disfavored precedent was used to justify the city’s denial of raising the flag at issue here.

The concurrence lays out the basic framework:

Lemon held out the promise that any Establishment Clause dispute could be resolved by following a neat checklist focused on three questions: (1) Did the government have a secular purpose in its challenged action? (2) Does the effect of that action advance or inhibit religion? (3) Will the government action “excessive[ly] . . . entangl[e]” church and state?

Gorsuch accurately notes that Lemon has mostly been “abandoned” by the court due to the “chaos” that followed its original use in 1971, including numerous similar cases with decidedly at-odds results.

“After Lemon, cases challenging public displays under the Establishment Clause came fast and furious,” the concurrence states. “And just like the test itself, the results proved a garble. May a State or local government display a Christmas nativity scene? Some courts said yes, others no. How about a menorah? Again, the answers ran both ways. What about a city seal that features a cross? Good luck.”

In Boston, Gorsuch notes, the flag from the case stylized as Shurtleff v. City of Boston features a red Latin cross. Officials declined the flag on the basis that “it was the Christian flag or [was] called the Christian flag,” as the then-commissioner in charge of such displays wrote on a rejection notice. The commissioner worried that flying a religious flag at City Hall was a potential violation of the Establishment Clause.

But, the concurrence explains, Boston had previously allowed starkly similar flags in the past.

“The flags of many nations bear religious symbols,” Gorsuch notes. “So do the flags of various private groups. Historically, Boston has allowed them all. The city has even flown a flag with a cross nearly identical in size to the one on petitioners’ flag. It was a banner presented by a secular group to commemorate the Battle of Bunker Hill.”

The concurrence helpfully supplies two comparison images:

Gorsuch cites various instances in which the nation’s high court has sought to diminish the utility of the Lemon test over the years and notes that the justices have not applied it “for nearly two decades.”

In one section, the textualist justice consults history to suggest that the nation’s founders had a much more limited understanding of what “establishment” means in the context of church and state:

Beyond a formal declaration that a religious denomination was in fact the established church, it seems that founding-era religious establishments often bore certain other telling traits. First, the government exerted control over the doctrine and personnel of the established church. Second, the government mandated attendance in the established church and punished people for failing to participate. Third, the government punished dissenting churches and individuals for their religious exercise. Fourth, the government restricted political participation by dissenters. Fifth, the government provided financial support for the established church, often in a way that preferred the established denomination over other churches. And sixth, the government used the established church to carry out certain civil functions, often by giving the established church a monopoly over a specific function.

Gorsuch then wonders why, with “messages directing and redirecting the inquiry to original meaning as illuminated by history,” some local governments still apply the Lemon test. He answers his question by suggesting that certain municipalities “simply prefer the policy outcomes Lemon can be manipulated to produce.”

“Just dial down your hypothetical observer’s concern with facts and history, dial up his inclination to offense, and the test is guaranteed to spit out results more hostile to religion than anything a careful inquiry into the original understanding of the Constitution could sustain,” the concurrence argues. “Lemon may promote an unserious, results-oriented approach to constitutional interpretation. But for some, that may be more a virtue than a vice.”

Here, Gorsuch says, Boston candidly admitted their desire “to celebrate only ‘a particular kind of diversity,'” citing a city official.

“[I]f your policy goal is to lump in religious speech with fighting words and obscenity, if it is to celebrate only a ‘particular’ type of diversity consistent with popular ideology, the First Amendment is not exactly your friend,” the concurrence bitterly muses. “Dragging Lemon from its grave may be your only chance.”

The concurrence goes on to allow that, maybe, Lemon offers a “simpler and tempting alternative to busy local officials and lower courts.” But, Gorsuch says, there are other and better precedents that can be followed without having to conduct “a careful examination of the Constitution’s original meaning.”

The conclusion, however, leans back into the angry rhetoric and counsels that Lemon be left in the constitutional dustbin.

The concurrence once more, at length:

To justify a policy that discriminated against religion, Boston sought to drag Lemon once more from its grave. It was a strategy as risky as it was unsound. Lemon ignored the original meaning of the Establishment Clause, it disregarded mountains of precedent, and it substituted a serious constitutional inquiry with a guessing game. This Court long ago interred Lemon, and it is past time for local officials and lower courts to let it lie.

[images: featured Melina Mara – Pool/Getty Images and Alex Wong/Getty Images; inline via U.S. Supreme Court]