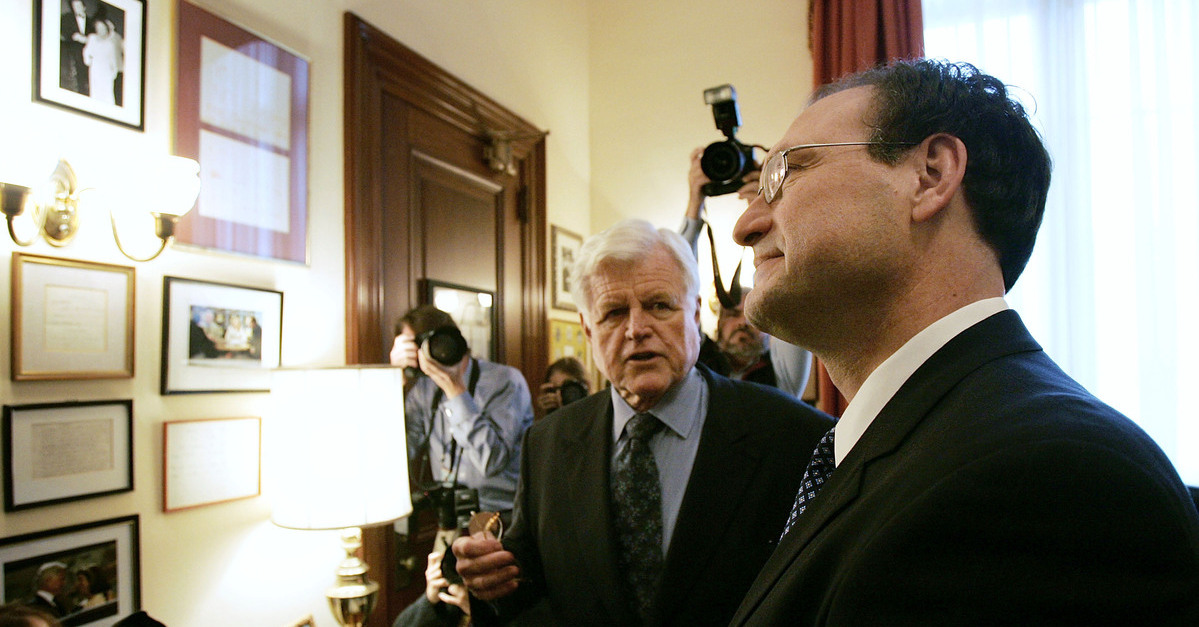

U.S. Supreme Court nominee Samuel A. Alito meets with U.S. Sen. Ted Kennedy (D-MA) as Alito awaits a confirmation hearing that will decide if he becomes a Supreme Court justice.

A new report of a conversation between Associate Justice of the Supreme Court Samuel Alito and Edward “Ted” Kennedy (D-Mass) has highlighted what the justice told the late senator in 2005 and what the justice actually did 17 years later when he wrote the opinion overturning Roe v. Wade.

A New York Times piece by author John A. Farrell (whose book Ted Kennedy: A Life was released Tuesday) revealed details of a private conversation in 2005 between Alito and Kennedy. At the time, when Alito was seeking Senate confirmation of his nomination to the high bench, the senator transcribed details of the conversation and his reactions to it in his personal diary. According to the diary entries, Kennedy met with Alito and the two discussed the future of Roe v. Wade, the 1973 SCOTUS precedent in which the Court ruled that the right to have an abortion is protected under the First Amendment.

According to Kennedy’s diary entry, Alito assured him in response to a question about Roe’s future, “I am a believer in precedents,” and added, “People would find I adhere to that.”

Alito also elaborated in his conversation with Kennedy, “I recognize there is a right to privacy,” and said, “I think it’s settled.”

Certainly, these exchanges between Alito and Kennedy are reminiscent of the kind of verbal jousting the other conservative justices did with questions about Roe at their own hearings.

In 1991, Clarence Thomas vowed to be “impartial” and to approach legal controversies only after “shed[ding] the personal opinions” that could relate to the underlying issues at hand.

Neil Gorsuch, appointed by a president who campaigned on promises to install anti-abortion justices, said at his confirmation hearing in 2017 that he refused to take a position on Roe. Gorsuch told Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.) that he “would have walked out the door” if Donald Trump specifically asked him to overturn Roe prior to his appointment.

Gorsuch repeatedly called precedent, the “anchor of law,” and acknowledged that Roe was a decades-old precedent that had been reaffirmed. Gorsuch also remarked that, “A good judge will consider [Roe] as precedent of the U.S. Supreme Court worthy as treatment of precedent like any other.”

The next year, Brett Kavanaugh repeated both Thomas’ and Gorsuch’s boilerplate and told the committee that he would be open-minded and that he considered Roe “settled as a precedent.” At the time, Sen. Susan Collins (R-Maine) said she met privately with Kavanaugh and that he specifically said he considered Roe to be “settled law.”

Amy Coney Barrett gave perhaps the strongest indication of Roe’s eventual fate during her 2020 confirmation hearings when she said she did not consider Roe to be a “super precedent.” Barrett did say, however, that she would not “pre-commit” to having a predetermined agenda as a justice.

While the nominees’ responses might have appeared to indicate an unwillingness to revisit the Roe ruling on abortion, those familiar with Supreme Court history likely have always interpreted them otherwise. Assurances that Roe constituted a “settled precedent” were more accurately understood as an acknowledgment that Roe was the controlling law at that moment — and not a declaration that Roe could never be overturned. After all, Plessy v. Ferguson, Hammer v. Dagenhart, and Bowers v. Hardwick were all at one time “settled precedent.”

Ted Kennedy would have been well aware in 2005 that judicial nominees deliver carefully-crafted and technically ambiguous responses to inquiries at hearings and in private. It was against that backdrop that Kennedy, a staunch supporter of abortion rights, pressed Alito further on the issue.

Kennedy privately asked Alito about a memo he had written in 1985 when Alito had been working as a lawyer in the Reagan administration Justice Department. The memo unequivocally details a legal strategy for eventually overruling Roe v. Wade.

Alito’s response to Kennedy on this matter was shockingly distinct from Alito’s 2020 words in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, according to the Times report:

Judge Alito assured Mr. Kennedy that he should not put much stock in the memo. He had been seeking a promotion and wrote what he thought his bosses wanted to hear. “I was a younger person,” Judge Alito said. “I’ve matured a lot.”

Kennedy was unconvinced and eventually voted against Alito’s confirmation to the Supreme Court. The senator also specifically noted a key factor in his unwillingness to support Alito: “If the judge could configure his beliefs to get that 1985 promotion…how might he dissemble to clinch a lifetime appointment to the nation’s highest court?”

In the end, of course, Alito did vote to overrule Roe and authored the opinion calling Roe “egregiously wrong from the start.” Despite Alito’s carefully worded assurances to Kennedy that he “recognized” a “settled” right to privacy, the justice rested the majority’s reasoning on the Constitution’s lack of explicit language creating “privacy” as a protected right.

Warming to Justice Barrett’s thinking on “super precedent,” Alito went on to say in the ruling that the diversity of views held by Americans on the subject of abortion is precisely what mandates the subject be returned to state control — a line of logic conspicuously absent from the justice’s exchanges with Kennedy in 2005.

On the matter of stare decisis, Alito’s sentiment in the Dobbs decision bore no relation to his one-time vow to be “a believer in precedents.” In Dobbs, Alito railed against Roe the precedent, calling it a “deeply damaging” and “unworkable” “brainchild” of the 1973 Court, and likened its wrongfulness to that of Plessy v. Ferguson.

[Image via Win McNamee/Getty Images]