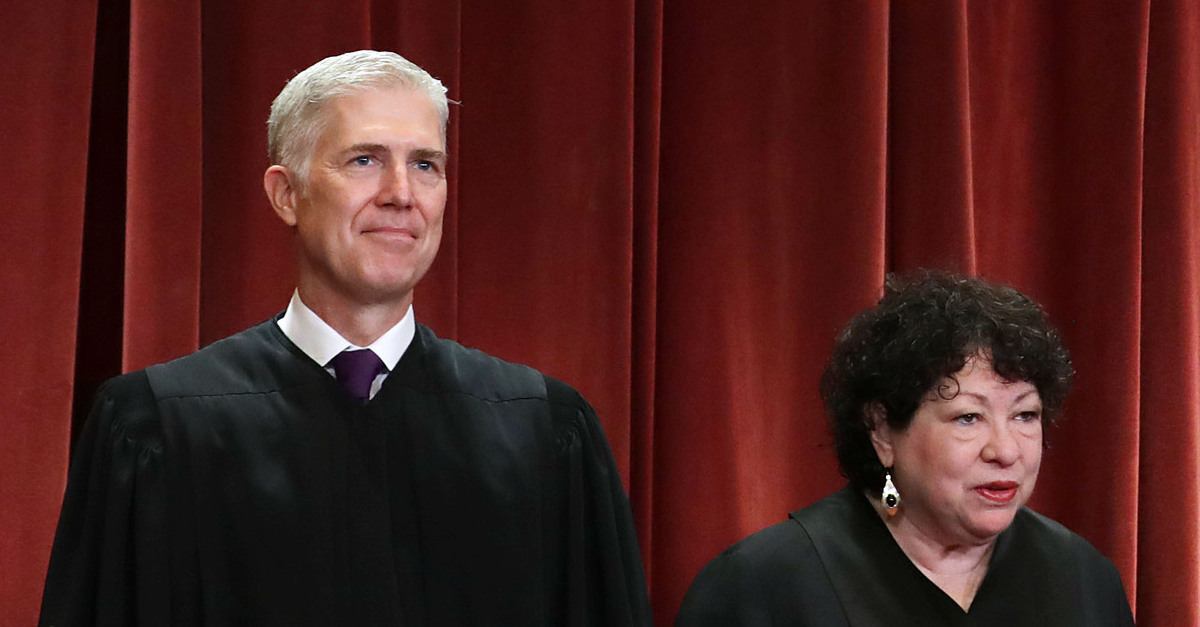

United States Supreme Court Justices Neil Gorsuch (L) and Sonia Sotomayor (R) pictured posing for an official court photo.

The U.S. Supreme Court on Thursday ruled in favor of state Republican Party leaders in a case nominally about a voter identification law that a lower North Carolina court previously found was passed with “racial discrimination” as a “motivating factor.”

Stylized as Berger v. NC Conference of NAACP, the case was decided in favor of GOP state legislators who argued the Tarheel State’s Democratic Attorney General was not “adequately” defending North Carolina Senate Bill 824, which requires a photo ID to vote.

“At the heart of this lawsuit lies a challenge to the constitutionality of a North Carolina election law,” Justice Neil Gorsuch notes at the outset of the 8-1 majority opinion. “But the merits of that dispute are not before us, only an antecedent question of civil procedure: Are two leaders of North Carolina’s state legislature entitled to participate in the case under the terms of Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 24(a)(2)?”

The answer to that question, the majority held, is “Yes.”

Gorsuch takes a long-and-winding jurisprudential drift through: (1) the potential composition of the several states; and (2) the reality of lawsuit stylization in explaining how the result came about.

“States are free to structure themselves as they wish,” the opinion notes.

Eventually, Gorsuch gets to the heart of the matter:

Generally, States themselves are immune from suit in federal court. So usually a plaintiff will sue the individual state officials most responsible for enforcing the law in question and seek injunctive or declaratory relief against them. Despite the artifice, of course, a State will as a practical matter often retain a strong interest in this kind of litigation. After all, however captioned, a suit of this sort can implicate “the continued enforceability of [the State’s] own statutes.” To defend its practical interests, the State may choose to mount a legal defense of the named official defendants and speak with a “single voice,” often through an attorney general.

In the present case, that’s exactly what happened.

The NAACP sued. North Carolina Attorney General Josh Stein (D) was named as a defendant because he’s the state’s top law enforcement official. But, GOP leaders noted, Stein had personally expressed dismay over and opposition to the law while on the campaign trail. The GOP’s theory was that the current trial team simply didn’t have their hearts in defending the law passed by the GOP.

So, led by Berger, the elected officials sued to intervene. A district court ruled in favor of state leaders. A three-judge panel on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit initially sided with the GOP. The whole appellate court then reheard the case and overruled the panel in a 9-6 opinion, siding with the state leaders and the NAACP.

Gorsuch begins with the text of the rule in question:

On timely motion, the court must permit anyone to intervene who…claims an interest relating to the property or transaction that is the subject of the action, and is so situated that disposing of the action may as a practical matter impair or impede the movant’s ability to protect its interest, unless existing parties adequately represent that interest.

Breaking up the analysis, the majority determines the relevant question here is two-pronged: (1) whether state leaders have “claimed an interest in the resolution of this lawsuit that may be practically impaired or impeded” unless they’re allowed to intervene; and (2) whether Stein’s team can “adequately represent” the GOP leaders’ interest.

Dispositive to the first question is a relatively recent North Carolina state law that allows the legislature to intervene in lawsuits such as the one the NAACP filed against the underlying voter law in question.

This law allows the majority to elide the Supreme Court’s general opposition to allowing various categories of litigants.

“[T]he legislative leaders are among those North Carolina has expressly authorized to participate in litigation to protect the State’s interests in its duly enacted laws,” Gorsuch writes – identifying the interest at stake here. “[W]hile the General Assembly has afforded the attorney general considerable authority, it has also reserved to itself some authority to defend state law on behalf of the State.”

This even makes basic legal sense, the majority says, because “a plaintiff who chooses to name this or that official defendant does not necessarily and always capture all relevant state interests.”

Gorsuch explicitly frames the ruling as a way to vindicate the liberal constitutional notion that states “serve as laboratories of ‘innovation and experimentation’ from which the federal government itself may learn and from which a ‘mobile citizenry’ benefits.”

As for the second question, the majority pens a new bright line rule interpreting federal civil procedure: “a presumption of adequate representation is inappropriate when a duly authorized state agent seeks to intervene to defend a state law.”

For Gorsuch, it’s a simple matter of comity.

“Any presumption against intervention is especially inappropriate when wielded to displace a State’s prerogative to select which agents may defend its laws and protect its interests,” the majority explains. “Normally, a State’s chosen representatives should be greeted in federal court with respect, not adverse presumptions.”

This new rule drew particular ire in the dissent by Justice Sonia Sotomayor.

“The Court’s presumption of inadequacy is novel,” she wrote. “Neither petitioners nor the Court identify a single precedent in which a state actor was entitled to intervene as of right to defend a statute that another state actor already was defending.”

Sotomayor would narrowly interpret the federal rule and give it precedence over the state’s litigation-authorizing law:

This result contravenes Rule 24(a)(2) and the practical realities of litigation that it reflects. Federal law gives district courts responsibility to assess, in the first instance, the adequacy of a party’s representation because those courts are most familiar with that representation and are responsible for managing their dockets and streamlining proceedings. Rule 24(a)(2) thus does not require district courts to allow intervention where interests are adequately represented because such intervention would be duplicative and inefficient.

[ERIN SCHAFF/POOL/AFP via Getty Images]