The Supreme Court of the United States heard oral arguments Tuesday in companion cases involving illegal gun possession and the fallout from a recent SCOTUS precedent. The cases are Greer v. United States (on appeal from the Eleventh Circuit) and United States v. Gary (on appeal from the Fourth Circuit).

Both cases ask the justices to clarify the impact of the 2019 landmark case Hamid Rehaif v. United States. In Rehaif, the Court ruled 7-2 in favor of an immigrant who was caught illegally possessing a handgun. Under the federal gun law, Hamid Rehaif would only have been guilty if he “knowingly violated” firearm laws. The case turned on whether the statute required Rehaif to be aware that his gun possession had been illegal [Rehaif had been using a gun at a firing range, ostensibly believing that he was entitled to do so].

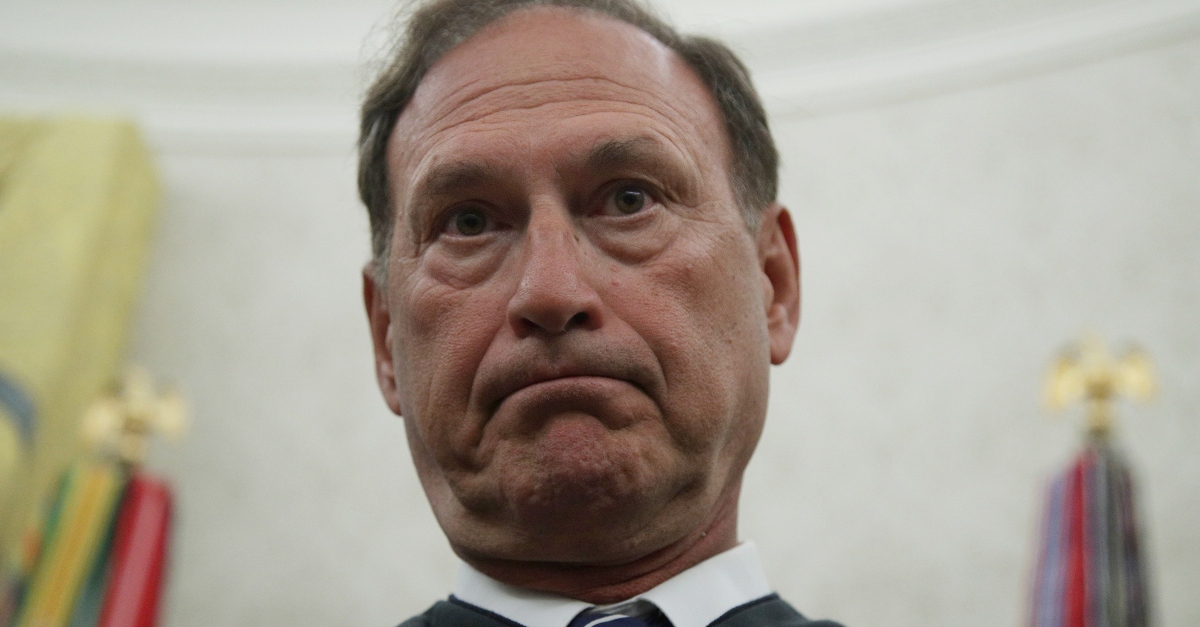

Justice Stephen Breyer wrote for the Court, remarking, “Assuming compliance with ordinary licensing requirements, the possession of a gun can be entirely innocent.” Justices Samuel Alito and Clarence Thomas, however, disagreed. In Alito’s dissent, he warned that the Court’s ruling promises practical effects that “will be far reaching and cannot be ignored.” According to the dissenters, “tens of thousands of prisoners” would now have cause to appeal their convictions, even though many of them had pleaded guilty.

Gregory Greer and Michael Andrew Gary may be just two of those “tens of thousands.” Both cases involve facts markedly different from those in Rehaif, but what those differences mean for these defendants remains to be seen.

Greer, a five-time felon, had run from officers outside a hotel room. He sprinted away, tossing a heavy object into a stairwell landing. Cops later found a Colt .45 caliber pistol, then captured Greer, who had empty nylon holster in his waistband. He was convicted of illegal gun possession; on appeal, the Circuit Court applied a “plain error” test, and determined that it was not clear that errors in Greer’s indictment or trial deprived him of any substantial rights. Greer now argues that the Eleventh Circuit incorrectly based its ruling on a review of a pre-sentencing report — which had not been introduced at Greer’s trial.

Gary pleaded guilty to federal felony possession of a firearm; at the hearing, he admitted he knew it was wrong for him to have a firearm. However, Gary had not been specifically informed that the government needed to prove his specific knowledge of the wrongful possession.

Greer and Gary both argue that SCOTUS’s ruling in Rehaif entitles them to reversals of their convictions.

The justices were overtly skeptical of the defense argument in Greer, as articulated by Assistant Federal Defender M. Allison Guagliardo. Responding to Guagliardo’s argument that the Eleventh Circuit relied on improper information in ruling against Greer, Justice Thomas queried, “Do you have any doubt in this case that the government would have preferred to introduce the evidence that you say is lacking here?”

Thomas went even a step farther, criticizing the underlying logic of Guagliardo’s argument and remarking, “Your approach would put someone who stipulates in a better position than someone who actually went to trial.”

Justice Breyer, who authored the Rehaif opinion, seemed to be look for a way to limit any fallout. Breyer pressed Greer’s attorney on her argument that the appellate court should not have considered facts outside the trial record. “Why only look at the trial record?” he asked, before posing a number of hypotheticals. “There could have been something that happened before the trial [that is] an error,” the justice noted. “There could be something on the list of witnesses, there could be a limitation on what’s asked,” Breyer continued. “The possibilities are endless. So where does this idea come from you can only look at certain things?” he asked. “I’m totally at sea as to why or how to draw some line,” he told Guagliardo.

Finally, demonstrating concern for just the kind of deluge of appeals Alito warned about in Rehaif, Breyer concluded his remarks by saying, “I fear that we start getting into the rule-making in this area… Do you see what I’m afraid of? A mess.”

Even Justice Sonia Sotomayor, who is often receptive to criminal defense arguments, appeared unconvinced by Greer’s argument. The justice began her questions by saying, “Counsel, I think Justice Scalia would have agreed with you” — a sure sign that she would think differently.

Returning to the facts of Greer’s case and the requirement that he knew he had been violating the statute, Sotomayor said, “Your defendant was just released from prison six months before he was arrested for this charge and he had served either 20 months or 36 months. It’s impossible to believe that there’s any reasonable doubt that he could have put his knowledge in contention.”

Assistant to the Solicitor General Benjamin Snyder argued on behalf of the Department of Justice, and the justices received his arguments with noticeably less skepticism. The justices fired multiple hypotheticals at Snyder, raising questions of when it might be appropriate for an appellate court to look beyond the trial record in cases like Greer’s.

Snyder concluded his remarks to the Court with a blunt statement of his case: “Our rule would allow courts to evaluate all of the available evidence and grant case-specific relief whenever it would be genuinely unfair.” By contrast, Snyder finished, “if [Greer] had a plausible argument about why that sentencing evidence was unreliable or didn’t tell the whole story, he’d be free to make that argument, but he has no right to ask a court to pretend that evidence doesn’t exist.”

Gary’s attorney, Jeffrey L. Fisher, argued that the case required automatic reversal because failing to advise the defendant of the complete charges against him deprives him of the ability to “knowingly and intelligently” make the “grave choice” between going to trial and choosing to accept a plea deal and surrendering one’s liberty.

“Indeed it would trample the framers’ vision of free will to enforce a guilty plea where the only facts admitted do not even constitute a crime and where having been advised of the true nature of the charge the defendant wants to continue,” Fisher said in his opening remarks.

The justices seemed similarly skeptical of Fisher’s case, with many noting that it could have widespread effects on existing convictions.

Speaking about the proposition that an individual’s felony status “is not the kind of thing that one forgets,” Justice Brett Kavanaugh said “from that premise it seems odd to throw out all of the convictions” and asked Fisher if he believed that premise to be true.

“The question shouldn’t be whether defendants are typically aware of the element or the element is typically satisfied, the question should be whether the defendant when he pleads guilty understood that that was part of the charge and therefore was given an opportunity to exercise his own free will,” Fisher responded.

Fisher closed by saying the case involved the “most fundamental of principles and the most sensitive of practices: a conviction without a trial.”

DOJ attorney Jonathan Ellis rebutted Fisher, saying that what he was requesting was either “a highly gerrymandered rule in this case or one that would affect a sea change.”

[Image via Alex Wong_Getty Images]