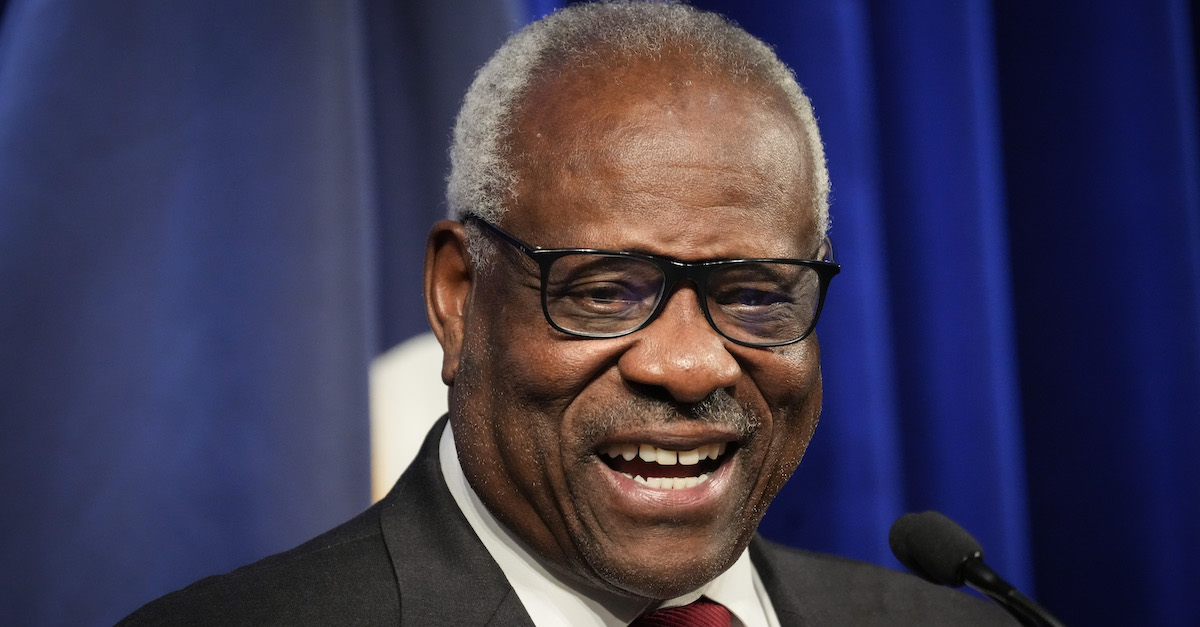

Associate Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas

Justice Clarence Thomas led a six-member conservative majority of the Supreme Court of the United States in a ruling that two Arizona death-row inmates may not raise evidence of their lawyers’ ineffective assistance in their federal habeas corpus petitions. The case is stylized as Shinn v. Ramirez, and it is an appeal from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit.

Convicted capital murderers David Martinez Ramirez and Barry Lee Jones sought post-conviction relief in federal court after their state court claims were denied. Both men hoped to prove that deadlines missed in state court might be excused based on the carelessness of their court-appointed lawyers.

Justice Thomas authored the opinion of the court, which broke down along the usual ideological lines.

As is often Justice Thomas’s practice, the opinion began with a recounting of the gruesome facts underlying the defendants’ convictions: Ramirez fatally stabbed his girlfriend, Mary Ann Gortarez, 18 times in the neck with a pair of scissors, and raped Gortarez’s 15-year-old daughter, Candie Gortarez, and stabbed her in the neck with a box cutter, killing her; Barry Lee Jones was convicted and sentenced to death for the 1994 sexual assault and murder of his girlfriend’s 4-year-old daughter, Rachel Gray.

After each defendant was convicted for his crimes, appeals in state court followed. When those appeals were denied, each attempted a federal habeas corpus petition. In both cases, the U. S. District Court for the District of Arizona denied the petitions on the grounds that the petitioners failed to raise a timely claim in state court.

Ramirez and Jones argued that whatever procedural errors had occurred should not be held against them, because their attorneys at the post-conviction phase had been ineffective. In both cases, the district court allowed the petitioners to introduce evidence to support the claim of ineffective assistance of counsel.

The State of Arizona appealed and challenged the district court’s decision to allow the introduction of evidence to support the petitioners’ claim. On appeal, the Ninth Circuit sided with the petitioners, and allowed the additional evidence. Arizona appealed again, and this time, found SCOTUS’s conservative justices to be a friendly bench.

Thomas characterized the ruling as one that’s, at its core, a win for states’ rights. Using federal habeas corpus to overturn a state conviction, “is to inflict a profound injury to the powerful and legitimate interest in punishing the guilty, an interest shared by the State and the victims of crime alike,” quoted Thomas from a 1998 case.

Thomas also had some practical concerns. Legal proceedings are costly, he noted: “If the state trial is merely a ‘tryout on the road’ to federal habeas relief, that ;detract[s] from the perception of the trial of a criminal case in state court as a decisive and portentous event.'”

Furthermore, wrote Thomas, habeas corpus is an extraordinary remedy, and one that always lies within the court’s discretion.

“[T]o allow a state prisoner simply to ignore state procedure on the way to federal court would defeat the evident goal of the exhaustion rule,” Thomas warned.

Rather, federal courts should hesitate to interfere with state convictions “Out of respect for finality, comity, and the orderly administration of justice,” Thomas write, quoting a 2004 case.

Thomas reasoned that his reading of federal law and relevant precedent dictates that any ineffectiveness on the part of a post-conviction lawyer in developing the state-court record “is attributed to the prisoner,” and thus, not a ground for excusing deadlines. Thomas rejected the argument that he characterized as advocating for “largely unbounded access to new evidence.”

The justice pointed to the Jones case as an example, saying that the “sprawling evidentiary hearing” in the case was “particularly poignant.” There, the court conducted “a 7-day hearing that included testimony from no fewer than 10 witnesses, including defense trial counsel, defense post conviction counsel, the lead investigating detective, three forensic pathologists, an emergency medicine and trauma specialist, a biomechanics and functional human anatomy expert, and a crime scene and bloodstain pattern analyst.” This lengthy witness list testified about “virtually every disputed issue in the case,” in what Thomas called a “wholesale relitigation of Jones’ guilt.”

Ending right where he began — at state sovereignty — Thomas concluded his 22-page opinion with harsh words for the idea of using federal habeas corpus to essentially second-guess a state court ruling:

Such intervention is also an affront to the State and its citizens who returned a verdict of guilt after considering the evidence before them. Federal courts, years later, lack the competence and authority to relitigate a State’s criminal case

Justice Sonia Sotomayor penned the 20-page dissent, which was predictably joined by Justices Stephen Breyer and Elena Kagan. Sotomayor laid her dissent squarely at the feet of the Sixth Amendment, writing:

Today, however, the Court hamstrings the federal courts’ authority to safeguard that right. The Court’s decision will leave many people who were convicted in violation of the Sixth Amendment to face incarceration or even execution without any meaningful chance to vindicate their right to counsel.

In stark contrast with Thomas’ argument that the majority’s ruling fell in line with the true meaning of past precedent, Sotomayor said the 6-3 decision “all but overrules two recent precedents.”

Sotomayor continued her dissent, and called the majority’s decision “perverse” and “illogical.” She also jabbed at Thomas’s recounting of the horrific facts of the underlying crimes.

“The majority sets forth the gruesome nature of the murders with which respondents were charged,” Sotomayor wrote. “Our Constitution insists, however, that no matter how heinous the crime, any conviction must be secured respecting all constitutional protections.”

Throwing in some facts of her own, Sotomayor noted that Jones’s “trial counsel failed to undertake even a cursory investigation.” As a result, the jury never heard the “readily available medical evidence” that could have shown that the child victim sustained her injuries while in another person’s care. To make matters worse, both Jones’s trial lawyer and his post-conviction lawyer failed to meet the minimum qualifications that Arizona usually requires in capital cases.

Ramirez’s lawyer failed to provide evidence that his client had an intellectual disability and suffered long-term child abuse, both of which would have mitigated against the imposition of a death sentence.

Sotomayor went on to explain that “Ineffective-assistance claims frequently turn on errors of omission.” As such, the justice said, proof that counsel failed to investigate or procure evidence “by definition requires evidence beyond the trial record.”

She disagreed specifically with the majority’s reasoning that the federal Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act (AEDPA) precluded the kind of evidence Jones and Ramirez sought to introduce. The majority has it backward, according to Sotomayor; AEDPA does not “categorically prioritize[] maximal deference to state-court convictions over vindication of the constitutional protections at the core of our adversarial system.” While federalism is important, it does not pursue its aims “at all costs.”

Sotomayor expounded on her view of the underlying injustice at stake in the case:

On the other side of the ledger, the Court understates, or ignores altogether, the gravity of the state systems’ failures in these two cases. To put it bluntly: Two men whose trial attorneys did not provide even the bare minimum level of representation required by the Constitution may be executed because forces outside of their control prevented them from vindicating their constitutional right to counsel. It is hard to imagine a more “extreme malfunctio[n],” than the prejudicial deprivation of a right that constitutes the :foundation for our adversary system.”

Following the Court’s ruling Monday, several court watchers immediately commented on the dangers of SCOTUS’s decision.

University of Texas Law professor Lee Kovarsky said in a tweet, “Indigent representation in the United States sucks, we all know this,” and pointed out the inherent conflict of an attorney seeking an ineffective assistance of counsel claim against themself.

Kovarsky also gave context for court-appointed post-conviction attorneys generally. He tweeted, “It’s like, ‘you got a shitty lawyer at trial, well congratulations your new attorney is someone who would be lucky to be their summer intern.'”

University of Texas Law professor Steve Vladeck called the Court’s ruling “a big deal in real — and not just doctrinal — terms.”

University of Michigan Law professor Leah Litman summarized the ruling’s expected effects on the indigent, tweeting: “If the state appoints you a lawyer who is constitutionally ineffective at your trial; and then appoints you ANOTHER lawyer who is constitutionally ineffective to argue your trial lawyer was ineffective … you’re screwed.”

Mark Joseph Stern of Slate warned, “this decision effectively ensures that innocent people will remain imprisoned.”

“I’m having a hard time finding the words to express how terrible the Court’s decision (by Justice Thomas) is in Shinn v Ramirez. Thankful that Justice Sotomayor’s dissent captures it,” Director-counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund Sherrilyn Ifill added.

The court’s ruling in Shinn v. Ramirez is one of two rulings handed down by the Supreme Court on Monday that involved death row inmates in the State of Arizona. In the other case, Smith v. Shinn, SCOTUS denied certiorari on a petition filed by Joe Clarence Smith. Smith has been on Arizona’s death row for 44 years, and is one of the longest-serving death row inmates in the country.

[image via Drew Angerer/Getty Images]