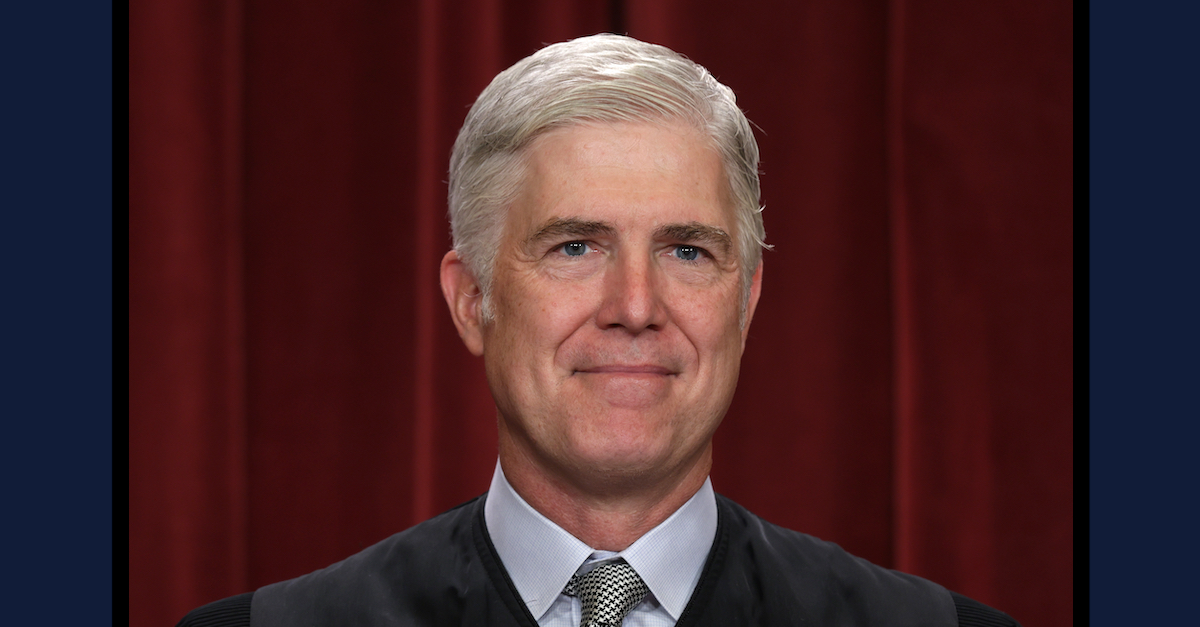

Justice Neil Gorsuch poses for an official portrait in the East Conference Room of the Supreme Court building on October 7, 2022 in Washington, D.C. (Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images.)

The Supreme Court ordered the federal government to continue enforcing severe immigration restrictions put in place during the brunt of the COVID-19 pandemic, inspiring strange bedfellows on the bench between Justices Neil Gorsuch and Ketanji Brown Jackson.

In a joint dissent, the pair argued that the court’s conservative 5-4 majority substituted its preferred policy outcome for what the law required.

“The States contend that they face an immigration crisis at the border and policymakers have failed to agree on adequate measures to address it,” the dissent states. “The only means left to mitigate the crisis, the States suggest, is an order from this Court directing the federal government to continue its COVID-era Title 42 policies as long as possible — at the very least during the pendency of our review. Today, the Court supplies just such an order.”

The battle relates to the application of Title 42 of the Public Health Services Act, which allows the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to block people from entering the United States to stop the spread of communicable diseases.

Former President Donald Trump invoked the law to curb legal immigration at the U.S.-Mexico and U.S.-Canada borders in March 2020, to outcry from advocates who called the policy “inhumane.” It has been used since that time to expel asylum-seekers from the United States without a hearing.

After President Joe Biden‘s administration announced plans to discontinue the policy in April 2021, a group of Republican state attorneys general — led by the state of Arizona — sued. The litigation has meant that the harsh Title 42 restrictions never lapsed.

Multiple court battles ensued, with different outcomes. In Louisiana, U.S. District Judge Robert Summerhays, a Trump appointee, issued a nationwide injunction forcing the administration to continue enforcing the policy in May 2021. In Washington, D.C., U.S. District Judge Emmet Sullivan, a Bill Clinton appointee, found the application of Title 42 “arbitrary and capricious,” ordering the Biden administration to halt the policy.

On Dec. 19, Chief Justice John Roberts issued an emergency stay of Sullivan’s order, while the rest of the justices considered their next steps.

Minus Gorsuch, the high court’s conservative wing found that the stay should stand pending adjudication. Gorsuch, Jackson, and the Supreme Court’s left flank found that was a mistake, even if Gorsuch added that he did not “discount” the states’ concerns.

“Even the federal government acknowledges ‘that the end of the Title 42 orders will likely have disruptive consequences,'” the dissent states. “But the current border crisis is not a COVID crisis. And courts should not be in the business of perpetuating administrative edicts designed for one emergency only because elected officials have failed to address a different emergency. We are a court of law, not policymakers of last resort.”

Gorsuch added that the global state of emergency under which the Title 42 policy was invoked has passed.

“The States may question whether the government followed the right administrative steps before issuing this decision (an issue on which I express no view),” he continued. “But they do not seriously dispute that the public-health justification undergirding the Title 42 orders has lapsed. And it is hardly obvious why we should rush in to review a ruling on a motion to intervene in a case concerning emergency decrees that have outlived their shelf life.”

The American Civil Liberties Union’s attorney Lee Gelernt, who is leading the challenge, said he will continue to fight.

“The Supreme Court has allowed Title 42 to remain in place temporarily while the case is ongoing, and we continue to challenge this horrific policy that has caused so much harm to asylum seekers and cannot plausibly be justified any longer as a public health measure,” Gelernt wrote in a statement.

Trial attorney David R. Lurie, a frequent legal commentator, interpreted Gorsuch’s dissent as a sign of him being “focused on the project of weakening certain presidential powers.”

“Gorsuch does recognize that sometimes even audaciously partisan jurists need to be somewhat ideologically consistent — in this case in order to further their broader project to weaken presidential regulatory power,” he added.