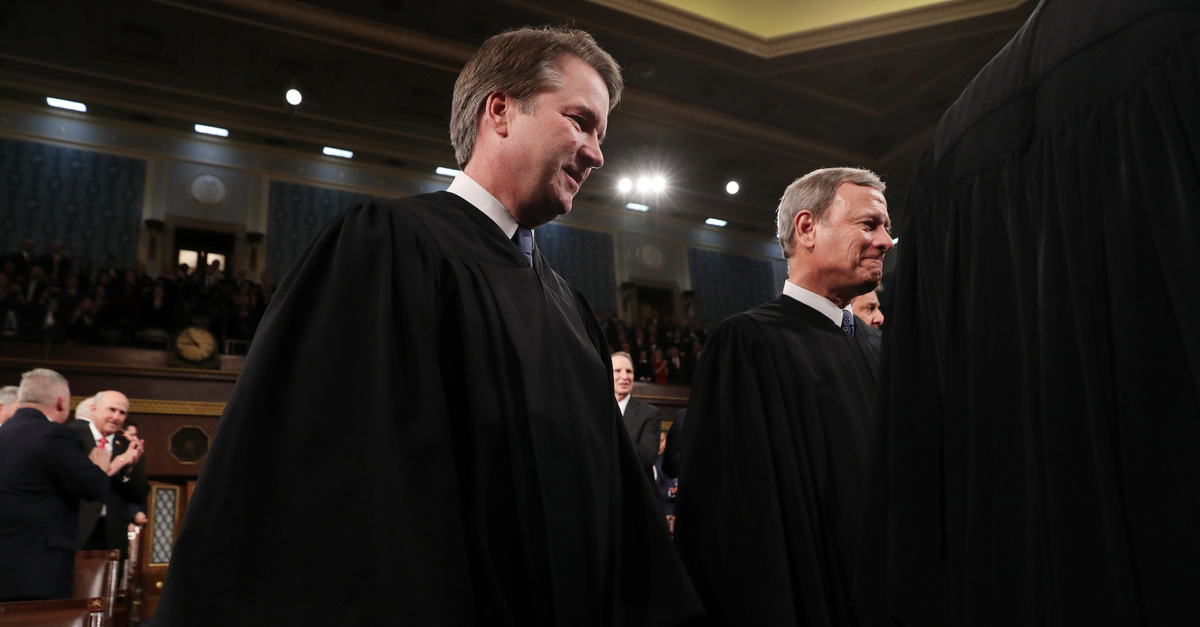

A key provision of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) survived the scrutiny of the U.S. Supreme Court on Monday in a decision that saw Chief Justice John Roberts and conservative Justice Brett Kavanaugh side with the court’s liberal wing, the second such instance in a matter of days.

Authored by Justice Sonia Sotomayor, the high court ruled in favor of health insurance companies who are seeking to recoup losses incurred by Obamacare’s Risk Corridors program–a since-expired portion of the law that promised companies the government would foot the bill for particularly unprofitable plans during the first three years of the health insurance marketplace.

When the law was passed, §1342 contained a complex formula that determined profitability and mandated that the federal government “shall pay” insurance companies when a certain amount of losses are incurred. The provision also provided that those same companies “shall pay” the federal government if certain profits are achieved.

“Some plans made money and paid the Government,” the court noted. “Many suffered losses and sought reimbursement. The Government, however, did not pay.”

Those false promises prompted several chains of litigation. Four insurance companies sued the federal government seeking hundreds of millions of dollars in lost profits. One of the insurance companies proved successful in the lower courts. Three of the companies were not successful–prompting a split that the Supreme Court decided in their favor–a decision which is likely to augur well for the continued constitutional viability of the ACA in general.

“We conclude that §1342 of the Affordable Care Act established a money-mandating obligation, that Congress did not repeal this obligation, and that petitioners may sue the Government for damages,” Sotomayor wrote.

The plain language of the statute in question was complicated by the fact that the landmark health care law did not allocate specific funds for the purposes of paying the companies negatively impacted by the Risk Corridors program. Further complicating the issue was how Congress chose to deal with the program’s deficit.

For each of the three years at issue, riders attached to appropriations bills explicitly limited the ability for those companies to be repaid.

The exact same rider was used each time:

None of the funds made available by this Act from the Federal Hospital Insurance Trust Fund or the Federal Supplemental Medical Insurance Trust Fund, or transferred from other accounts funded by this Act to the “Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services–Program Management” account, may be used for payments under section 1342(b)(1)of Public Law 111-148 (relating to risk corridors).

In essence, the above language functioned as a poison pill amendment in several funding bills that the U.S. political establishment typically considers–and considered–to be “must pass legislation.” Critics were frequently wont to note that congressional Republicans were effectively sabotaging Obamacare.

“[T]he insurance companies were thrown into a crisis,” author Thom Hartman noted in a representative piece from March 2017 for Alternet. “And, with Republicans in Congress absolutely refusing to re-fund the risk corridors, that crisis would get worse as time went on, at least over a period of a few years.”

“So the insurance companies did the only things they could,” Hartman continued. “In (mostly red) states with low incomes and thus poorer health, they simply pulled out of the marketplace altogether. This has left some states with only one single insurer left. In others, they jacked up their prices to make up their losses.”

In sum, the deficits incurred by the Risk Corridors program exceeded $12 billion. And, while the damage to the framework of the ACA was long-ago complete and contained (due to the program’s expiration), the insurance companies are still looking to see themselves made whole and for Congress to keep its word.

“They alleged that §1342 of the Affordable Care Act obligated the Government to pay the full amount of their losses as calculated by the statutory formula and sought a money judgment for the unpaid sums owed—a claim that, if successful, could be satisfied through the Judgment Fund,” Sotomayor wrote, citing a “a permanent and indefinite appropriation” in federal law that is meant to satisfy final judgments in civil lawsuits when no other funds are available or otherwise specifically outlaid.

The decision clearly elucidated its reasoning:

Section 1342 imposed a legal duty of the United States that could mature into a legal liability through the insurers’ actions—namely, their participating in the healthcare exchanges. This conclusion flows from §1342’s express terms and context. The first sign that the statute imposed an obligation is its mandatory language: “shall.” “Unlike the word ‘may,’ which implies discretion, the word ‘shall’ usually connotes a requirement.” Section 1342 uses the command three times: The HHS Secretary “shall establish and administer” the Risk Corridors program from 2014 to 2016, “shall provide” for payments according to a precise statutory formula, and “shall pay” insurers for losses exceeding the statutory threshold.

Aside from the specific matter at hand, the decision also provided a sure-to-be seized upon rule of constitutional exposition.

“Put succinctly, Congress can create an obligation directly through statutory language,” Sotomayor observed.

The 6-3 opinion was also joined by conservative Justice Neil Gorsuch as well as arch-conservative Justice Clarence Thomas, but both refused to join in a portion of the opinion that dismissed the government’s use of legislative history to support their anti-payments argument.

In a relatively muted dissent, conservative Justice Samuel Alito warned that the court’s ruling may open the floodgates of “private rights of action not expressly created by Congress.”

[T]he Court infers a private right of action that has the effect of providing a massive bailout for insurance companies that took a calculated risk and lost,” Alito said. “These companies chose to participate in an Affordable Care Act program that they thought would be profitable.”

“Not only will today’s decision have a massive immediate impact, its potential consequences go much further,” the dissent continued. “The Court characterizes provisions like §1342 as ‘rare,’ but the phrase the ‘Secretary shall pay’––the language that the Court construes as creating a cause of action––appears in many other federal statutes.”

[image via Leah Millis-Pool/Getty Images]