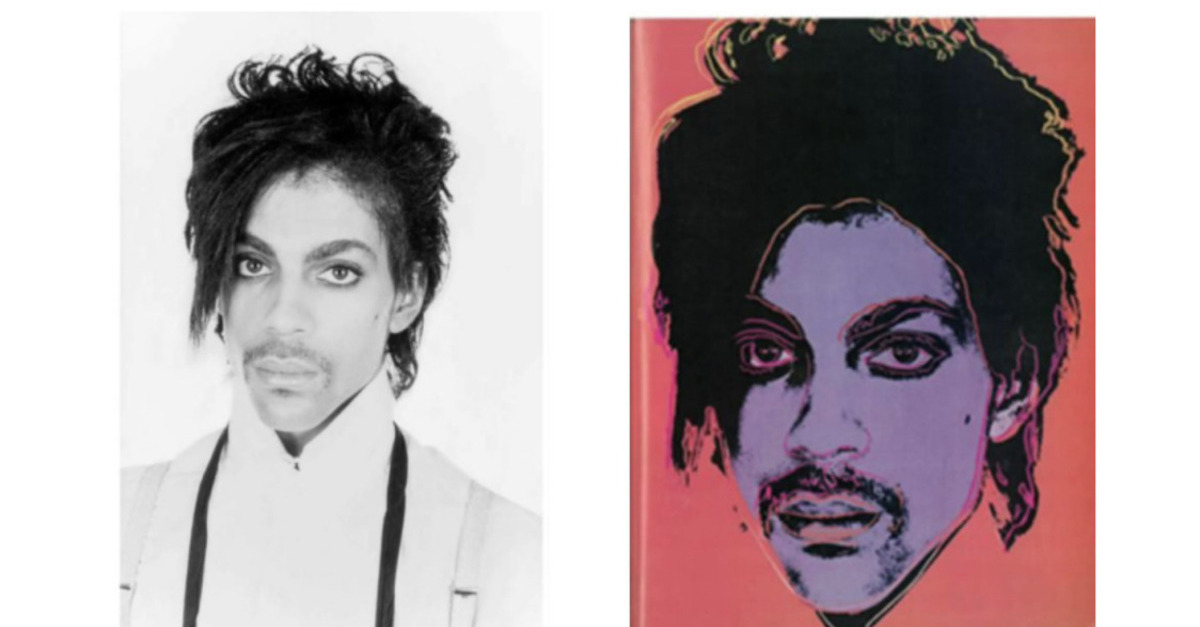

Left: Lynn Goldsmith’s 1981 photograph of Prince, which was a basis for Warhol’s image, Right, Warhol’s “Purple Prince” image.

The Supreme Court of the United States considered the future of the copyright “fair use” doctrine Wednesday in a case that involves three renowned artists: photographer Lynn Goldsmith, visual artist Andy Warhol, and the star musician Prince.

Goldsmith is a celebrity portrait photographer, well known for taking iconic photographs of rock stars that are often used on magazine covers. In 1981, Goldsmith photographed Prince, and Vanity Fair magazine licensed the photo for a $400. Vanity Fair then sent Warhol the Goldsmith photo and asked him to use it as part of an illustration of Prince for use on a future magazine cover.

Warhol made changes to Goldsmith’s photo in his artwork. He cropped the image to remove Prince’s torso, resized it, altered the angle of Prince’s face, and changed tones, lighting, and detail. The result was a mask-like image of Prince titled “Purple Prince.” Warhol also created fifteen additional similar images of Prince.

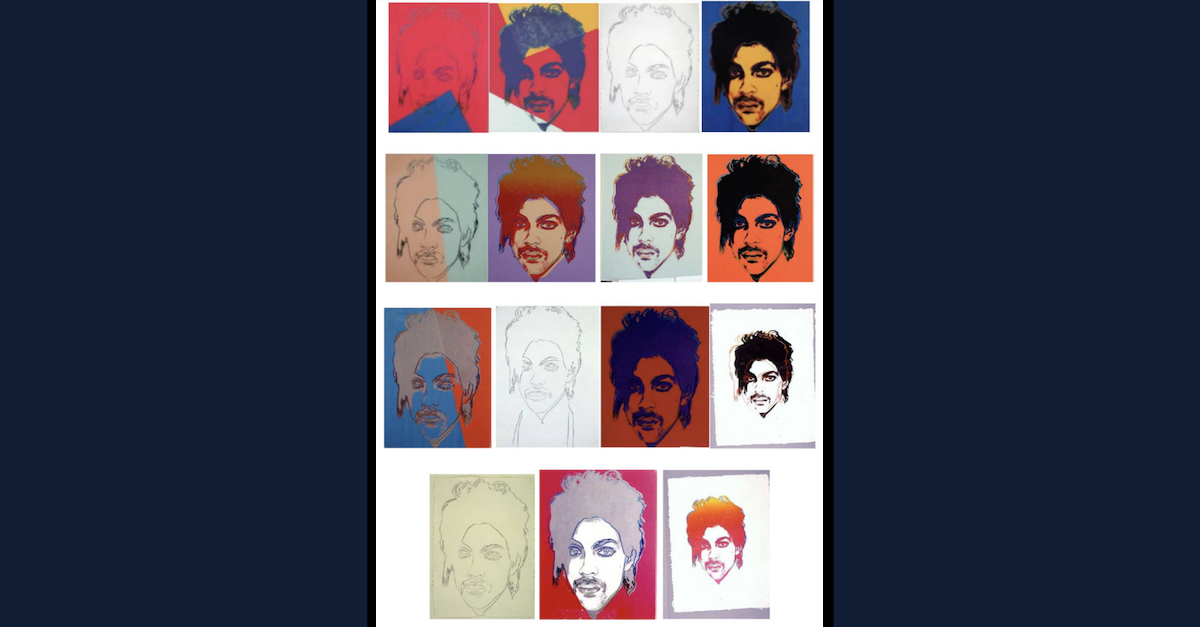

Warhol’s 1984 “Prince Series,” using Goldsmith photos as source materials.

Warhol’s collection of 1984 works, called the “Prince Series,” has been displayed in numerous museums, galleries, and public places since its creation. Warhol died in 1987, and Prince died in 2016. Shortly after Prince’s death, Condé Nast (Vanity Fair‘s parent company) published a tribute issue with one of Warhol’s Prince images as the cover art. The image used, however, was not “Purple Prince,” but rather, “Orange Prince,” pictured above in Row 2, far right.

Condé Nast paid the Andy Warhol Foundation $10,250 to license the image of Warhol’s work. Goldsmith, however, was not paid for the magazine’s use of “Orange Prince.”

At issue in the litigation is whether Warhol’s use of Goldsmith’s photo constituted “fair use” — a copyright-specific legal term of art. If it was fair use, then the Andy Warhol Foundation (the copyright owner for Warhol’s work) is not obligated to pay Goldsmith for usage.

A directly relevant SCOTUS precedent is another high-profile fair use case: the 1994 decision in which the high court held that 2 Live Crew’s hip-hop parody of Roy Orbison’s “Oh Pretty Woman” was a fair use. In the opinion, SCOTUS reasoned in part that parodies necessarily require some degree of copying of the original work in order to function as effective parodies.

The district court ruled in Warhol’s favor, finding that the copying did indeed constitute fair use, because Warhol’s art was sufficiently “transformative” that it conveyed different messaging from Goldsmith’s original photo. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, however, reversed.

The Second Circuit reasoned that what really mattered was that the Prince Series “recognizably deriv[ed] from, and retain[ed] the essential elements” of Goldsmith’s original. That court further held that when derivative works serve the same “function,” they cannot be considered “transformative” for purposes of fair use unless they “sufficiently obscure the ‘foundation upon which [they are] built.'”

The case has garnered significant attention in the art and academic world, with dozens of amicus briefs being filed in support of both parties.

During oral arguments Wednesday, the justices posed questions to tease out the parties’ positions on how, exactly, a court should go about deciding what derivative art constitutes fair use.

Justice Clarence Thomas started off the proceedings by asking attorney Roman Martinez (representing the Andy Warhol Foundation) if any derivative work would fail his proposed test. Martinez gave the example of a book-to-movie adaptation, which would typically not constitute fair use and would therefore require licensing.

A skeptical Justice Sonia Sotomayor pressed Martinez at length, raising concerns about adopting a standard that might be difficult to manage.

“Derivative works are generally in a different medium,” said Sotomayor, “And almost all of them —even a dramatization in theater or a motion picture or sequel—they add something new.”

“So why shouldn’t they be protected as well?” the justice asked.

Justice Samuel Alito raised concerns about the Supreme Court adopting too complex a system of rules, and asked whether fair use cases would end up requiring input from art critics or just artists themselves to determine their “message or meaning.”

“If you called Andy Warhol as a witness, what would he say was the message or meaning of his creation?” asked Alito, pointing out a problem with such a standard.

Justice Elena Kagan raised the concern of subjectivity in art, and asked Martinez if his position might benefit “from a certain kind of hindsight.”

“Now, we know who Andy Warhol was,” Kagan said.

She continued:

It’s easy to say that there is something importantly new with what he did with this image, but if you imagine Andy Warhol as a struggling artist… you might be tempted to say, ‘I don’t get it. All he did was take someone else’s photograph and put some color into it.’We can’t always count on the fact that Andy Warhol is Andy Warhol to know how to make this inquiry.

Martinez answered that Kagan’s point was precisely the reason why Warhol’s use of the Goldsmith photo should be deemed fair use. Martinez argued that if the justices side with Goldsmith, new artists will be dissuaded from creating for fear of costly copyright litigation.

As oral arguments continued, the justices seized the opportunity to showcase their own knowledge of arts and entertainment as they led counsel through various hypotheticals.

Chief Justice John Roberts began by asking about Dutch cubist Piet Mondrian and German-American abstract artist Josef Albers who painted “a single color within a frame.”

“Let’s say somebody uses a different color,” Roberts asked. “If you got art critics to come in and say that blue sends a particular message, yellow sends a different one, would that satisfy any claim of copyright violation?”

Justice Thomas turned the conversation back to the iconic subject of Warhol’s disputed picture — and sent the courtroom into gales of laughter.

Thomas posed a hypothetical with some personal details, “Let’s say that I’m both a Prince fan, which I was in the 80s…”

“No longer?” laughed Kagan, interrupting.

“Well…” Thomas hesitated, “Only on Thursday nights.”

Thomas continued, asking whether, as both a Prince and Syracuse University fan, a poster of Orange Prince changed to say “Go Orange!” underneath and distributed at a Syracuse event would constitute infringement.

Justice Amy Coney Barrett offered an artistic example of her own: in a book-to-movie adaptation, such as Lord of the Rings, would the only relevant inquiry regarding the work’s “transformative” nature be whether the “meaning or message” changes from the original?

Martinez appeared to dismiss the relevance of Barrett’s example, “I don’t think Lord of the Rings has a fundamentally different meaning or message,” but allowed, “I would probably have learn more and read the books and see the movies.”

Barrett exclaimed, “the movie?” laughing.

Martinez allowed, “I recognize reasonable people could probably disagree on that.”

When attorney Lisa Blatt took the podium on behalf of Goldsmith, the colloquy with the justices alternated between fiery and jovial.

“What is the reason or justification to take another’s copyrighted work?” Blatt demanded in her opening argument. Blatt argued that while petitioners emphasize Warhol’s status as a “creative genius,” that “Spielberg did the same for films and Jimi Hendrix for music. Those giants still needed licenses,” she said forcefully. A ruling in the Warhol Foundation’s favor, said Blatt, would mean that, “copyrights will be at the mercy of copycats.”

Blatt continued, arguing that she found the Second Circuit’s opinion, “insulting” to members of the panel of judges who made an earlier ruling.

When the justices chuckled at Blatt’s characterization, she snapped, “I can just keep reading you quotes, but you know how to read a decision as best as I do.” Blatt then slammed the Second Circuit for “yakking” about the relevant law.

The chief justice helpfully summarized the opposing argument and provided context about Warhol’s messaging.

“It’s not just that Warhol has a different style,” said Roberts. “It’s that unlike Goldsmith’s photograph, Warhol sends a message about the depersonalization of modern culture and celebrity status.”

“It’s not just a different style , it’s a different purpose,” Roberts continued. “One is a commentary of modern society, the other is to show what Prince looks like.”

An awkward moment came when Blatt argued that allowing great latitude for artists to create things like television spin-offs would cause havoc.

“Take All in the Family,” Blatt offered. “Normal Lear would be rolling in his grave right now.” Problematically for Blatt’s example, Norman Lear is still alive at age 100.

The justices gave few clues as to how they might rule in the case. However, the breadth of their questions underscored the complexity of the task before them: to create a workable set of copyright rules that protect artists without stifling the creation of new works.

The case is Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts v. Goldsmith, and you can listen to the full oral arguments here.