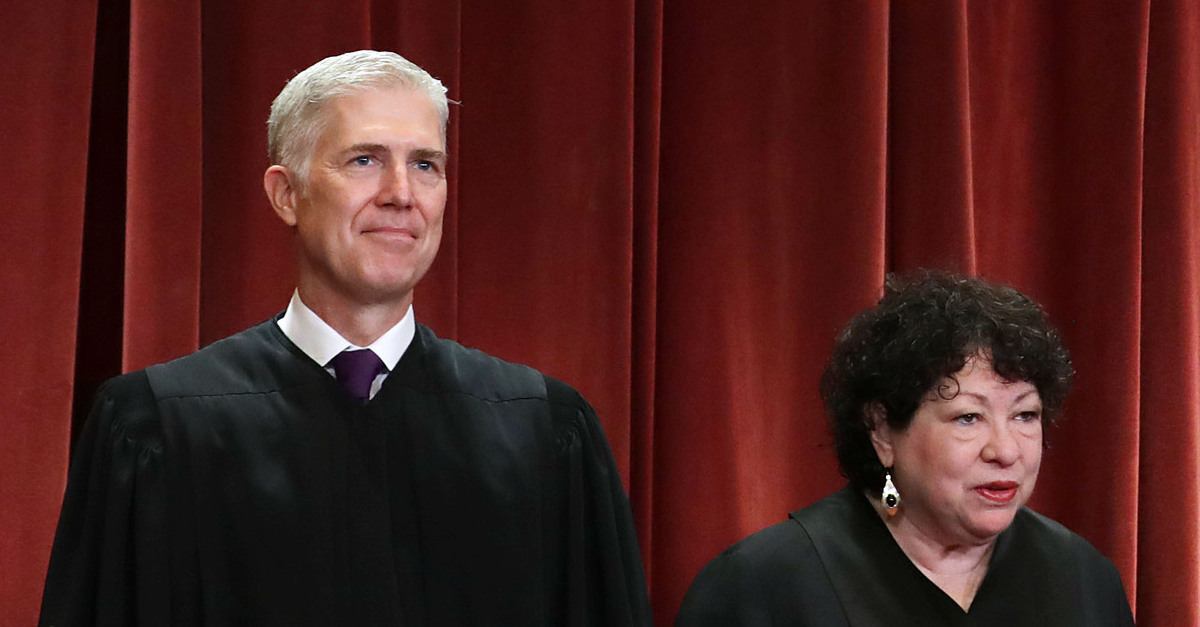

United States Supreme Court Justices Neil Gorsuch (L) and Sonia Sotomayor (R) pictured posing for an official court photo.

Supreme Court Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Neil Gorsuch were unlikely allies Monday as they issued a dissenting statement from the high court’s denial of certiorari in a case demanding transparency over the proceedings conducted by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC) — the judicial body that oversees covert operations conducted by the U.S. intelligence agencies.

A 2016 lawsuit filed by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), Knight First Amendment Foundation, and Yale Law School’s Abrams Institute challenged the FISC’s practice of keeping its opinions completely secret. Eight former government officials, including former CIA Director John Brennan, former Director of National Intelligence James Clapper, and former General Counsel for the Director of National Intelligence Robert Litt, filed amicus briefs urging the Supreme Court to review the case. SCOTUS, however, denied certiorari, effectively ending the petitioners’ current quest for public access to these opinions.

Justice Gorsuch penned a brief but biting dissenting statement which Justice Sotomayor joined. Gorsuch began with a pointed recap of the problem at hand. A congressional committee was convened in 1975 to look into potential wrongdoing by U.S. intelligence agencies. Quoting from the committee’s report, Gorsuch explained that it concluded “that the federal government had, over many decades, ‘intentionally disregarded’ legal limitations on its surveillance activities and ‘infringed the constitutional rights of American citizens.'”

In direct response to those findings, Congress enacted the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978 (FISA), which in turn, created FISC (a court that would oversee electronic surveillance or “FISA Warrants”) as well as the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court of Review (FISCR) (which would hear any appeals from the FISC’s rulings).

Given the ever-expanding role of electronic media in the lives of ordinary individuals, continued the justice, the FISC’s rulings on surveillance programs “carry profound implications for Americans’ privacy and their rights to speak and associate freely. Despite the obvious public interest in FISC’s rulings, however, the court “holds its proceedings in secret and does not customarily publish its decisions.”

In their case, the ACLU and other petitioners asserted that the public has a First Amendment right of access to FISC and FISCR opinions containing significant legal analysis, while also acknowledging that portions of those opinions might require redaction. At issue was not only whether FISC and FISCR should open its opinions for public review, but also whether the courts themselves have the authority to consider the ACLU’s request at all. The ACLU argued that as part of the courts’ inherent powers to manage their own records, they are free to consider the ACLU’s motion.

FISC and FISCR, however, said they had no authority to review the ACLU’s case, and simply refused to go any further. On appeal, the federal government continued in this vein, extending their assertion to argue that the Supreme Court similarly lacks authority to review the ACLU’s motion.

Gorsuch and Sotomayor took issue with both the substance and the procedure of those rulings.

“[T]he government does not merely argue that the lower court rulings should be left undisturbed because they are correct,” Gorsuch wrote. The justice continued, remarking with seeming incredulity, “The government also presses the extraordinary claim that this Court is powerless to review the lower court decisions even if they are mistaken.” Gorsuch continued, pointing out that, “on the government’s view, literally no court in this country has the power to decide whether citizens possess a First Amendment right of access to the work of our national security courts.”

Calling the ACLU’s case one of “grave national importance,” and saying he would have heard the case, Gorsuch ended his dissenting statement by asking, “If these matters are not worthy of our time, what is?”

In a statement reacting to the Court’s ruling, Theodore B. Olson, who served as Solicitor General under former President George W. Bush and is now a member of the Knight Institute’s board, called the Court’s ruling “disappointing,” and said, “It’s crucial to the legitimacy of the foreign intelligence system, and to the democratic process, that the public have access to the court’s significant opinions. Whether the court’s opinions are published should not be up to the executive branch alone to decide.”

Similarly, Alex Abdo, the Knight Institute’s litigation director, said it was “past due” for the Court to demand free access to FISC opinion, and said, “Without access to the FISC’s opinions, the public cannot evaluate the powers that the government’s surveillance agencies are exercising in its name.”

“By turning away this case, the Supreme Court has failed to bring badly needed transparency to the surveillance court and to rulings that impact millions of Americans. Secret court decisions are corrosive in a democracy, especially when they so often hand the government the power to peer into our digital lives,” said Patrick Toomey, senior staff attorney at the ACLU’s National Security Project. “Our privacy rights rise or fall with the court’s decisions, which increasingly apply outdated laws to the new technologies we rely on every day. These opinions are the law and they should be public, not kept hidden from Americans whose rights hang in the balance.”

Attorney Tali Leinwand, an author of the amicus brief filed in the case on behalf of former magistrate judges, provided an email statement to Law&Crime saying, “We are disappointed that the Supreme Court will not have the opportunity to consider the right of public access to significant FISC opinions given the FISC’s role in shaping fundamental civil liberties in our digital age.” Leinwand remarked that “magistrate judges across the country have shown for decades that judges are well-equipped to publish significant opinions on novel law enforcement technology without sacrificing the integrity of government investigations,” and argued that “The FISC is well-positioned to do the same.”

Although Justices Gorsuch and Sotomayor are often on opposite sides of SCOTUS votes, Monday’s dissenting statement appears to underscore an alignment seen in early October in another case about intelligence secrecy. During oral arguments in a case about whether the federal government must disclose information about secret overseas CIA prisons known as “black sites,” the two justices tag-teamed the federal government’s lawyer, demanding a “straight answer” as to whether the government would allow a suspected al-Qaeda operative to testify about his imprisonment at Guantanamo Bay.

[Image from ERIN SCHAFF/POOL/AFP via Getty Images]

Editor’s Note: This piece has been updated from its original version to include additional comments from counsel.