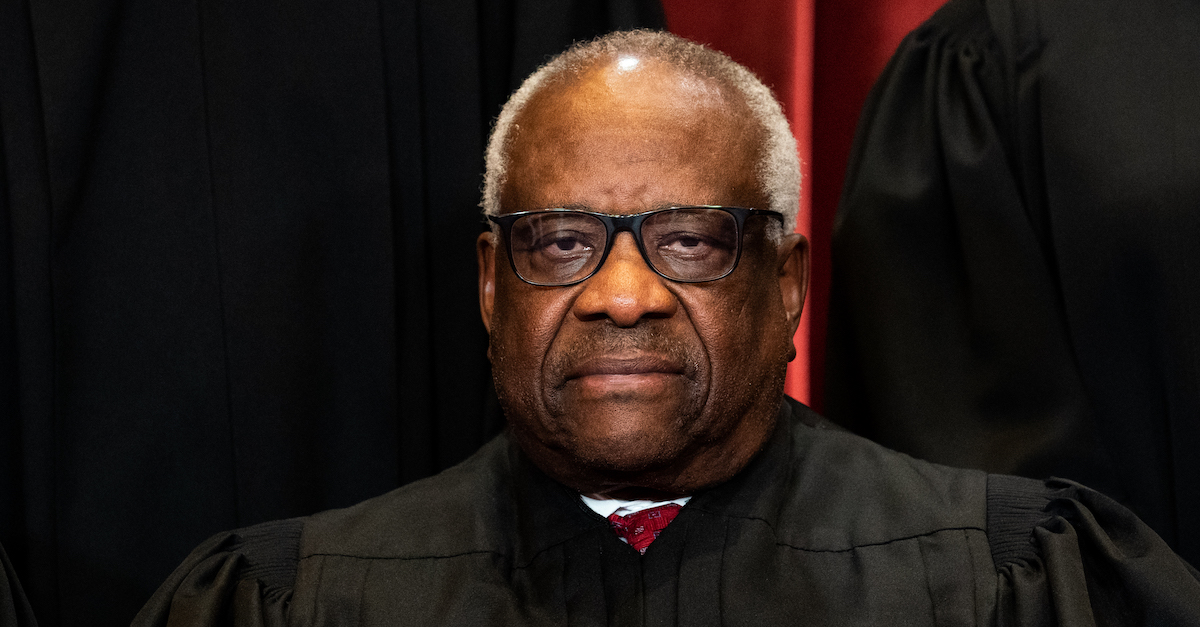

Associate Justice Clarence Thomas

Justice Clarence Thomas spoke out about the wrongheadedness of a Supreme Court ruling that denies a serviceman’s widow the right to sue the United States military for exposing her late husband to toxic drinking water while stationed as an officer.

Thomas penned a 4-page dissent to the Court’s denial of certiorari in Clendening v. United States, in which he urged the high court (as he has done several times in the past) to overrule the so-called “Feres doctrine.” The doctrine is named for the unanimous 1950 SCOTUS ruling in Feres v. United States, which protects the federal government from defending a wide range of tort lawsuits that otherwise might be waged by members of the military.

Carol Clendening sought to recover for her husband Gary’s exposure to contaminated drinking water while serving as a judge advocate general officer at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina. Gary Clendening was diagnosed with leukemia in 2007 and died in 2016. Both the district court and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit found that Clendening’s lawsuit was barred by Feres v. United States, which held that service members cannot sue the federal government for any injury “incident to military service.”

Although the federal government is immune from most torts lawsuits filed by individuals, the Federal Tort Claims Act (FTCA) wavies that sovereign immunity in most cases like Clendening’s. Therefore, for a great number of military plaintiffs, the Feres doctrine is the insurmountable legal hurdle that prevents their recovery.

In his dissent from the Supreme Court’s refusal to hear Clendening’s case, Thomas argued that judiciary’s “attempts to apply [the Feres doctrine] are marked by incoherence.” Specifically, Thomas pointed to lower court rulings on the issue of which injuries are “incident to military service” (and therefore, not actionable), versus those that are not (and could form the basis of a civil lawsuit).

Thomas provided some examples for the troublingly inconsistent outcomes in tort cases filed by servicemembers:

One might be surprised to learn, for example, that a serviceman’s exposure to excessive carbon monoxide at Fort Benning is not incident to service, Elliott v. United States, 13 F. 3d 1555, 1556–1557 (CA11 1994), but exposure to contaminated drinking water at Camp Lejeune is, Gros v. United States, 232 Fed. App. 417, 418–419 (CA5 2007) (per curiam). Or that the dissemination of personal materials stored on a military base by fellow servicemen is notincident to service, Lutz v. Secretary of the Air Force, 944 F. 2d 1477, 1478–1479 (CA9 1991), but a West Point cadet’s rape by a fellow cadet is, Doe v. Hagenbeck. [emphasis Thomas’]

Thomas dismissed Feres’ “professed concern with military discipline” as “anomalous, if not downright hypocritical” when set against the backdrop of general military law. Servicemembers can and do bring lawsuits to redress wrongs suffered during the course of their military service, explained Thomas — and precluding tort claims like Clendening’s poses no greater threat to military discipline.

“Apparently, the Court cares about the chain of command when considering money-damages suits against the Government, but our concerns evaporate when servicemen seek injunctions against their superior officers’ personnel decisions,” Thomas wrote.

Thomas ended his dissent by reminding the Supreme Court that the Feres doctrine was judicially created and, therefore, should be judicially remedied:

It would be one thing if Congress itself were responsible for this incoherence. But Congress set out a comprehensive scheme waiving sovereign immunity that we have disregarded in the military context for nearly 75 years. Because we caused this chaos, it is our job to fix it.

The conservative justice, as well as the late Justice Antonin Scalia have both advocated for overruling Feres. So has the ACLU.

[Image via Erin Schaff/Pool/Getty Images]