Justice Clarence Thomas was the sole member of the Supreme Court to speak out Monday, criticizing the Court’s refusal to hear the case of a West Point cadet who said she was raped by a fellow cadet. Thomas’ dissent from the Court’s order was a rare moment where the conservative justice sided with the ACLU, but it was also a chance for Thomas to remind the Court that there are certain precedents he’d be fine with abandoning altogether.

The case at hand, Jane Doe v. United States, is an appeal from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit over whether a service member is entitled to bring suit against the government. Under the prevailing case law, military personnel are prohibited from suing the federal government because the United States has sovereign immunity under the Federal Tort Claims Act (“FTCA”).

Doe’s case provides SCOTUS with an opportunity to overrule the 1950 case that foreclosed lawsuits like Doe’s against the military. Feres v. United States was a unanimous decision that created the widely criticized “Feres Doctrine,” which protects the government from defending a wide range of tort lawsuits that otherwise might be waged by members of the military.

Doe filed a petition for certiorari, arguing that SCOTUS should take up her case, overrule Feres, and side with survivors of sexual violence at military academies. From Doe’s petition:

West Point and its leaders fostered a sexually aggressive and misogynistic environment, failed to punish rapists and other sexual assailants, and failed to implement mandatory DOD directives and instructions to protect victims. Ms. Doe suffered the full consequences of West Point’s blatant disregard of DOD policies on May 8, 2010, when she was raped by a fellow cadet. Ms. Doe was attacked in an academic building, after-hours, during the course of a recreational nighttime walk. She sought immediate medical care from West Point, which once again failed to comply with mandatory military directives or to provide appropriate medical and emotional support. Three months later, she resigned and left the school. Ms. Doe’s departure was a bitter loss to a young woman who had dreamed of serving her country. It was also a tragic loss to the nation of a promising future soldier.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and multiple other organizations filed amicus briefs, supporting Doe’s case and arguing that it’s time for the Feres doctrine to go.

Without comment from the Court’s majority, the Supreme Court declined to hear Doe’s case. As is the usual practice in a denial of certiorari, the Court did not release information indicating the breakdown of votes. Justice Thomas, however, penned a three-page dissent from the Court’s order.

Thomas argued that Doe should have been allowed to bring her case against the federal government, calling attention to the illogic of a rule that allows government contractors to sue for tort when government employees cannot. Although Congress had not specifically prohibited lawsuits like Doe’s in the FTCA, “70 years ago, this Court made the policy judgment that members of the military should not be able to sue for injuries incident to military service,” pointed out the justice.

Calling a prohibition against lawsuits by military members an approach supported by “little justification,” Thomas bluntly wrote, “Feres was wrongly decided; and this case was wrongly decided as a result.”

In a pragmatic style of writing, Thomas provided multiple examples of how the Feres doctrine creates unfair results. “Under our precedent,” he explained, “if two Pentagon employees— one civilian and one a servicemember—are hit by a bus in the Pentagon parking lot and sue, it may be that only the civilian would have a chance to litigate his claim.” Thomas went on, saying the Feres doctrine is not only a bad rule, but also tends to be applied inconsistently.

“Feres apparently forecloses a claim for a servicemember’s injury while waterskiing because the recreational boat belonged to the military, but not for an injury while attending a rugby event caused by a servicemember’s negligent operation of an Army van,” Thomas wrote.

Justice Thomas also had words for a Court that he suggested is more concerned with stare decisis than it should be. Criticizing a bench that may have chosen to avoid Doe’s case, “because it would require fiddling with a 70-year-old precedent that is demonstrably wrong,” Thomas schooled his colleagues, “But if the Feres doctrine is so wrong that we cannot figure out how to rein it in, then the better answer is to bid it farewell.” Remarking that “there is precedent” for throwing out a wrong-footed precedent, Thomas listed numerous cases in which the Court has done just that, including Korematsu v. United States, Brown v. Board of Education, and Erie R. Co. v. Tompkins.

He urged the court to follow that approach.

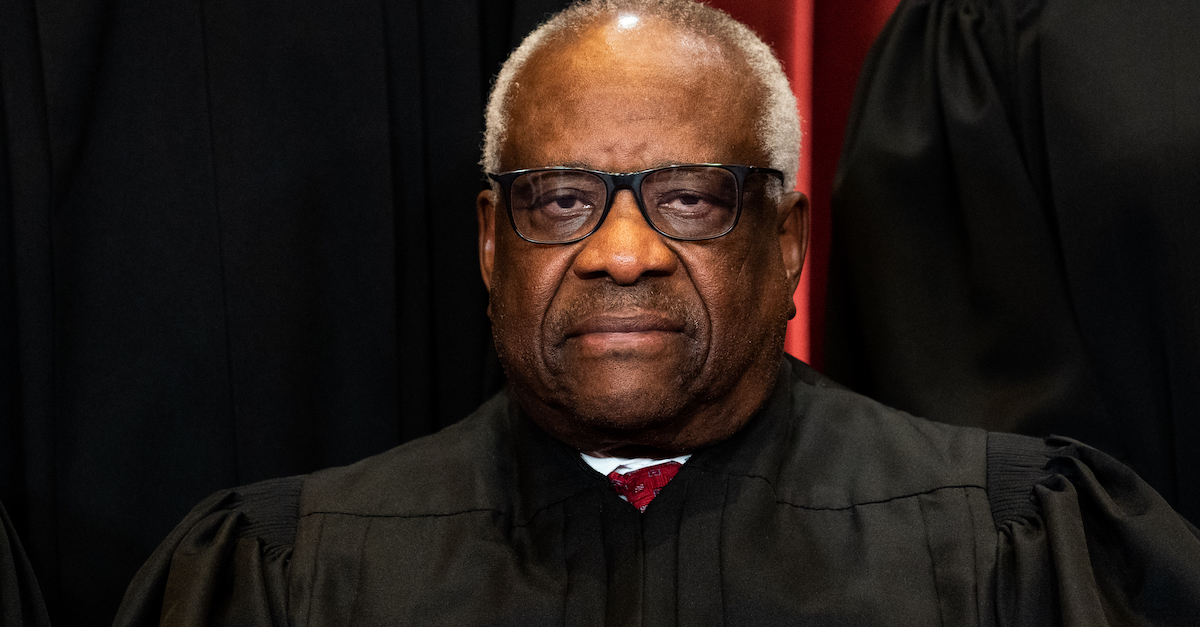

[Image via Erin Schaff-Pool/Getty Images]