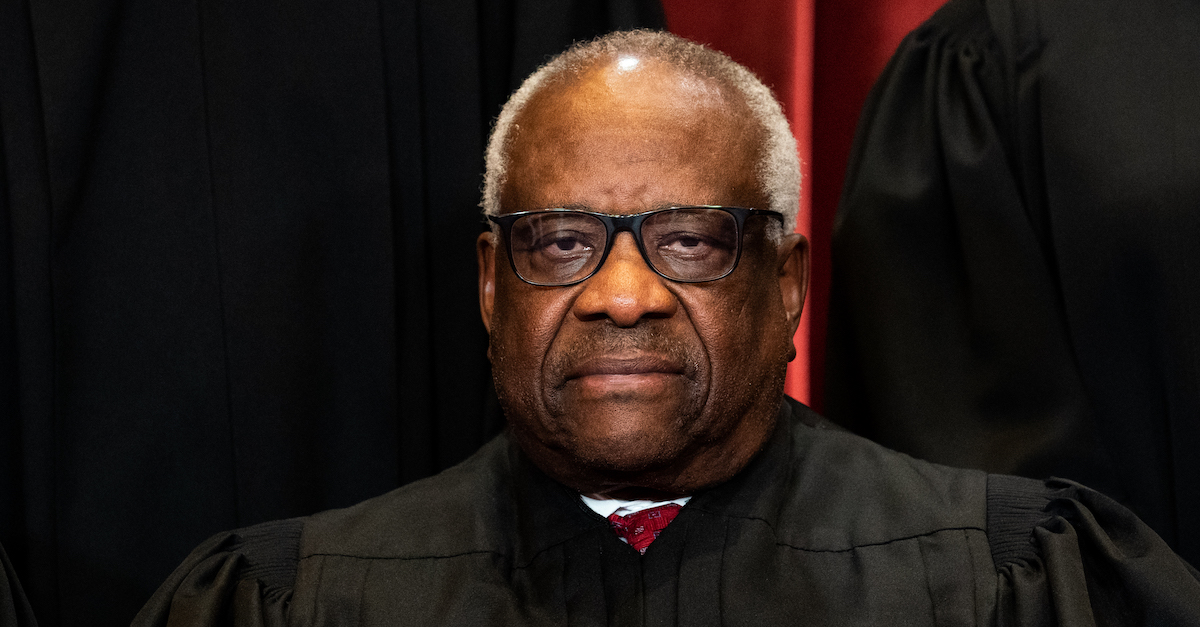

Associate Justice Clarence Thomas sits during a group photo of the Justices at the Supreme Court in Washington, D.C on April 23, 2021. (Photo by Erin Schaff/Pool/Getty Images.)

Justices Clarence Thomas and Brett Kavanaugh filed concurring opinions, and Chief Justice John Roberts “filed an opinion concurring in the judgment,” in connection with the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision to overrule Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey on Friday. The majority’s opinion returns the question of abortion to the states — meaning some states can criminalize the procedure while others can allow it. The majority opinion holds that there is no right to abortion under the U.S. Constitution.

This report addresses Thomas’s concurrence; Law&Crime has addressed the majority opinion in a separate report.

Justice Thomas welcomed arguments to eliminate other currently recognized constitutional rights, such as the rights to contraception, private sexual acts (including homosexuality), and same-sex marriage. He also compared the number of aborted fetuses with the number of soldiers killed fighting the Civil War in an analogy which sought to caution jurists that constitutional interpretative methods cost lives.

“I join the opinion of the Court because it correctly holds that there is no constitutional right to abortion,” Justice Thomas wrote in a seven-page concurring opinion (pages 117 to 123 of the full 213-page document).

Thomas spent a brief paragraph recapping the rationale behind the majority opinion: that the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment (that no state shall “deprive any person of life, liberty, or property without due process of law”) does not protect abortion, contrary to the now-scuttled holdings of Roe and Casey. That is because, per the Court as of Friday, abortion is not “deeply rooted in this Nation’s history and tradition” nor “implicit in the concept of ordered liberty.”

Overall, Thomas argued for a split from the Court’s generally long-held belief that the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment provided a wellspring of certain “fundamental” rights that were embedded within and extrapolated from some words and phrases in the Constitution — especially from the word “liberty.” Those rights, which have been liberally interpreted in past cases like Roe and Casey, are increasingly being perceived by the Court as separate from the Constitution’s enumerated rights: free speech, religious exercise, gun rights, and the like.

There’s a legal term for one area of recognition for such rights: “substantive due process.” Thomas wrote that “substantive due process” was “an oxymoron that lacks any basis in the Constitution.” (Another source of “fundamental rights” is the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.)

“The resolution of this case is thus straightforward,” Thomas continued. “Because the Due Process Clause does not secure any substantive rights, it does not secure a right to abortion.”

“Considerable historical evidence indicates that ‘due process of law’ merely required executive and judicial actors to comply with legislative enactments and the common law when depriving a person of life, liberty, or property,” Thomas said elsewhere. “Other sources, by contrast, suggest that ‘due process of law’ prohibited legislatures from authorizing the deprivation of a person’s life, liberty, or property without providing him the customary procedures to which freemen were entitled by the old law of England.”

“Either way, the Due Process Clause at most guarantees process,” Thomas continued. “It does not, as the Court’s substantive due process cases suppose, forbid the government to infringe certain ‘fundamental’ liberty interests at all, no matter what process is provided.”

Thomas argued for a split between the concepts of “substantive due process” (which he bemoaned as a stretch too far) and what’s known as “procedural due process” (the “process” he mentioned above). And he was unabashed at how far he was willing to drive that wedge. Though the Court was not asked in the instant case — Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization — to overturn similar “substantive due process” rights, Thomas said those rights were, indeed, in his opinion, on the chopping block. The specific rights he named were the right to contraception, the right to engage in private homosexual acts, and the right to same-sex marriage.

“The Court’s abortion cases are unique,” Thomas wrote, and “nothing in the Court’s opinion should be understood to cast doubt on precedents that do not concern abortion.”

But, he signaled that he was potentially willing to chop away nonetheless: “in future cases, we should reconsider all of this Court’s substantive due process precedents, including Griswold [contraception], Lawrence [sexual acts], and Obergefell [same-sex marriage].”

“Because any substantive due process decision is demonstrably erroneous, we have a duty to ‘correct the error’ established in those precedents,” Thomas continued.

But those rights might — perhaps — be found elsewhere, he suggested. Or maybe not:

After overruling these demonstrably erroneous decisions, the question would remain whether other constitutional provisions guarantee the myriad rights that our substantive due process cases have generated. For example, we could consider whether any of the rights announced in this Court’s substantive due process cases are “privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States” protected by the Fourteenth Amendment. To answer that question, we would need to decide important antecedent questions, including whether the Privileges or Immunities Clause protects any rights that are not enumerated in the Constitution and, if so, how to identify those rights. That said, even if the Clause does protect unenumerated rights, the Court conclusively demonstrates that abortion is not one of them under any plausible interpretive approach.

In a footnote, Thomas lambasted the “facial absurdity” of the Griswold holding.

Returning to the issue of abortion, Thomas said the entire concept of “substantive due process” simply “exalts judges at the expense of the People from whom they derive their authority.”

Or, in other words, the individual cannot make decisions apart from big government — elected by “the People.” Thomas penned several paragraphs toward this end; he skewered the notion that abortion was a “privacy” interest held by the individual apart from government regulation.

A few lines then knocked the pro-choice parties who pressed the case: Respondents and the United States propose no fewer than three different interests that supposedly spring from the Due Process Clause. They include “bodily integrity,” “personal autonomy in matters of family, medical care, and faith,” Brief for Respondents 21, and “women’s equal citizenship,” Brief for United States as Amicus Curiae 24. That 50 years have passed since Roe and abortion advocates still cannot coherently articulate the right (or rights) at stake proves the obvious: The right to abortion is ultimately a policy goal in desperate search of a constitutional justification.

Another case which exhibited a “a species of substantive due process,” according to Thomas, was the Dred Scott decision — the pre-Civil War case that held 7-2 that a Black man descended from slaves was not a citizen had no standing to sue for his freedom. Thomas laid out the logic by quoting old cases and ended with a comparison between Civil War deaths and the number abortions performed in the United States:

While Dred Scott “was overruled on the battlefields of the Civil War and by constitutional amendment after Appomattox,” that overruling was “[p]urchased at the price of immeasurable human suffering.” Now today, the Court rightly overrules Roe and Casey — two of this Court’s “most notoriously incorrect” substantive due process decisions, after more than 63 million abortions have been performed. The harm caused by this Court’s forays into substantive due process remains immeasurable.

Thomas concluded:

Because the Court properly applies our substantive due process precedents to reject the fabrication of a constitutional right to abortion, and because this case does not present the opportunity to reject substantive due process entirely, I join the Court’s opinion. But, in future cases, we should “follow the text of the Constitution, which sets forth certain substantive rights that cannot be taken away, and adds, beyond that, a right to due process when life, liberty, or property is to be taken away.” Carlton, 512 U. S., at 42 (opinion of Scalia, J.). Substantive due process conflicts with that textual command and has harmed our country in many ways. Accordingly, we should eliminate it from our jurisprudence at the earliest opportunity.

The full Thomas concurrence is below:

Editor’s note: internal punctuation marks and legal citations have been omitted from many quotes in this piece for ease of readability.