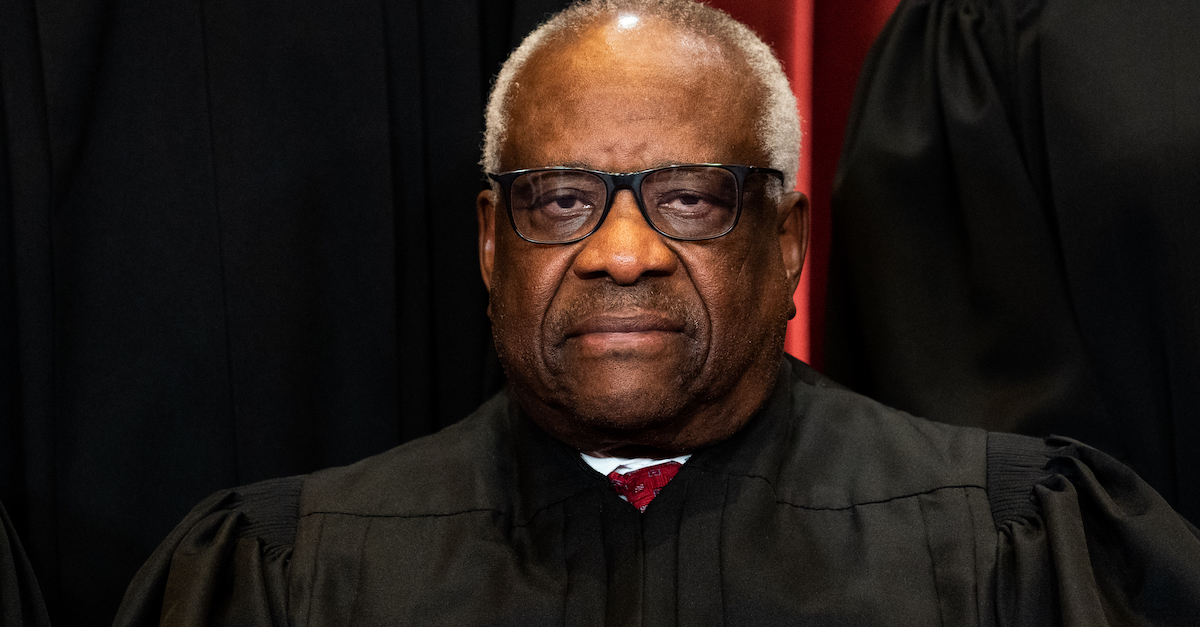

Associate Justice Clarence Thomas

The Supreme Court of the United States on Tuesday decided not to hear a petition by the State of Ohio, which sought to overturn habeas corpus relief granted to a convicted murderer who was sentenced to die after a trial court refused to allow him to serve as his own lawyer.

In Shoop v. Cassano, the justices denied Ohio’s request, which means the ruling in favor of the inmate will remain in place for now. Justice Clarence Thomas wrote a lengthy dissent from the denial of certiorari, however, arguing that the case should have been taken up and the lower court’s ruling summarily reversed.

Justice Thomas began his dissent with a recap of the grisly facts underlying the case, writing that August Cassano is “no stranger to violence.” Cassano and an accomplice shot bartender Donald Pinto “through the heart during a heist in Akron, Ohio.” Thomas added some unrelated background facts to paint a more complete picture of Cassano’s time as an inmate: “Over his first 21 years in custody, Cassano participated in over 100 fights and stabbed four people. Once, he stabbed a fellow inmate approximately 32 times before the victim escaped.”

During his time in prison, Cassano was assigned a new cellmate named Walter Hardy.

“That decision angered Cassano, who said he ‘didn’t want that snitching ass faggot in his cell,'” Thomas continued.

When Hardy was not removed from the cell days later, Cassano stabbed Hardy to death “75 times with a prison shank.” An Ohio jury convicted Cassano of capital murder and sentenced him to death for that killing.

Now — and as Thomas pointed out, a quarter of a century later — Cassano fights to uphold a favorable ruling on habeas corpus relief. The petition before SCOTUS did not concern the facts of the underlying murder. Rather, it focused on post-conviction relief granted on the basis of Cassano’s problems with legal representation at trial.

Cassano made some conflicting statements to the trial court about who he wanted to represent him. Before Cassano’s trial for murdering Hardy, Cassano filed a “waiver of counsel” at the same time he filed a request for appointed counsel. Three days before the trial began, Cassano told the court that he thought his lead attorney was unprepared, and asked “is there any possibility I could represent myself?” He added, “I’d like that to go on record.”

Cassano filed a motion requesting to participate in the trial as co-counsel along with lawyers, but the trial court denied the motion. In another motion filed on the same day (described by Justice Thomas a “dueling request”), Cassano requested substitute counsel. The trial judge refused Cassano’s request, and Cassano was convicted and sentenced to death.

Cassano appealed and argued that he was denied his right to self-representation. After Cassano’s appeals failed in state court, he brought a claim for federal habeas corpus relief in federal court. The district court sided against Cassano, but a panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit reversed in a 2-1 ruling. The Sixth Circuit majority found that Cassano’s request had been clear and unequivocal, and conditionally granted habeas relief on that basis unless Ohio retried Cassano within six months.

Thomas called the case “straightforward” under the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996 (AEDPA). The justice repeated his usual refrain: that federal courts should seriously hesitate before second-guessing state convictions.

“Here, it is obvious that the Supreme Court of Ohio did not ‘inadvertently overloo[k]'” Cassano’s potential claim, Thomas said. Rather, the circumstances underlying Cassano’s appeals had been problematic. Thomas explained:

To start, Cassano filed his May 1998 motion for waiver of counsel simultaneously with his request for substitute counsel. (They were docketed within a minute of one another.) Neither motion referenced the other. Given these simultaneous, contradictory motions, a fairminded jurist could easily agree with the Supreme Court of Ohio that Cassano did not clearly and unequivocally invoke his right to represent himself. In fact, two federal jurists would have held that Cassano made no clear and unequivocal demand to represent himself…

Thomas said Cassano’s inquiry about representing himself was merely a “tepid question” and not a demand, and that it was unclear whether Cassano actually wanted counsel. The trial court, said Thomas, did not neglect or forget about Cassano’s request. Rather, he said, it found that Cassano’s contradictory statements simply did not add up to a valid request for self-representation.

Thomas reasoned that given the fact that fair-minded jurists could reasonably disagree as to Cassano’s wishes regarding counsel, the Sixth Circuit’s decision “was obviously wrong” in that it was not deferential enough to state rulings as is required by AEDPA. Thomas had a further reprimand for the Sixth Circuit.

“Over the last two decades, we have reversed the Sixth Circuit almost two dozen times for failing to apply AEDPA properly,” Thomas wrote, lamenting that SCOTUS “chooses to leave in place a clearly erroneous decision that relieves Cassano of his death sentence.”

“In doing so,” the justice continued, “the Court inflicts a harm on ‘the State and its citizens.'”

[Image via Erin Schaff-Pool/Getty Images]