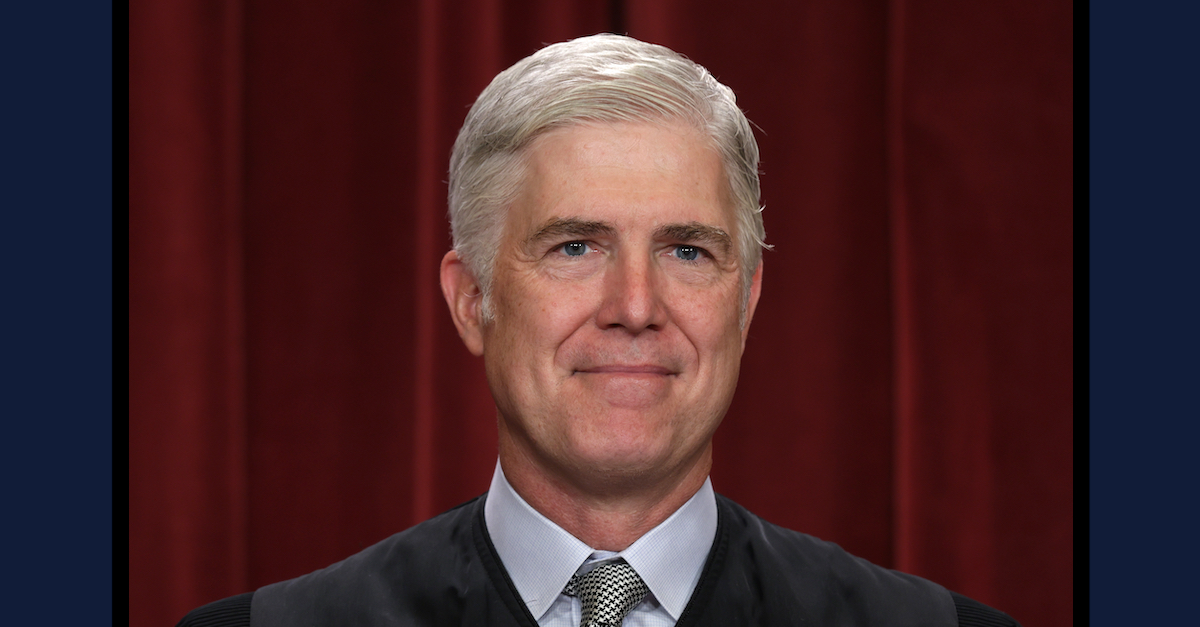

Justice Neil Gorsuch poses for an official portrait in the East Conference Room of the Supreme Court building on October 7, 2022 in Washington, D.C. (Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images.)

The justices heard oral arguments Wednesday in a case involving a narrow issue of potentially massive importance: whether a person who violates the Bank Secrecy Act by failing to disclose foreign bank accounts commits separate offenses for each account or one offense for the overall failure to report. The case is Bittner v. United States, an appeal from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit.

For Alexandru Bittner, the difference at stake is profound. One interpretation of the statute will result in his being fined $50,000 while the other will mean a $2.72 million penalty. If Bittner had been accused of intentionally violating the statute, the difference would have been $1.25 million versus $68 million in fines and 25 versus 1,360 years in prison. An intentional violation would have triggered a criminal penalty; here, the proposed penalty is civil in nature — even though the government is seeking to collect it.

The statute’s requirements are short and simple: any U.S. citizen or resident must keep records and file reports documenting transactions with foreign financial agencies. The records must include information about the parties to and details of these transactions, and they must clarify the identity of the true parties in interest if a transaction is conducted through representatives. The law requires the filing of an annual Report of Foreign Bank and Financial Accounts (FBAR) by any person having “foreign financial accounts exceeding $10,000 maintained during the previous calendar year.”

Bittner was a dual citizen of both Romania and the U.S. who moved back to Romania in 1990. He was a successful businessman in Romania who maintained hundreds of foreign accounts for his $70+ million in income. Because Bittner was still a U.S. citizen, he was still obligated to file FBARs about these accounts. He did file, though he did so after the filing deadline, which triggered $2.7 million in non-willful penalties (the IRS fined him $10,000 per bank account, as opposed to per FBAR).

Bittner argues that the grammar and syntax of the Bank Secrecy Act favors an interpretation that a “violation” is an individual’s failure to file each required report.

Per Bittner’s brief to the Court:

This again comports with ordinary experience and common sense. If a statute says to list all your seven accounts on a single form, no one normally thinks you complied with the law five times and violated it twice if you only list four of six accounts. The natural response is you violated the law once—by not listing all seven accounts as directed. Contrary to the government’s contention, the statutory “require[ment]” is to file the required report (“keep records, file reports, or keep records and file reports”), whatever those reports entail.

By contrast, the federal government characterizes Bittner as someone who tried to “intentionally conceal the reporting of income, assets, or foreign activities” over the period of multiple years. It argues that the relevant statute consistently uses “violation” in reference to each account, as opposed to each filing.

As the justices questioned attorneys on both sides in the matter, they appeared especially skeptical of Bittner’s argument despite the hefty penalties that might result for the businessman.

Justice Elena Kagan began by pressing Bittner’s attorney, Daniel Geyser, on the potential unfairness that could result by adopting his suggested interpretation.

“One might say that your version forces the government to treat equally someone who has a $10,000 account and somebody like your client, who has extreme wealth and many many accounts and where he is depriving the government of much more information,” Kagan told Geyser.

Geyser responded that whether the individual has a large or small number of accounts, the relevant conduct — not filing a report — is the same. Perhaps said another way, the crime, according to Geyer, is not being rich: it’s not filing.

Later, in response to Justice Samuel Alito’s questions along the same lines, Geyser noted for the Court that requiring over 1300 years in prison for failure to file a report seems like a disproportionate penalty.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor also seemed hesitant to adopt Geyser’s interpretation.

“You seem to be equating ‘report’ with ‘a form,’ and I’m equating a ‘report’ with what the statute [says] — ‘an account,'” Sotomayor commented.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh brought background context to the colloquy and reminded Geyser that the law was adopted in the immediate aftermath of the September 11th terrorist attacks.

“Not surprisingly, the statute has substantial penalties and puts the duty on people to know their legal obligations,” said Kavanaugh.

Assistant to the Solicitor General Matthew Guarnieri took the podium on behalf of the federal government and faced a hypothetical from Justice Samuel Alito.

“Suppose someone reports multiple accounts, but messes up the address for each account. How many violations?” asked Alito

Guarnieri answered that ten address errors would amount to ten violations, but added that an innocent error would likely trigger an effective “reasonable cause” defense by the individual.

Later, Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson followed up on the practicalities of relying on affirmative defenses and reminded Guarnieri that the raising of a defense would likely require the individual to hire a lawyer.

Justice Neil Gorsuch turned the conversation in an entirely different (though predictable, for those familiar with Gorsuch’s jurisprudence) direction. As Gorsuch has often done during oral arguments, the justice brought up “Chevron deference” — the administrative law principle by which federal courts defer to a federal agency’s interpretation of an ambiguous statute within that agency’s subject area. Gorsuch, famously hostile to the concept of the doctrine, asked Guarnieri why the government did not even attempt an argument based on Chevron deference.

“It’s garlic to a vampire for the government,” commented Gorsuch on the DOJ’s failure to raise the topic in its argument.

While many court-watchers consider Gorsuch as something of a poster-justice for nixing Chevron deference, he is by no means alone in his distaste for the concept. Rather, the Court’s conservative majority is often broadly critical of federal administrative agencies and any attempt to broaden their power.

You can listen to the full oral arguments, which began with an unexplained disruption in the courtroom as a person yelled something about abortion rights, here.

[image via Alex Wong/Getty Images]