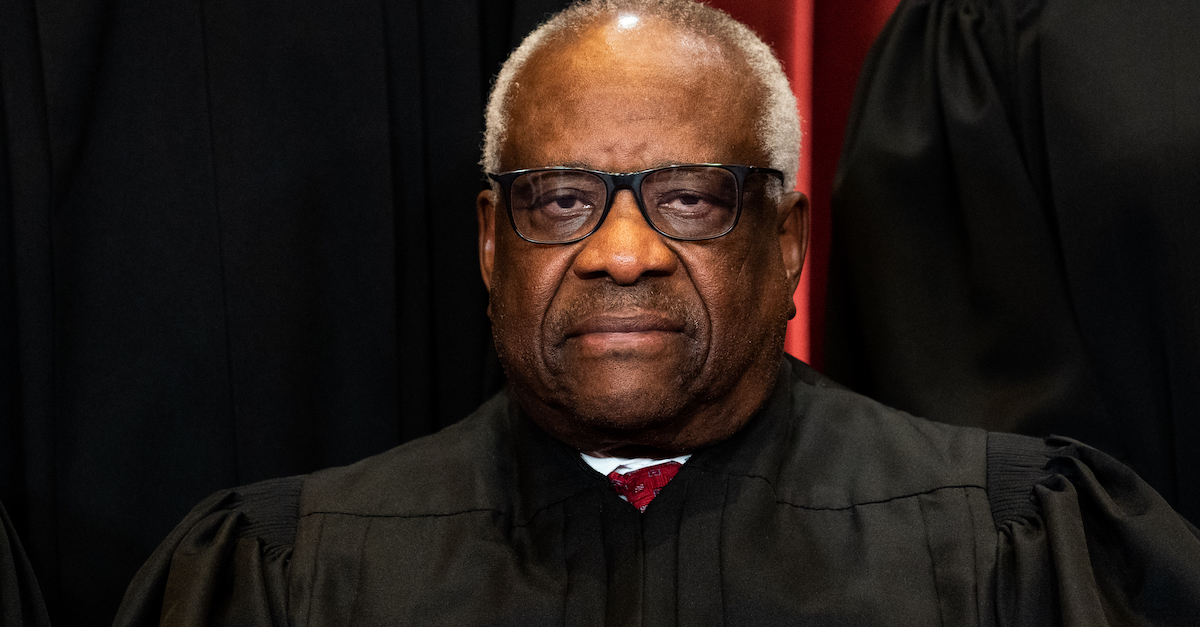

Associate Justice Clarence Thomas sits during a group photo of the Justices at the Supreme Court in Washington, DC on April 23, 2021.

Conservative Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas cast himself as the odd man out on Friday in a much-anticipated ruling on the restrictive, private lawsuit-based anti-abortion regime in Texas.

The majority, in fairly determinative 8-1 fashion, issued its ruling in favor of abortion providers seeking to sue certain state officials. But the victory was limited. Women’s health organizations also sought the ability to sue state court clerks. That second request was denied 5-4 by the emboldened conservatives on the nation’s high court.

Thomas, however, often considered one or two of the most conservative out of the nine justices on the bench, would have dismissed the pro-abortion access plaintiffs’ case altogether.

“In my view, petitioners may not maintain suit against any of the governmental respondents,” Thomas wrote in his procedurally-heavy 8-page dissent. “I would reverse in full the District Court’s denial of respondents’ motions to dismiss and remand with instructions to dismiss the case for lack of subject-matter jurisdiction.”

The core of the dissent is based on the 1908 Supreme Court case stylized as Ex Parte Young, which provides the ability for people to sue state-based actors in their individual capacities–by alleging a constitutional violation–despite the state’s typical court-constructed protection of sovereign immunity. The holding in Young is essentially premised on the idea that a state actor attempting to enforce an unconstitutional law is not really acting on behalf of the state.

To hear Justice Thomas tell it, the Texas anti-abortion law in question, S.B. 8, simply lacks any potential governmental defendants whatsoever.

Or, at least, that’s what the law says.

The justice notes [emphasis in original]:

The only “act alleged to be unconstitutional” here is S.B. 8. And that statute explicitly denies enforcement authority to any governmental official. On this point, the Act is at least triply clear. The statute begins: “Notwithstanding . . . any other law, the requirements of this subchapter shall be enforced exclusively through . . . private civil actions.” Tex. Health & Safety Code Ann. §171.207(a) The Act continues: “No enforcement of this subchapter . . . in response to violations of this subchapter, may be taken or threatened by this state . . . or an executive or administrative officer or employee of this state.” Later on, S. B. 8 reiterates: “Any person, other than an officer or employee of a state or local governmental entity in this state, may bring a civil action.” In short, the Act repeatedly confirms that respondent licensing officials, like any other governmental officials, “hav[e] no duty at all with regard to the act,” and therefore cannot “be properly made parties to the suit.”

But those words in the statute only attempt to disclaim any and state affiliation with enforcing S.B. 8 where, in reality, such a relationship actually does exist, Justice Neil Gorsuch notes in the majority opinion.

The majority cites a provision of “Texas statutory law that includes S.B. 8” which says the Texas Medical Board must “take an appropriate disciplinary action against a physician who violates” the law.

“Accordingly, it appears Texas law imposes on the licensing-official defendants a duty to enforce a law that ‘regulate[s] or prohibit[s] abortion,’ a duty expressly preserved by S. B. 8’s saving clause,” Gorsuch notes. “Of course, Texas courts and not this one are the final arbiters of the meaning of state statutory directions. But at least based on the limited arguments put to us at this stage of the litigation, it appears that the licensing defendants do have authority to enforce S. B. 8.”

Thomas concedes for the sake of argument that even if there is someone for the abortion providers to sue, they don’t actually have a real, particularized legal grievance because no action had been taken against anyone at the time the raft of lawsuits were filed.

“Rather, petitioners complain of the ‘chill’ S. B. 8 has on the purported right to abortion,” Thomas argues. “But as our cases make clear, it is not enough that petitioners ‘feel inhibited’ because S. B. 8 is ‘on the books.’ Nor is a ‘vague allegation’ of potential enforcement permissible. To sustain suit against the licensing officials, whether under Article III or Ex parte Young, petitioners must show at least a credible and specific threat of enforcement to rescind their medical licenses or assess some other penalty under S. B. 8.”

The majority batted away those concerns by noting the women’s healthcare providers have “plausibly alleged that S. B. 8 has already had a direct effect on their day-to-day operations” and again referenced the ancillary licensing provisions that serve as an actual method of state enforcement–despite what the law claims to say.

Thomas also argues that the plaintiffs lack standing. This argument is mostly dispensed with in a lengthy footnote where he says, citing himself, that “abortion providers lack standing to assert the putative constitutional rights of their potential clients.”

“[T]here is no freestanding constitutional right to pre-enforcement review in federal court,” Thomas writes in the body of his dissent. “Such a right would stand in significant tension with the longstanding Article III principle that federal courts generally may not ‘give advisory rulings on the potential success of an affirmative defense before a cause of action has even accrued.'”

[image via Erin Schaff-Pool/Getty Images]