The U.S. Supreme Court heard oral arguments on Monday morning in a case about what sort of public statements made by corporations can qualify as securities fraud subject to class action lawsuits.

Securities law is notoriously elusive and often complex—typically being hashed out via ever-evolving administrative rulemaking and enforcement action scenarios when the government is concerned. Here, however, the facts of the case stylized as Goldman Sachs Group v. Arkansas Teacher Retirement System are fairly simple: shareholders of an asset class claim they were misled by false public statements; when the stock tanked, they sued.

Specifically, between 2006 and 2010, investment bank Goldman Sachs made several glowing statements about its business practices. Many of those statements highlighted their ability to assess and adequately deal with potential conflicts of interest.

Statements at issue include:

“We have extensive procedures and controls that are designed to identify and address conflicts of interest” and “Our reputation is one of our most important assets. As we have expanded the scope of our business and our client base, we increasingly have to address potential conflicts of interest, including situations where our services to a particular client or our own proprietary investments or other interests conflict, or are perceived to conflict, with the interest of another client.”

But Goldman Sachs often made deals that directly undercut their own clients’ position. Goldman Sachs, in effect, bet that many of their clients would fail. During the 2008 financial crisis—and its directly resulting crises over the following two years viz. the subprime mortgage scandal—that’s exactly what happened.

“At times, Goldman allegedly represented to its investors that it was aligned with them when it was in fact short selling against their positions.” the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit explained.

After the truth came out, helped along by a government lawsuit that was settled, the bank’s stock plummeted. In turn, a collection of teachers, other state employees and plumbers, pension funds and individual shareholders of Goldman Sachs stock sued by claiming the bank’s boosterism constituted actionable securities fraud.

Originally filed in 2011, the $13 billion case against the bank has taken numerous alleyways and avenues on its way to the high court. Procedural wrangling—in the form of multiple district court level determinations, appellate remands and reviews—has complicated the legal issues in an already murky area.

Simultaneously, this parry and thrust action between the parties and in various courts over a decade has pared down each side’s legal arguments substantially. Now, before the nation’s high court, the basic facts are more or less uncontested. And, key here, so is their basic statement of the law. This left the nine justices to consider whether or not there’s even much of an issue to even deal with.

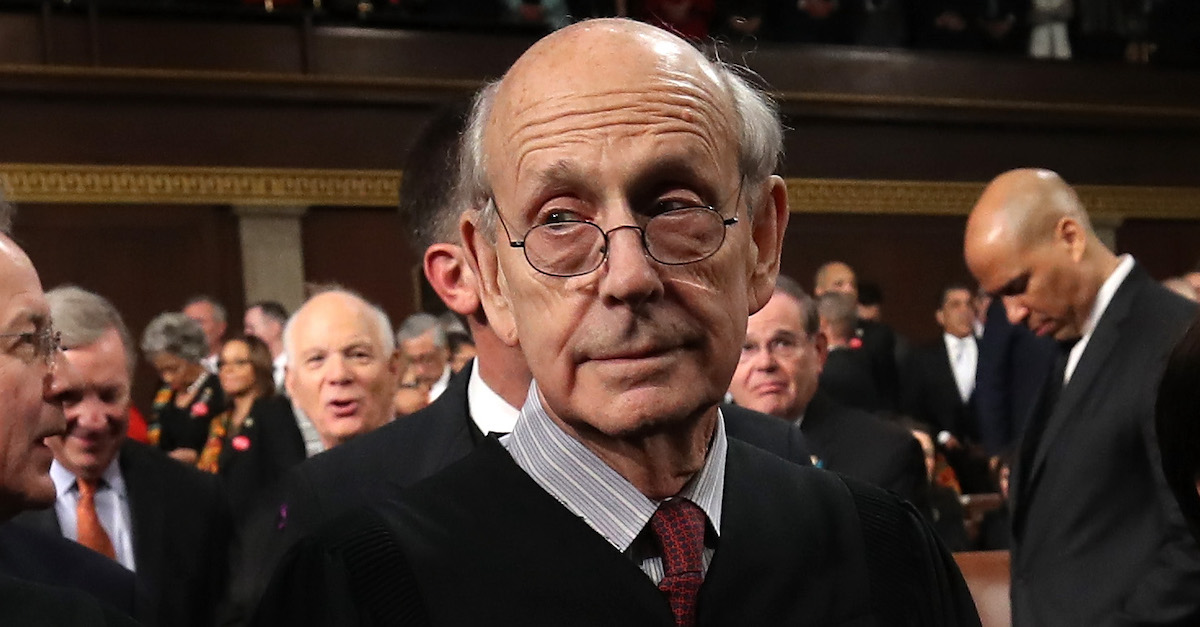

“What’s the legal issue?” Justice Stephen Breyer asked in a representative turn of skepticism about the court’s role in the outstanding dispute. Much was made of the fact, by nearly all of the justices, that the underlying legal framework is essentially agreed to between the teachers and the bank.

That is, both sides have, over the years, moved closer together on the question of whether the generic nature of a company’s statements can be considered important evidence of price impact. Attorney Thomas Goldstein, representing the teachers, said this was true but noted the two sides have only moved so close together because the Second Circuit eventually ruled in the teachers’ favor by crafting the “correct statement of law” in a nuanced manner and the teachers want the Supreme Court to say the appeals court got it right.

Attorney Kannon Shanmugam, representing the bank, argued that the court of appeals’ framework would make it “impossible for a defendant to rebut a plaintiff’s statement” and tacked on the gloom-and-doom of floodgates opening that would result in a torrent of litigation over public statements made by companies because “almost anything could be considered securities fraud.”

But the major dispute legal dispute was framed as a disagreement over when and how a judge should consider expert testimony that relates to a company’s public statements.

“District courts all the time weigh expert testimony with other evidence,” Shunmugam said in response to a question from Justice Sonia Sotomayor over whether a judge’s instinct should prevail over a large group of experts.”The court should take the nature of a statement together with the expert testimony.”

And, on that front, Goldstein and the teachers agreed. So did Assistant U.S. Solicitor General Sopan Joshi—who took neither side but wanted the Supreme Court to clarify the law in this instance.

During the government’s presentation, Justice Breyer wondered whether the nonsense word “ishkabibble” could have an impact on price if a company’s executive started saying it during a press conference even though it is “clearly not material.” That remained an open question.

“On the substance of the first question there is no difference between the parties and the United States,” Goldstein said. “We do believe that that ought to be addressed and principally by expert testimony and that judges can evaluate that testimony on the basis of common sense.”

Justice Elena Kagan later said she was “suspicious” as to exactly how close both sides were on the genericness standard and the application of a judge’s common sense. Goldstein then explained that he simply thinks judges should be able to evaluate expert testimony—which is what happened in the case at bar.

“The judge is not required to turn himself or herself into a computer,” the teacher’s attorney said, “But a judge shouldn’t just say they know how economic markets work.”

But all roads lead back to genericness. And, again, here the parties were both basically on the same page.

“The more generic a statement it is, the less likely it is to have price impact,” Shanmugam explained to Justice Samuel Alito. The bank’s attorney later defined “generic” as “little specific factual content” in response to a question from Justice Brett Kavanaugh about adjectives.

“Do you agree that the generic nature of a statement is important evidence of a price impact?” Kavanaugh asked the teachers’ attorney. Yes, Goldstein replied, depending on the context.

Pressed to account for the actual difference between the parties here, Shanmugam later argued that the genericness determination should be “a sliding scale” and claimed that the teachers relied on a single expert “who couldn’t attribute the stock drop to the disclosures at issue.”

Goldstein said that characterization “made my head hurt” and went on to note that the teachers’ expert had produced several documents containing expert testimony which accounted for Goldman Sachs’s business model. “There is extensive evidence on our side,” he concluded.

And that was the actual heart of the matter.

Shunmugam said the teachers’ expert testimony was “painfully thin” and therefore shouldn’t have been enough to counter Goldman Sachs’s own expert’s conclusion about the alleged lack of impact that generic statements have on a company’s stock price.

Goldstein argued that Goldman Sach’s statements at issue were “not purely generic.” And he went on to note that the teachers; expert opinions “attributed the drop in the share price to statements made by Goldman about how they resolve conflicts of interest.”

As for where that left the nation’s high court, not even they seemed to really know.

[image via Win McNamee/Getty Images]