The Supreme Court of the United States on Wednesday heard oral arguments in a case about whether a complicated regime of signage regulations in Texas runs afoul of the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

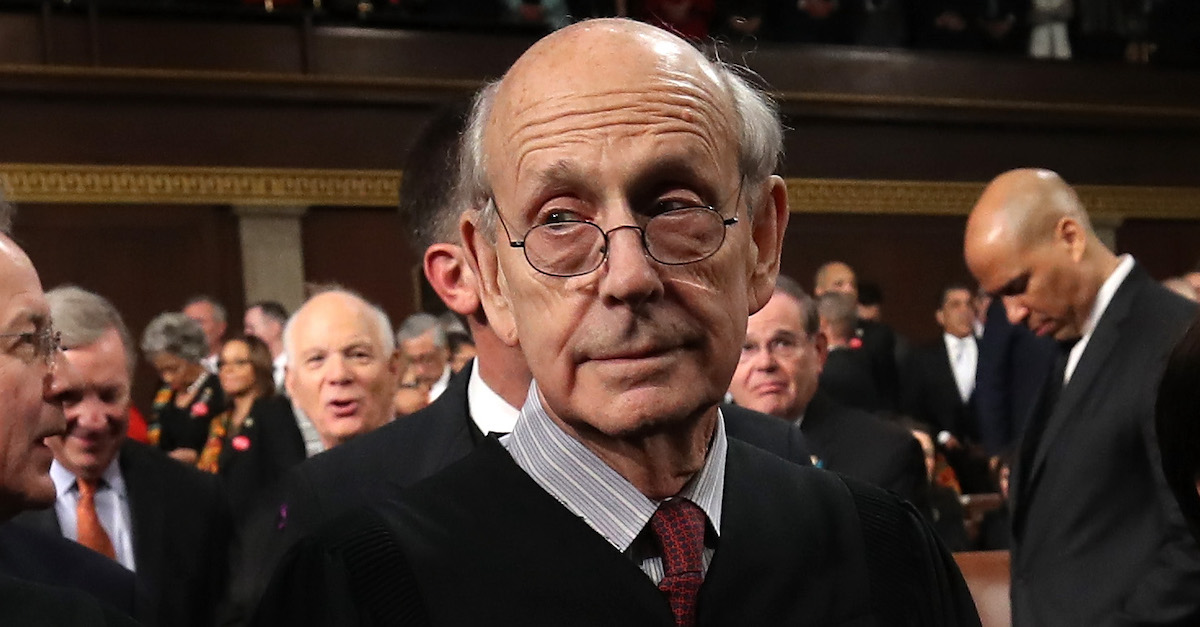

While the full court betrayed very little of the eventual disposition, liberal Justice Stephen Breyer garnered numerous audible laughs during his decidedly skeptical questioning of the sign company attorney challenging the restrictions in the local ordinance at issue.

The laugh lines came when Breyer laid out a hypothetical about a roadside kale shop that he wanted to promote, with signage that would comply with regulations inside the Lone Star State’s capital city.

Stylized as City of Austin v. Reagan National Advertising of Texas, the case concerns a series of digital sign permits which were denied under the liberal city’s efforts to control, what it terms, “problems of esthetic blight and traffic hazards posed by the proliferation of signs.”

Signs, of course, are all over Texas. Any visitor to (or resident of) Dallas, particularly highway users, can understand why Austin would want to tamp down on the abundance of digital billboards, though the law often doesn’t turn or take into account such concerns.

The regulation itself generally allows signs that advertise “on premises” businesses or activities but generally prohibits the construction of new “off premises” signs that don’t have any connection to the location where they would be placed.

Existing, non-digital, on-premises signs can be converted into new digital signs while preexisting off-premises, non-digital signs cannot be converted into new digital signs–which is largely what the sign companies, in their applications and briefs, say they want to do. This disparate treatment, the two major Texas sign companies challenging the restrictions, say is unconstitutional and doesn’t make sense.

The discrete legal issue in the case is whether the digital billboard ban is a facially unconstitutional regulation based on the content of the would-be signs at issue.

A district court in the Lone Star State signed off on the Austin ordinance and was promptly overturned by the solidly conservative U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit. The appellate court ruled in the companies’ favor by citing language contained in the 9-0 Supreme Court ruling from the case stylized as Reed v. Town of Gilbert. In that case, the high court rejected a scheme by an Arizona town that specifically–and more harshly–targeted directional signs related to an event sponsored by any given non-profit group.

The court of appeals, quoting Justice Clarence Thomas from Reed, said because someone would have to “read the sign” to determine whether or not the billboard was related to its location, the regulation was content-based and must fail under a strict scrutiny analysis–an analytical framework which doesn’t have to consider any alleged governmental interest in determining constitutionality.

Breyer, who rejected the court’s analysis in Reed while reaching the same legal conclusion, appeared wholly uninterested in the sign companies’ arguments on Wednesday–subjecting them to withering ridicule and racking up laughter as he told attorney Kannon K. Shanmugam about his general theory of First Amendment jurisprudence.

“I’ll tell you why we let the home [have a digital sign],” Breyer said, taking issue with the argument about unequal, location-based limits on digital signage raised by the companies challenging the law.

“My own kale shop,” Breyer continued, as others slowly laughed louder and louder.

The laughter went unexplained, and seemingly random hypotheticals are a mainstay of Supreme Court argument. Outside the rarefied confines of the courtroom, however, social media unpacked some of the humor. For Anthony Sanders of the Director of the Center for Judicial Engagement, the image itself had comic potential.

Bloomberg’s Supreme Court reporter Greg Stohr found the Breyer hypothetical characteristic of the justice.

“I sell fried kale,” Breyer continued. “And right outside I want a big picture of kale that lights up, okay? It’s mine. This is my shop. I want to decorate it the way I want–a strong interest. I don’t have the same interest in what the billboard 40 miles outside the town says about my kale shop, okay? There’s your difference. And the grandfather is because we love grandfathers, okay? There we are. And that’s historic–and go back to the year two, you’ll discover those kinds of distinctions.”

Breyer went on to note that several federal laws on the books are also content-based but haven’t been struck down by the court.

“Content-based?” the justice asked out loud, rejecting the notion that content-based rules are prima facie unconstitutional.

“Hey, the whole [Securities and Exchange Act] is content-based,” Breyer continued. “And what about the infinite number of FDA rules that say you better disclose how much sodium there is? That’s not content? Sodium? It isn’t, it’s salt. But salt, by the way, is a kind of content. And it isn’t good for you.”

Breyer’s point, in the end, being that a strict scrutiny analysis should not, in a dispositive sense, hinge upon whether or not a speech regulation is actually content-based or not.

The Supreme Court itself, however, has largely rejected the justice’s view over the course of its First Amendment jurisprudence over the years–including his fellow left-of-center jurists on the bench–something Breyer himself acknowledged on Wednesday.

“What do you want to say to me?” he asked Shanmugam. “Say, ‘just get on the boat, it’s passed, sailed, do your best?'”

Oral arguments on Wednesday were not the first time the Supreme Court was abuzz with justices talking about kale.

In 2017, Breyer’s late colleague Ruth Bader Ginsberg was memorably asked by a student about eating more kale as a path to longevity. Asked by the student whom the justice wanted to eat more kale, Ginsburg one-lined: “Justice [Anthony] Kennedy,” according to CNN.

Some months earlier, the Washington Post quoted one of Ginsberg’s well-wishers hoping to prolong her tenure on the bench by reportedly pressing: “Can she eat more kale?”

Ginsberg died roughly three years later at the age of 87.

[image via Win McNamee/Getty Images]