Michael Nance. (Image via a Georgia Department of Corrections Mugshot.)

Death row inmate Michael Nance wants the state of Georgia to shoot him to death instead of executing him via lethal injection. On Thursday, the U.S. Supreme Court signed off on allowing the inmate to litigate that veritable last request.

Stylized as Nance v. Ward, the underlying dispute is less about the merits of the case than the procedural way in which the inmate chose to litigate what the court termed his “method-of-execution claim.”

Nance has a unique medical condition that would render his death by lethal injection a likely wellspring of torture. So, he filed an injunction under a federal Civil Rights statute seeking to bar the Peach State from killing him via a needle. His legal theory was that, as applied to him only, the Eight Amendment would bar such likely torture.

Lower courts rejected his efforts for various reasons. Relevant here, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 11th Circuit basically accused the condemned man of playing games with his litigation. A divided three-judge panel said his §1983 claim wasn’t really a §1983 claim at all; rather, the court suggested it was a disguised second attempt to have his death sentence tossed because Georgia currently only executes people via lethal injection.

That two-judge majority held, despite the obvious procedural posture, that Nance was trying to file a second habeas corpus petition; he previously filed a petition to set aside his death sentence altogether and lost. Federal law generally bars successive habeas petitions.

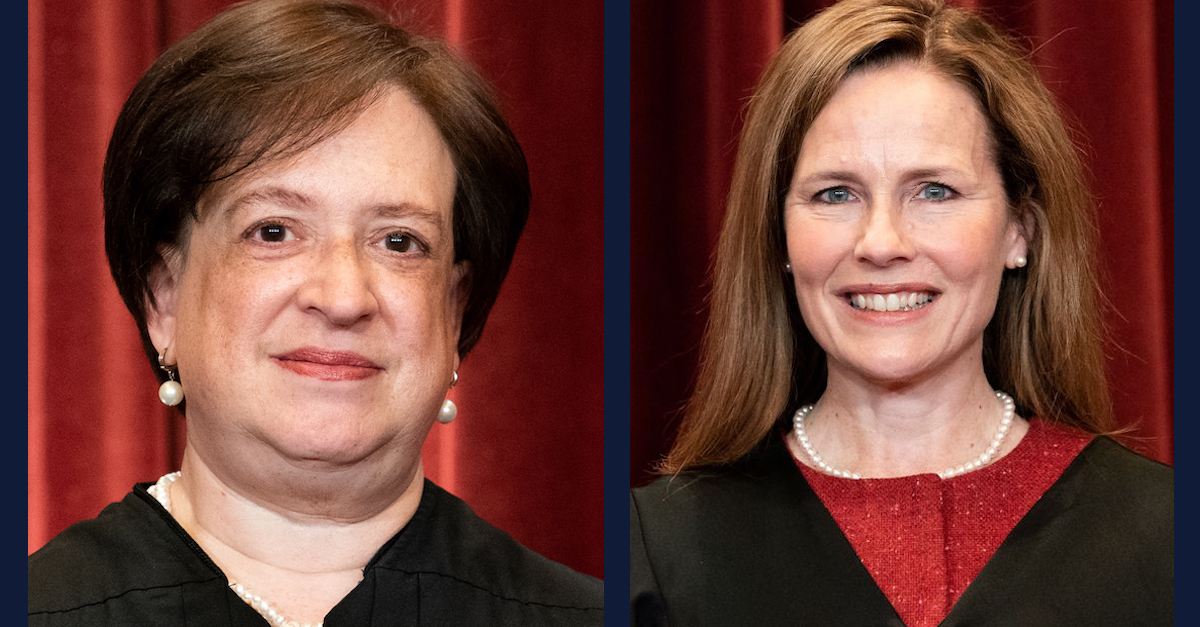

Elena Kagan (L) and Amy Coney Barrett (R). (Images via Erin Schaff/Pool/AFP/Getty Images.)

The 5-4 majority opinion by Justice Elena Kagan sluiced away the procedural morass by noting that Nance actually and factually did sue Georgia’s death penalty apparatus under the auspices of a §1983 claim. The appellate court’s “reconstruction” of Nance’s claim into a habeas petition was simply “unjustified,” a bare majority of justices held.

Kagan explained why this is even a question at all:

This Court has often considered, when evaluating state prisoners’ constitutional claims, the dividing line between §1983 and the federal habeas statute. Each law enables a prisoner to complain of “unconstitutional treatment at the hands of state officials.”

But that’s about it for similarities, the majority held, finding that the overarching interrogatory for the court has been “whether a claim challenges the validity of a conviction or sentence” and therefore falls under habeas relief. Oppositely, the opinion notes, “a prison-conditions claim may be brought as a §1983 suit.”

Kagan then notes two prior Supreme Court cases that have dispensed with method-of-execution claims via §1983:

A claim should go to habeas, the Court held, only if granting the prisoner relief “would necessarily prevent [the State] from carrying out its execution.” In neither case would it have done so. Each prisoner had asked only for a change in implementing the death penalty, and an order granting that relief would not prevent the State from executing him. So the claims could proceed under §1983.

From there, the analysis is straightforward enough due to Supreme Court precedent on how inmates choose to die, if they must die.

“We have held that such a claim can go forward under 42 U.S.C. §1983, rather than in habeas, when the alternative method proposed is already authorized under state law,” Kagan notes. “Here, the prisoner has identified an alternative method that is not so authorized.”

The lack of present-day authorization is where the dissent penned by Justice Amy Coney Barrett takes the most umbrage – because Georgia doesn’t currently authorize death by firing squad.

Barrett argues [emphasis in original]:

The Court is looking too far down the road. In my view, the consequence of the relief that a prisoner seeks depends on state law as it currently exists. And under existing state law, there is no question that Nance’s challenge necessarily implies the invalidity of his lethal injection sentence: He seeks to prevent the State from executing him in the only way it lawfully can.

The majority brushes off those concerns by framing their ruling as part of the parry-thrust tradition between courts and legislatures – Eighth Amendment jurisprudence in particular has long been used to force changes in state law – and this is ultimately, the court held, a minor extension of that standard. Kagan also notes that at least four states already authorize firing squads and other methods of execution that don’t involve the use of needles and drugs.

“The substance of the claim, now more than ever, thus points toward §1983,” Kagan says. “The prisoner is not challenging the death sentence itself; he is taking the validity of that sentence as a given. And he is providing the State with a veritable blueprint for carrying the death sentence out.”

The upshot is the state may have to change its law to shoot Nance to death — but that isn’t what comes next. According to the Supreme Court, Nance can indeed sue under §1983, and the case is remanded to make sure he timely files that document. The litigation from here on out may allow prisoners to use §1983 as a viable way to force states to change their killing methods.