Standing doctrine giveth, standing doctrine taketh away.

The U.S. Supreme Court on Thursday upheld the Affordable Care Act on the basis that Texas and several other states lacked standing to file a 2018 lawsuit challenging the individual mandate as unenforceable and therefore necessitating the wholesale destruction of Obamacare on the basis of an unforgiving severability analysis.

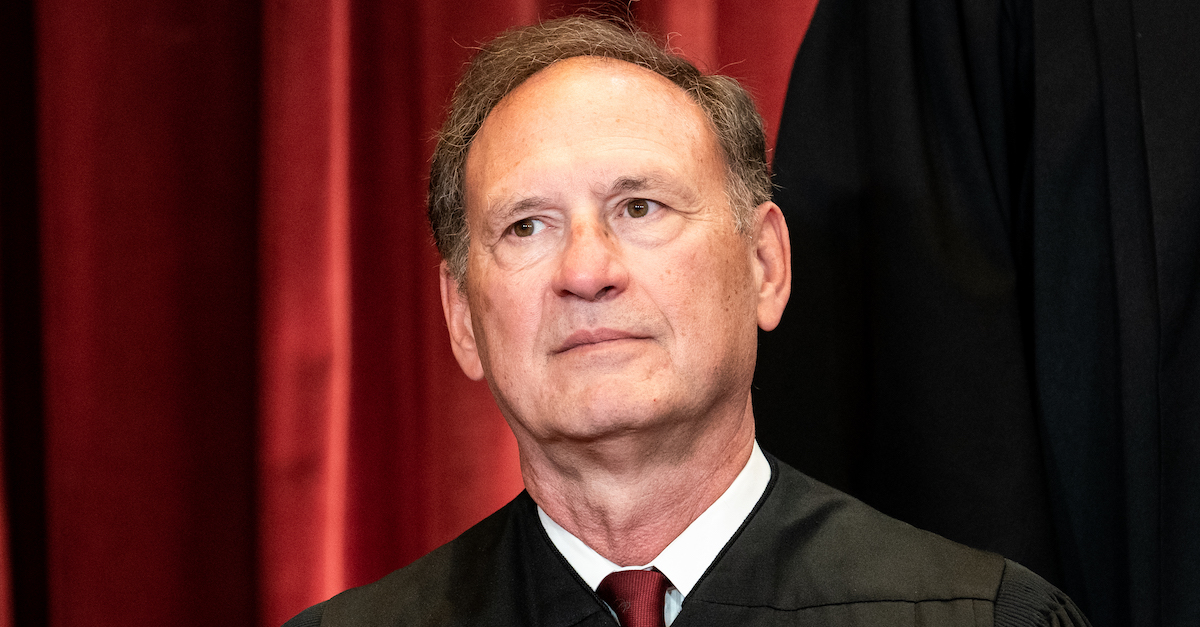

In a lengthy dissent exactly twice as many pages long as the comparatively brief and tidy majority opinion, conservative Justice Samuel Alito — joined by Justice Neil Gorsuch — said that his peers have essentially ignored decades of precedent to issue a “remarkable” and “contrary” holding that is “based on a fundamental distortion of our standing jurisprudence.”

“The States have clearly shown that they suffer concrete and particularized financial injuries that are traceable to conduct of the Federal Government,” the dissent argues, endorsing a liberal interpretation of standing. “The ACA saddles them with expensive and burdensome obligations, and those obligations are enforced by the Federal Government. That is sufficient to establish standing.”

Not so, says the majority.

“Unsurprisingly, the States have not demonstrated that an unenforceable mandate will cause their residents to enroll in valuable benefits programs that they would otherwise forgo,” liberal Justice Stephen Breyer writes. “It would require far stronger evidence than the States have offered here to support their counterintuitive theory of standing, which rests on a ‘highly attenuated chain of possibilities.'”

The majority’s basic premise is that the unenforceable mandate cannot be traced to “an injury in fact” unless several leaps are made from the law to the alleged injury. This is a basic application of standing doctrine as it has existed for quite a while.

To understand the basis of Alito’s gripe, history is instructive.

Modern jurisprudence on Article III standing is widely understood by legal scholars as “conservative standing doctrine,” a judicial theory created by judges in the 1920s who sought to restrain the use and limits of constitutional redress. In other words, standing doctrine was knitted together by judges in order to keep individuals from suing the government over perceived violations of their rights.

Courts in the United States, the nation’s high court in particular, have since used the modern standing framework to skirt the merits of lawsuits time and time again–and often in highly influential and hot-button cases.

More often than not, the standing doctrine has been used to great effect by the institutionally conservative Supreme Court.

Except for the short-lived interregnum from 1953 to 1969 under the leadership of then-Chief Justice Earl Warren, standing doctrine has mostly been used in order to reach politically conservative ends, especially during the Warren Burger and William Rehnquist-led courts that immediately followed that last liberal majority.

This is not a controversial understanding of how the standing doctrine has worked in practice–except, apparently, to Justice Alito.

“If Article III standing required a showing that the plaintiff’s alleged injury is traceable to (i.e., in some way caused by) an unconstitutional provision, then whenever a claim of unconstitutionality was ultimately held to lack legal merit—even after a full trial—the consequence would be that the court lacked jurisdiction to entertain the suit in the first place,” the dissent notes, explaining precisely how standing doctrine actually has operated in practice for decades.

Alito immediately followed that sentence with another that papered over the history of how standing has long been used by the court to foreclose merits discussions.

“That would be absurd, and this Court has long resisted efforts to transform ordinary merits questions into threshold jurisdictional questions by jamming them into the standing inquiry,” the dissent argued, before providing a list of cases where the court made pains to explicitly divorce standing inquiries from merits-based inquiries.

The heart of Alito’s complaint is in Section II-B of his dissent where he upbraids the majority for selectively quoting a prior case in order to, in his opinion, transmogrify the high court’s understanding of its longstanding standing jurisprudence into something else entirely.

From the dissent, at length [emphasis in original]:

The Court’s primary argument rests on a patent distortion of the traceability prong of our established test for standing. Partially quoting a line in Allen, the Court demands a showing that the “Government’s conduct in question is . . .‘fairly traceable’ to enforcement of the ‘allegedly unlawful’ provision of which the plaintiffs complain— §5000A(a).” This is a flat-out misstatement of the law and what the Court wrote in Allen. What Allen actually requires is a “personal injury fairly traceable to the defendant’s allegedly unlawful conduct.” And what this statement means is that the plaintiff’s “injury” must be traceable to the defendant’s conduct, and that conduct must be “allegedly unlawful.” “Allegedly unlawful” means that the plaintiff must allege that the conduct is unlawful. (The States allege that the challenged enforcement actions are unlawful using a traditional legal argument.) But a plaintiff ’s standing (and thus the court’s Article III jurisdiction) does not require a demonstration that the defendant’s conduct is in fact unlawful. That is a merits issue.

Since the Supreme Court’s ruling in Commonwealth of Massachusetts v. Mellon some 98 years ago, standing doctrine has been used—quite often by Alito’s fellow conservatives—to chip away at procedural and substantial rights by deciding merits inquiries under the guise of procedurally-bound hands. But Alito depicts this trend as something new and distorted.

“The Court’s distortion of the traceability requirement is bad enough in itself, but there is more,” Alito argues. “After imposing an obstacle that the States should not have to surmount to establish standing, the Court turns around and refuses to consider whether the States have cleared that obstacle. It’s as if the Court told the States: ‘In order to bring your case in federal court, you have to pay a filing fee of $100,000, but we will not give you a chance to pay that money.'”

Justice Clarence Thomas took note of the “inconsistent” application of standing to severability questions in his anti-Obamacare concurrence that defended the pro-Obamacare majority from Alito’s broadside attacks. He shrugged off this inconsistency by taking cases one at a time and citing other procedural guardrails.

[image via Erin Schaff-Pool/Getty Images]