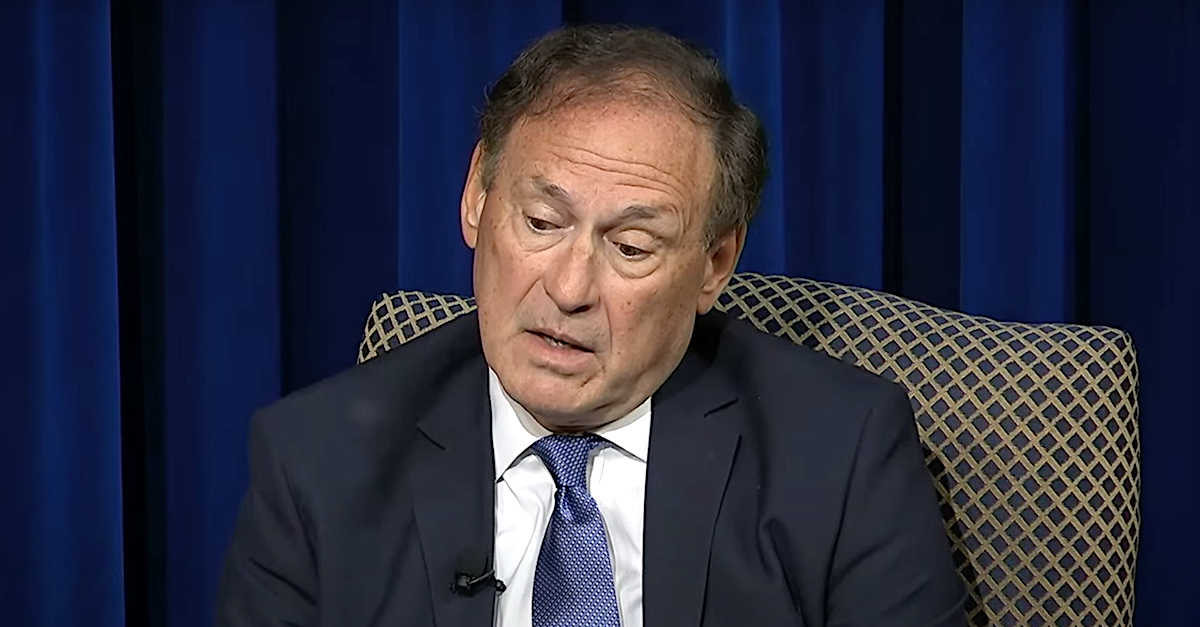

Samuel Alito spoke at a Heritage Foundation function on the evening of Oct. 25, 2022. (Image via YouTube screengrab/The Heritage Foundation.)

The Supreme Court of the United States heard oral arguments Tuesday in a complex federal criminal case that highlights the difference between legal innocence and factual innocence.

The case, Jones v. Hendrix, involves a federal habeas corpus petition filed by federal prisoner Marcus DeAngelo Jones. Jones was convicted in 2000 of possessing a firearm as a felon in violation of 18 U.S.C. § 922(g)(1). Following his conviction, Jones appealed and lost several times. However, in 2019, SCOTUS ruled in Rehaif v. United States that the meaning of 18 U.S.C. § 922(g)(1) is different than it had been interpreted during Jones’ trial.

As a result of the Rehaif ruling, the conduct that led to Jones’ conviction (specifically, that he knew he had a firearm, but was unaware that the gun possession had been illegal at the time) was no longer enough for him to be legally guilty of the crime. Jones challenged his conviction again on the basis that despite no new facts being raised, he did not violate the underlying statute as its meaning has been revised.

Jones lost his bid to overturn his conviction because federal law limits the number of times a prisoner can ask for review of a conviction. Because Jones had already filed a habeas petition years before the Court ruled in Rehaif, he lost his case both before the district court and the United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit.

In a practical sense, Jones’ case seems maddeningly illogical. The 8th Circuit ruled against Jones on the basis that he should have raised his claim in his first habeas petition — but if he had raised the claim at that time, he’d have surely lost, because the Rehaif ruling had not yet happened.

Before the justices are three distinct points of view: (1) Jones’ argument that his conviction should be vacated because he is no longer legally guilty under the current interpretation of the relevant statute; (2) the federal government’s position that Jones should lose for reasons other than those relied upon by the Eighth Circuit; and (3) the Eighth Circuit’s position as argued by Morgan Ratner, a court-appointed amicus curiae and former clerk to both Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Brett Kavanaugh.

Unlike Monday’s oral arguments in which all the justices asked hours of wide-ranging questions, the justices primarily confined their inquiries to matters of statutory interpretation.

At times, some of the justices mentioned the question of whether Jones’ legal innocence under the revised statutory interpretation raises questions of underlying fairness and justice. However, most of the discussion was relegated to whether federal rules actually foreclose the relief Jones seeks. The rules in question surround whether a prisoner may file successive habeas petitions.

Questions from the bench headed in another direction when Justice Samuel Alito queried Deputy Solicitor General Eric Feigin, who argued on behalf of the Department of Justice. Alito focused his colloquy on a practical concern — but not the matter of whether fairness would demand that a legally innocent man be given the chance to challenge his imprisonment.

Rather, Alito raised concerns about what a ruling — even one against Jones — might mean for the workload of the federal courts.

“Do you have any concern about the complexity of the rule that you are advocating?” Alito asked Feigin.

The justice then continued:

Are you concerned that every federal prisoner who wants to bring a successive motion is going to claim that this falls within the traditional scope of habeas, and this would be an escape clause that would be invoked again and again and again, and all the district judges are going to have to analyze the traditional scope of habeas to see whether the claim actually falls within that?

Feigin responded that he was not concerned with overburdening the federal courts because, in his view, it is rare that a case would fall within the narrow parameters suggested by his position in Jones’ case. Feigin told Alito that Jones’ case constitutes “probably a category of one” in which “somebody is in prison for something that Congress never made a crime.”

The judiciary is generally loathe to deal with the usual tidal wave of cases from convicted prisoners who seek to be freed. Most applications are rubbished — but not without time and attention from clerks and judges. Alito’s comments touched on the procedures and the personnel necessary to deal with such matters should the floodgates be opened: courts, after all, have to realistically employ the requisite resources necessary to manage such situations. And, indeed, Alito joined Justice Elena Kagan in 2019 before the House Appropriations Committee to discuss the court’s budget — perhaps why these administrative questions are on his mind. However, Feigin suggested that an avalanche of paperwork from prisoners who want to be freed is unlikely to result from a decision in Jones’ favor.

[Image via Erin Schaff-Pool/Getty Images]