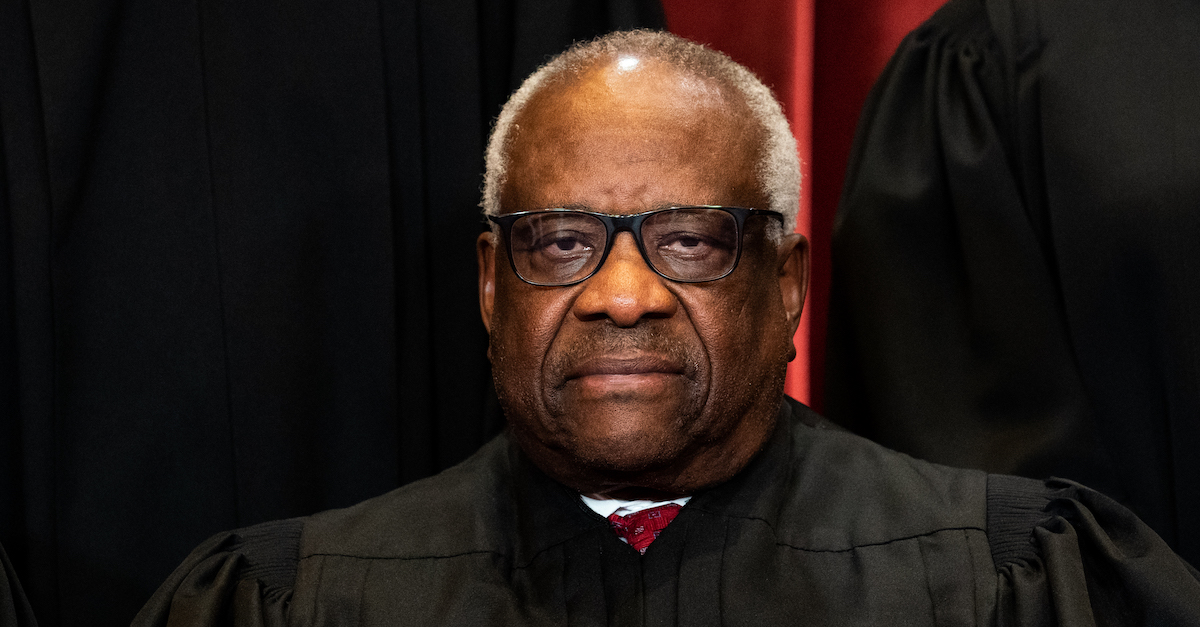

Associate Justice Clarence Thomas.

Justice Clarence Thomas on Monday waged yet another head-on attack on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, penning a furious dissent over the Supreme Court’s refusal to reconsider Shoop v. Cunningham.

Justices Samuel Alito and Neil Gorsuch joined Thomas’ dissent, which slammed the 6th Circuit for its repeated refusal to follow the rules of a federal statute governing habeas corpus petitions.

Jeronique Cunningham was convicted of armed robbery and capital murder and sentenced to death by an Ohio jury in 2002. Cunningham had been involved in a drug deal turned violent, and fatally shot 3-year-old girl, Jala Grant and 17-year-old Leneshia Williams. Cunningham also shot and injured six others.

After his conviction, Cunningham filed a claim for federal habeas corpus relief on the basis that he had been deprived of due process because of juror’s bias against him.

The jury foreperson, Nichole Mikesell, received information about Cunningham from her colleagues at the county’s children-services agency. Mikesell was a child-abuse investigator for the agency who worked regularly with local law enforcement. However, during the voir dire process, Mikesell answered that she had no trouble being impartial and she did not disclose any personal connection to the case.

When Cunningham appealed his conviction, it came to light that Mikesell had been told by colleagues that they were afraid of Cunningham, and that Mikesell herself believed Cunningham to be “evil” and have “no redeeming qualities.” The precise timing of Mikesell’s receipt of background information — specifically, whether Mikesell had heard the comments from coworkers before or after Cunningham’s trial — was not determined during the appeal investigation.

Additionally, the defense investigation related to the appeal revealed that two jurors said they remembered Mikesell saying she knew the families of Cunningham’s victims, and maintained a relationship with them through her employment.

Cunningham filed a habeas corpus claim in which he alleged juror bias based on Mikesell’s information about Cunningham and her relationship with the victims’ families. The district court denied his claim, but the 6th Circuit reversed. Specifically, the appellate court ruled that any “colorable claim” of outside influence entitles a defendant to an evidentiary hearing on the issue of juror bias.

The state appealed, and because SCOTUS denied certiorari, the 6th Circuit’s ruling will stand.

Generally, under the federal Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act (AEDPA), courts are prohibited from granting habeas relief to state prisoners, unless the underlying state ruling was based on “an unreasonable application of, clearly established Federal law, as determined by the Supreme Court of the United States.”

In his dissent to the denial of certiorari, Thomas argued that Cunningham’s habeas claim was not such a case that demanded further review.

“Cunningham merely alleged that outside contact had occurred, based on a speculative reading of an ambiguous postverdict statement,” said Thomas. When the 6th circuit ordered that Cunningham had the right to a hearing, said Thomas, it usurped discretion to which it was not entitled.

The appellate ruling “shows profound disrespect, not merely to the State, but to citizens who perform the difficult duty of serving on capital juries, to the surviving victims of Cunningham’s atrocious crimes, to the memories of the two young girls whose lives he snuffed out, and to their families who still, two decades later, have no assurance that justice will ever be done,” said Thomas.

“Worse and more importantly,” wrote Thomas, “any evidentiary hearing on Cunningham’s family-relationship claim would be an abuse of discretion no matter what court ordered it.” He continued, “The entire factual basis for this claim consists of the foreperson’s statements in the jury room as recalled in two other jurors’ years-later testimony.”

Thomas lamented the injustice sure to come as a result of the 6th Circuit’s ruling:”[jurors’] every word will be picked apart in the hunt for further excuses to drag out this 16-year-old federal habeas action.”

The justice continued with harsh words for the Circuit Court and its impact on Cunningham’s victims:

The 6th circuit’s decision is more than an error—it is an injustice. It shows profound disrespect, not merely to the State, but to citizens who perform the difficult duty of serving on capital juries, to the surviving victims of Cunningham’s atrocious crimes, to the memories of the two young girls whose lives he snuffed out, and to their families who still, two decades later, have no assurance that justice will ever be done.

Thomas also pointed a finger at his fellow justices, remarking, “I disagree with the Court’s newfound tolerance for recidivism,” but qualifying that regardless of SCOTUS’ errors, “primary responsibility for the Sixth Circuit’s errors rests with the Sixth Circuit.”

“That court’s record of ‘plain and repetitive’ AEDPA error, is an insult to Congress and a disservice to the people of Michigan, Ohio, Kentucky, and Tennessee,” he added.

Thomas wrote that the 6th Circuit’s ruling not only “denies society the right to punish some admitted offenders,” but also “intrudes on state sovereignty,” and called the ruling an example of “overt defiance” of SCOTUS’ past precedent.

Thomas even went a step farther and called out (though did not name) specific judges for their erroneous rulings.

“[C]ertain circuit judges’ ‘taste for disregarding AEDPA,’ has found its natural complement in other judges’ distaste for correcting errors en banc, no matter how blatant, repetitive, or corrosive of circuit law,” wrote Thomas, who pointed to the “depressing regularity” with which cases like Cunningham’s reach SCOTUS.

Thomas’ disdain for the 6th Circuit’s handling of AEDPA claims is nothing new. In June, Thomas penned another lengthy dissent in which he said that the 6th Circuit has made almost two dozen AEDPA-related errors in the last two decades.

[Image via Erin Schaff/Pool/Getty Images]