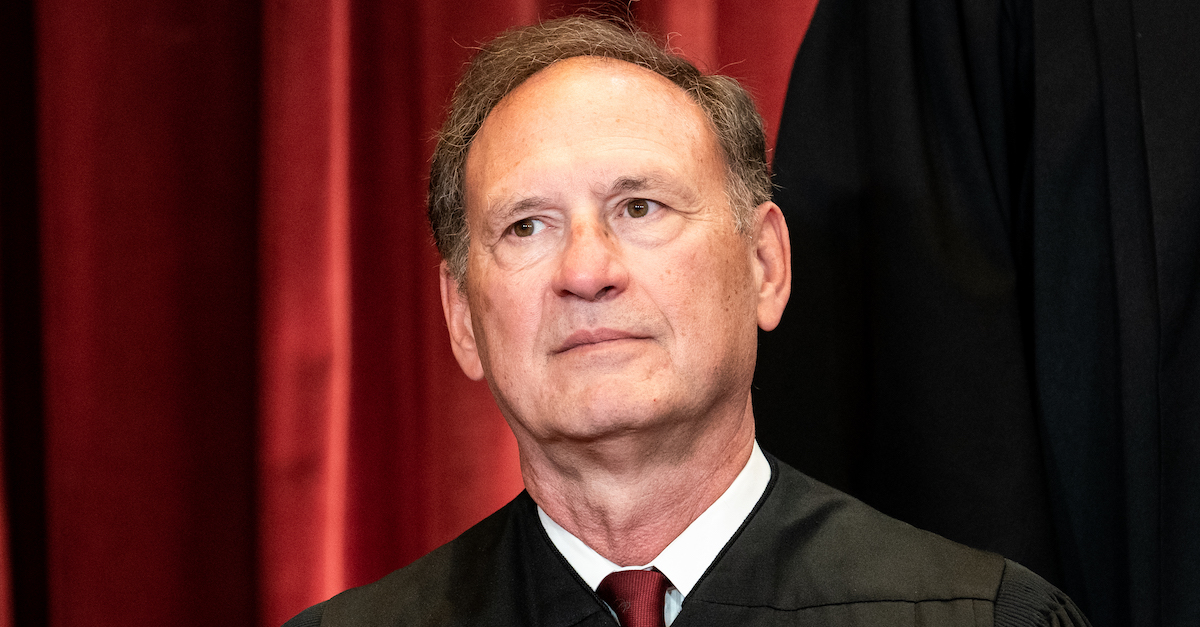

Associate Justice Samuel Alito

The Supreme Court of the United States declined to hear an appeal from the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts in a case asking whether religious colleges are entitled to use the “ministerial exception” to avoid requirements of federal employment law. Though the denial means a near-term loss for the religious college, a statement joined by four of the court’s conservative justices leaves little doubt that there is strong support within SCOTUS for the school’s position that its professors should indeed be considered “ministers.”

Justices Clarence Thomas, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett agreed in the decision to deny certiorari by joining Justice Samuel Alito’s six-page statement on the decision. The statement qualified: “But in an appropriate future case, this Court may be required to resolve this important question of religious liberty.”

The case, Gordon College v. DeWeese-Boyd, arose when Gordon College (a Christian college in Wenham, Massachusetts) declined to promote Margaret DeWeese-Boyd to the rank of full professor. DeWeese-Boyd sued the school, claiming that the college’s decision had been based on “her vocal opposition to [the college’s] policies and practices regarding individuals who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer.” The trial court ruled in favor of DeWeese-Boyd, denying the college’s claim that it was entitled to use the “ministerial exception” to shield itself from potential liability. On a direct appeal, the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts affirmed.

In his statement, Alito summarized the state court ruling: “Though the court recognized that she was required to ‘integrate the Christian faith into her teaching, scholarship, and advising,’ the court reasoned that this integrated teaching was ‘different in kind’ from religious instruction.”

Despite the Court’s current refusal to review the case, Alito had some critical words for the Massachusetts court. Referencing the court’s basis for its ruling — that DeWeese-Boyd was not a “minister” because she did not directly teach religion — Alito wrote, “That conclusion reflects a troubling and narrow view of religious education. What many faiths conceive of as ‘religious education’ includes much more than instruction in explicitly religious doctrine or theology.”

The justice went on to provide some examples:

For example, a professor teaching a course on the civil rights movement at a secular college might concentrate on the political, economic, and sociological aspects of the struggle for racial justice, while a professor at a Christian college might also highlight Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s faith and the biblical arguments in his famous Letter from Birmingham Jail. Similarly, an English professor at a secular college might see nihilism and skepticism in Shakespeare’s King Lear, while a professor at a Catholic school might present it as a pilgrimage to redemption.

Although the justices clarified that they “have doubts about the state court’s understanding of religious education,” they chose to deny review now based on the timing of the appeal. Because the lower court’s ruling was not a “final judgment” on the matter, the case is essentially not ready for SCOTUS review.

The Gordon College case comes not long after SCOTUS’s July 2020 ruling in Morrissey-Berru v. Our Lady of Guadalupe. Alito, writing for a 7-2 majority, found that the First Amendment protected a grade-school’s right to hire and fire teachers without adherence to anti-discrimination laws, because teachers should be considered “ministers.” Dissenting Justices Sonia Sotomayor and the late Ruth Bader Ginsburg characterized the Morrissey-Berru ruling as one that “stretches the law and logic past their breaking points.”

[image via Erin Schaff-Pool/Getty Images]