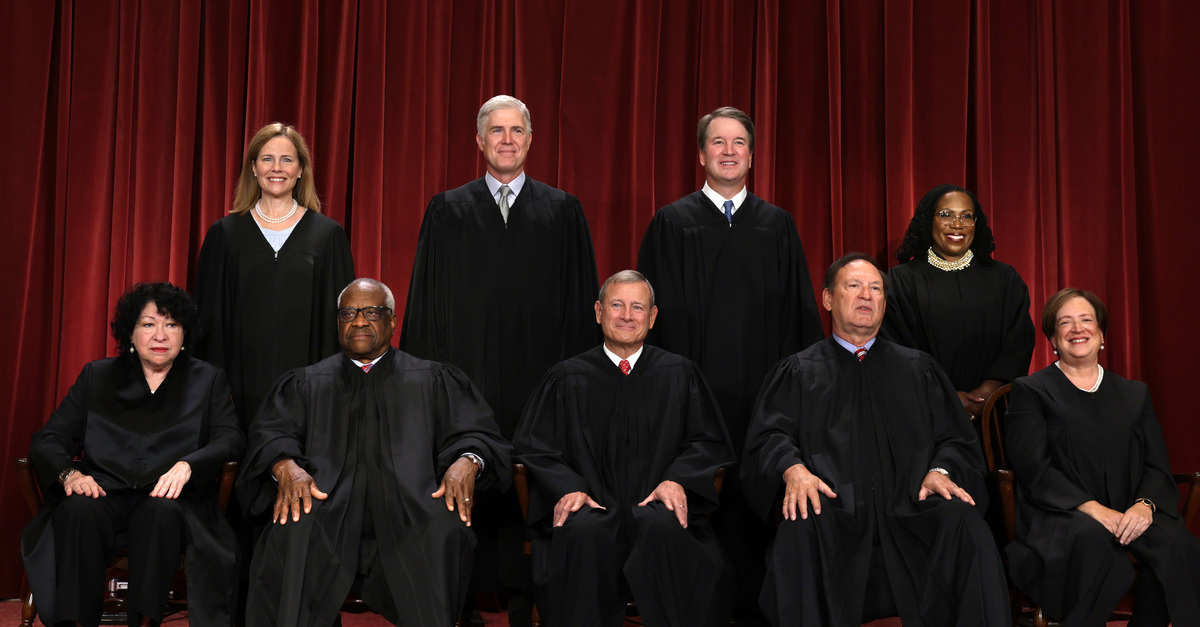

United States Supreme Court (front row L-R) Associate Justice Sonia Sotomayor, Associate Justice Clarence Thomas, Chief Justice of the United States John Roberts, Associate Justice Samuel Alito, and Associate Justice Elena Kagan, (back row L-R) Associate Justice Amy Coney Barrett, Associate Justice Neil Gorsuch, Associate Justice Brett Kavanaugh and Associate Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson.

The justices were jovial as they heard oral arguments Wednesday in Wilkins v. United States, a dispute with underlying facts befitting an episode of Yellowstone: Montana landowners suing the federal government for land-locking them with an improper easement. At stake, though, is not the justices’ views on the Western wilderness, but rather, whether the federal government’s 12-year limitation on lawsuits applies to the landowners even when recent SCOTUS rulings in other cases might indicate otherwise.

Larry Steven “Wil” Wilkins (a veteran who lives with post-traumatic stress disorder) and his neighbor Jane Stanton (a widow who lives across Robbins Gulch Road from Wilkins) granted an easement to the U.S. Forest Service in 1962. Under the terms of the easement, the federal government was permitted to maintain a road across privately-owned land. The easement functioned without major incident until 2006, when the Forest Service put up a sign that read “public access thru private lands.”

Wilkins and Stanton said that since the sign was posted, there’s been all manner of problems on the road. They claim to “have had to deal with trespassers on their private property, theft of their personal property, people shooting at their houses, people hunting both on and off the easement, and people travelling [sic] at dangerous speeds,” — and once, the shooting of Wilkins’ cat by a passing traveler.

Frequent use of the easement has also caused land erosion, which in turn resulted in sediment build-up on neighboring properties; those properties then suffered “washout,” which is a serious concern for future use of the land. Meanwhile, the claimants contend that the Forest Service has done less and less to maintain its easement, despite their many requests for assistance.

Wilkins and Stanton eventually sued, and the dispute before the justices Wednesday relates to the timing of that lawsuit. The lower court said, and the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit agreed, that the plaintiffs’ lawsuit was too late as it had been filed after the 12-year statute of limitations had run.

The relevant statute is the federal Quiet Title Act, which allows litigants 12 years within which to file their claims. The legal question before the justices is whether that statute of limitations is a “jurisdictional” or a “claims-processing” rule. If the justices say that it is a jurisdictional regulation, then the rule goes to the power of the court to hear the case and the landowners will lose. If, on the other hand, the rule is simply considered a procedural claims-processing rule, Wilkins and Stanton may still have a chance to move ahead with their lawsuit, because the claimants’ lateness could be excused as an equitable remedy.

The appellants’ arguments rely in large part on a 2021 SCOTUS decision in Boechler v. Commissioner in which SCOTUS ruled against the Internal Revenue Service that a 30-day time limit in a tax case was not jurisdictional, and was therefore subject to equitable tolling. The dispute before the justices brings up an important question: should SCOTUS follow a modern trend of its own creation that require “jurisdictional” statutes to reflect their nature within their own wording, or should it stick to older precedents involving the Quiet Title Act in particular?

When the justices heard attorney Jeffrey McCoy’s arguments on behalf of the appellants, they treaded lightly on the idea of substituting their own judgment for that of legislators.

Chief Justice John Roberts at first seemed inclined to side-step the case’s central question entirely. At one point, Roberts questioned McCoy at length, asking why the jurisdiction/claims-processing distinction even matters.

“Either way, you lose,” Roberts told McCoy, explaining “twelve years is twelve years.”

Justice Samuel Alito pressed McCoy on whether he was asking the Court to adopt a “magic words test,” in which the precise language of the statute would automatically dictate the outcome.

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson raised concerns about how a ruling in McCoy’s favor might conflict with past rulings, and called McCoy’s suggested legal framework “a really messy and odd way” of resolving the legal issue at the heart of the case.

Justice Amy Coney Barrett was also concerned about SCOTUS stepping out of its judicial lane by ascribing meaning to a statute that Congress might not have intended.

The chief justice returned to the microphone with a lengthy commentary about the current Supreme Court’s process of interpreting statutes.

“Back in the battle days when we had a statute to interpret, we looked at all sorts of stuff: hearings, reports, testimony, all sorts of things, sometimes to the expense of the actual language,” Roberts began, noting that, “these days, we look at [a statute’s actual language] much more carefully.”

Roberts continued his question, asking about what should happen even outside the context of statutes of limitation. He asked what should be done when the Supreme Court’s modern system of interpretation leads to conflicts with what the high court has done historically:

If we have interpreted the meaning of a statute, and we look at what we did in 1950 — and there, the Court relied on all this extra-statutory material, and today where we have a different approach — are we supposed to go back and say ‘that was then and this is now and now we’re trying to look primarily at the plain language’? Is that what we do?

When Assistant to the Solicitor General Benjamin Snyder took the podium for the federal government and advocated that the justices decide the case by sticking with “settled principle,” Justice Clarence Thomas asked what the statute’s plain-reading might mean.

“Could you reach the same conclusion just reading the statute?” Thomas asked of Snyder’s argument.

When Alito picked up the questioning, he presented a query about how the Supreme Court should interpret its own precedent in deciding the case at hand. Alito’s question contained a deference to stare decisis that stood out against the backdrop of Alito’s recent willingness to disregard long-settled precedent.

“We are often called upon to decide what we in fact held in a prior case, because that’s important for stare decisis purposes,” Alito said.

He then asked Snyder, “Do you think that the test for determining what we held in a prior case, and therefore, what is protected by stare decisis is different in this context?” — referring to the specific legal context of the Quiet Title Act’s statute of limitations.

The question might not be particularly notable coming from another justice. But from Alito, the offhand remark characterizing stare decisis as a concept that stalwartly protects prior rulings was starkly incongruous to his recent actions.

In Alito’s bombshell decision overruling Roe v. Wade last summer, the justice said that stare decisis must sometimes take a backseat to the need for SCOTUS to “correct our own mistake.” Alito went on at length to bolster his argument with examples of now-overturned precedents (such as Plessy v. Ferguson, for one) that were as “erroneous” as Roe had been.

Justice Neil Gorsuch entered the conversation Wednesday when he cautioned the federal government against relying too much on every word contained SCOTUS rulings.

“When we are trying to figure out what we’ve held in a prior case versus what’s extraneous, we’ve often cautioned parties against reading our opinions like statutes and giving talismanic effect to every word,” said Gorsuch.

The Wilkins case is an unusual inclusion on the high court’s docket, as the justices do not often consider the highly local disputes of rural Montanans. However, the case has given the justices the chance to make a broader statement about statutory interpretation, the use of past precedent, and the power of the federal government to set strict rules for the timelines of raising disputes.

You can listen to the full oral arguments here.

[Image via Alex Wong/Getty Images]