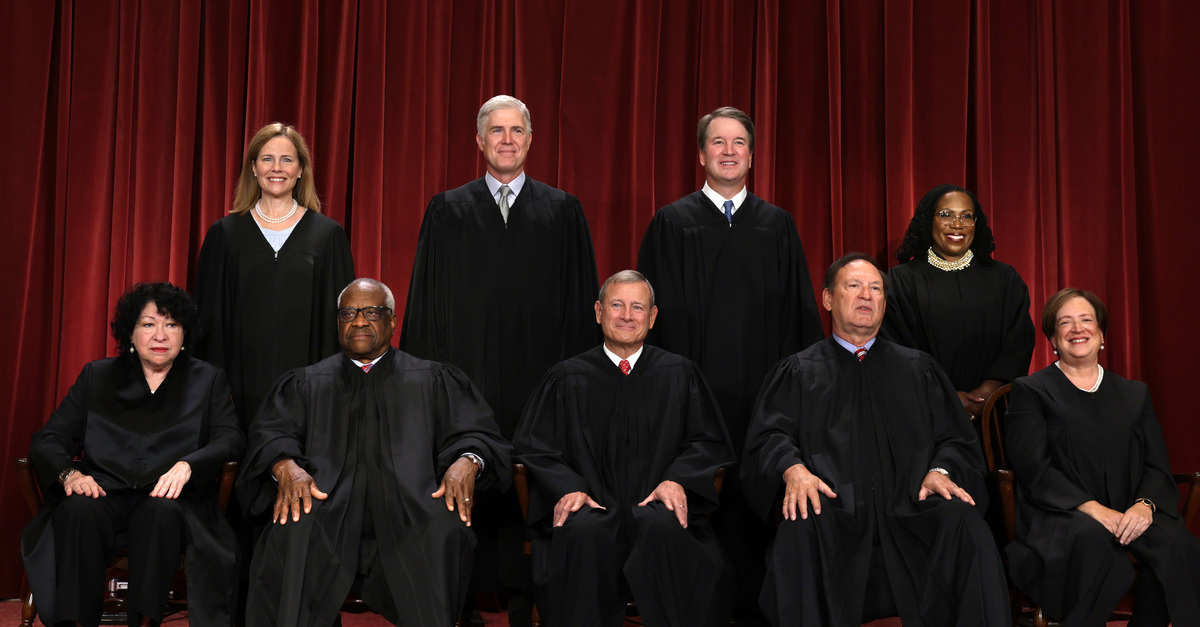

United States Supreme Court (front row L-R) Associate Justice Sonia Sotomayor, Associate Justice Clarence Thomas, Chief Justice of the United States John Roberts, Associate Justice Samuel Alito, and Associate Justice Elena Kagan, (back row L-R) Associate Justice Amy Coney Barrett, Associate Justice Neil Gorsuch, Associate Justice Brett Kavanaugh and Associate Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson pose for their official portrait at the East Conference Room of the Supreme Court building.

A new year of Supreme Court oral arguments kicked off on Monday with In Re Grand Jury, a dispute about the extent to which the attorney-client privilege can allow a law firm to withhold client documents from grand jury subpoenas.

A law firm’s right to keep its communications with clients secret has been a hot-button issue in politically-charged disputes in recent years, particularly involving Trump and his lawyers.

The petitioner firm in question (whose identity is redacted in court documents to protect the secrecy of grand jury proceedings) received a grand jury subpoena for documents related to a criminal investigation of one of its clients. The firm responded by turning over nearly two thousand documents. However, the firm held back other “dual purpose” documents (those documents that related to both legal and non-legal tax-related advice), and argued that they were protected by the attorney-client privilege.

Both the district court and the Ninth Circuit sorted the documents by their “primary purpose”: those that had been made “for the primary purpose” of legal advice would be privileged, but those made primarily for tax preparation would need to be disclosed. The idea of organizing the documents by purpose was nothing new; what is questionable, though, is whether the criteria the lower courts used had been correct.

Other circuits — including, most notably, the D.C. Circuit — have said that when documents have dual purposes, there is no need for a district judge to determine a single primary purpose. Rather, a document might have multiple purposes, and if legal advice is an important one among several, that document would be privileged.

When Justice Brett Kavanaugh was a judge for the D.C. Circuit, he wrote an opinion about this issue, in which he ruled that a dual-purpose communication could remain privileged as long as legal advice represents a “significant” purpose. If Kavanaugh’s fellow justices adopt his methodology moving forward, it would mean far more documents are shielded from discovery based on attorney-client privilege, as many communications might provide “significant” legal advice even when they were drafted primarily for offering tax (or other) advice.

Attorney Daniel B. Levin faced a bench that seemed skeptical about expanding the scope of the privilege as he argued the case on behalf of the law firm.

Justice Elena Kagan called Levin’s proposed use of the “significant purpose” test “a big ask” that does not comport with the underlying purpose of the attorney-client privilege. Kagan then jokingly asked Levin how his argument would square with the “ancient principle of ‘if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.'”

Justice Clarence Thomas raised a question that Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson later repeated: What would happen when a lawyer adds something to a communication that is “admittedly significant, but admittedly subsidiary”?

Thomas pressed Levin on whether there would be any role a lawyer could play in a communication that would be deemed minor enough to exclude that communication from the attorney-client privilege.

Jackson summarized the broad definition of privilege suggested by Levin’s argument, “You say as long as it’s a legitimate point, that’s good enough to require that the entire thing would be privileged.”

Jackson remarked that district courts are “not doing math,” but are rather, “just looking at a decision that could go either way and then making a judgment.”

Assistant to the Solicitor General Masha Hansford talked about the potential consequences of the Court’s expansion of the attorney-client privilege.

Hansford said that adopting the “significant purpose” test would mean that adding any legal element to a communication — even one that is only a pretext — could be used to “allow anyone to buy their way into the privilege.” Litigants could simply hire a lawyer to review all communications and thereby have everything covered by attorney-client privilege, she warned.

Chief Justice John Roberts pressed Hansford on the practicality of courts continuing to use the “primary purpose” test. Roberts said that it was “putting a lot on the judge” to decide whether one of three different issues in a hypothetical memo is “the big one” for purposes of determining whether the document must be disclosed.

When the discussion between Hansford and the justices began to explore how district courts typically make determinations relating to privilege, Justice Neil Gorsuch remarked that Hansford’s argument sounded like it was centering more on the “significant purpose” test rather than the “primary purpose” test for which the government advocated in its brief to the Court.

Kagan threw out a softball question and asked Hansford, “What is the danger of going to the “significant” test and making all those communications privileged?”

Hansford responded by articulating just what is at stake in the case.

“Most business communications have one eye on legal implications,” she said, explaining that whether communications relate to clinical trials for drug data or simulation results for new cars, a lawyer might well take part in drafting documents, potentially rendering them undiscoverable if they are deemed privileged.

“So all of that would be covered, wouldn’t it?” pointed out Kagan, indicating an unwillingness to stretch the attorney-client privilege to such a wide range of business communications.

[image via Alex Wong/Getty Images]