The U.S. Supreme Court on Thursday limited the scope of the 1965 Voting Rights Act (VRA) in an opinion that broke down along standard ideological lines. In a separate yet terse concurrence, Justice Neil Gorsuch set the stage for the further evisceration of the nation’s marquee voter protection law.

In two consolidated cases stylized as Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee, the high court ruled that two Arizona voting restrictions do not run afoul of Section 2 of the VRA because they were not specifically authored with racist intentions against non-white voters.

University of California Irvine Law Professor and election law expert Rick Hasen explains how the section works in practice and in light of recent efforts by the nation’s high court to limit the VRA:

With the Supreme Court effectively killing Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act in 2013 in Shelby County v. Holder, Section 2 remains one of the strongest voting rights tools in the United States. Section 5 targeted jurisdictions with a history of racial discrimination in voting and required them to get federal approval before making changes in voting laws. This preclearance required jurisdictions to demonstrate that their proposed changes would not make minority voters worse off. Section 2, as amended in 1982, uses a different standard that applies nationally. It puts the burden on voters to show that a law prevents protected minority voters from equally participating in the political process and electing representatives of their choice.

In other words, Section 2 (until Thursday) was a fairly thoroughgoing statutory method for individual voters to avail themselves of the franchise by bringing individual (or class action) lawsuits against racist voting laws. Justice Samuel Alito‘s majority opinion severely claws back the potential of such lawsuits to find violations without proof of actual racism in the passage of such laws.

However, in his concurrence, Gorsuch would eviscerate the right of voters to sue altogether.

“I join the Court’s opinion in full, but flag one thing it does not decide,” the conservative jurist notes. “Our cases have assumed—without deciding— that the Voting Rights Act of 1965 furnishes an implied cause of action under §2. Lower courts have treated this as an open question. Because no party argues that the plaintiffs lack a cause of action here, and because the existence (or not) of a cause of action does not go to a court’s subject-matter jurisdiction, this Court need not and does not address that issue today.”

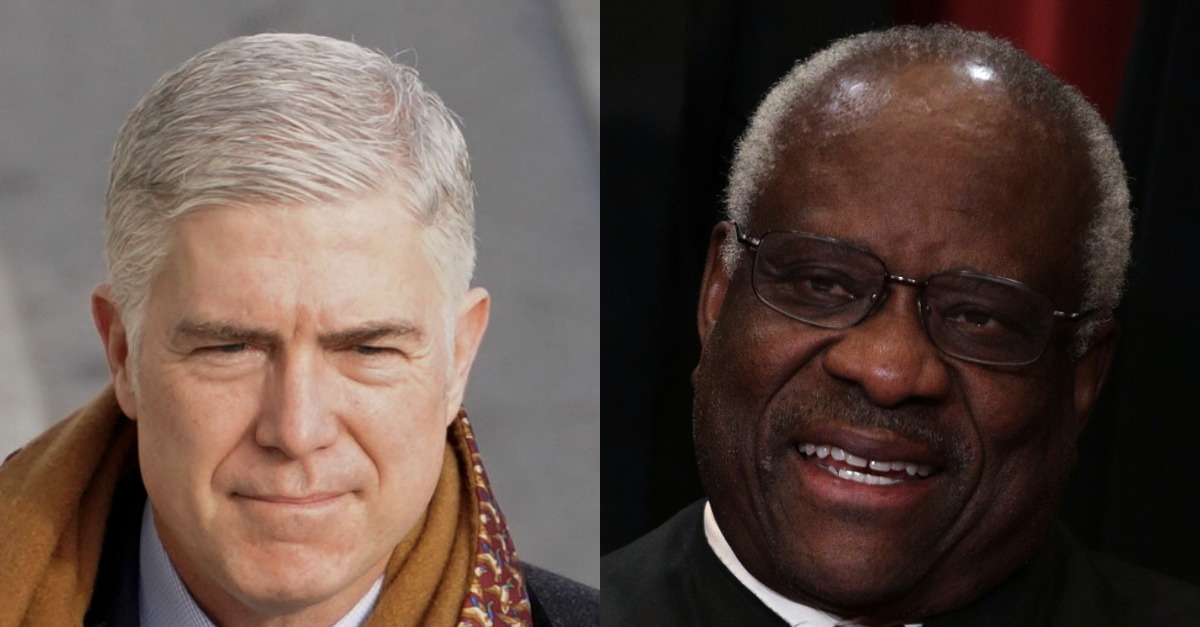

Those words by Gorsuch were joined by Justice Clarence Thomas,

The upshot of that brief bit of dicta was not lost on legal experts.

“Justices Gorsuch [and] Thomas have a brief concurrence reminding everyone that there may not even be a cause of action (a mechanism to sue) under Section 2 — but that’s not at issue in this case,” noted legal reporter Steven Mazie via Twitter. “In other words: there’s still more violence to the VRA that might be done in the future.”

“Classic Gorsuch and Thomas questioning whether Section 2 authorizes a private right of action in their (mercifully, non-majority) concurrence,” tweeted Campaign Legal Center voting rights lawyer Jonathan Diaz.

Legal journalist and attorney Mike Sacks had the same takeaway:

When Congress passes a federal law, they typically have two choices: create a cause of action that allows individuals to sue in order to vindicate their rights or leave it to the courts to decide that the language of a statute is more or less meaningless without an implied private right to sue over such rights violations.

Implied causes of action have been increasingly disfavored by the increasingly conservative Supreme Court since the late 1980s.

The Gorsuch-Thomas concurrence in Brnovich is self-identified as a “flag” for fellow traveler conservatives to bring litigation that questions the implied cause of action in Section 2. When and if that issue is actually heard by the court, its modern jurisprudence suggests the VRA, in large part, may not be long for this earth.

[image via Melina Mara – Pool/Getty Images; Alex Wong/Getty Images]